We did a Design Fiction workshop as a kind of follow on to the Convenience newspaper. Our idea was to take the observation that the trajectory of all great innovations is to asymptotically trend towards the counter of your corner convenience store, grocer, 7-11, gas station, etc. Discerning the details as to why this occurs isn’t our primary concern. It’s an observation that tells some stories about convenience as a cultural aspiration of some sort, broadly; it’s a way of talking about industrialization, capital, the trajectory of “disruptive innovations”; it’s a way of talking about the things we take for granted that we wouldn’t were convenience to go away in some sort of puff of apocalyptic dust; it identifies the net present value of things as 99¢ and buy 1 get 1 free.

But that was the newspaper version that took the things today and made them plain. (You can get a PDF of it here.) It also serves as the conceptual set-up for what we did next which was for Nick Foster and I to tramp to Tempe Arizona to the Emerge event at ASU in order to run a workshop that would take the Corner Convenience as our site to do a bit of Design Fiction gonzo filmmaking. We imagined the Corner Convenience in some Near Future.

A couple of notes about the production of these films, but also the production of Design Fiction films generally. As the genre progresses — and it is progressing like crazy, which is fantastic — and evolves as a way to do design and make things rather than just film them, systems and structures and processes get informally put into place. I’m talking about things like styles and conventions and the visual language of Design Fictions. I’m attentive to these because it becomes useful in a Bruce Block sort of way to make use of the developing visual language and genre conventions.

One thing I notice is the way that now, early on in evolution of Design Fiction, tools have determined, or perhaps over-determined, what gets made to count as Design Fiction. Contemporary visual effects tools and software are incredibly sophisticated at what they do. I think they may have a tendency to over-determine the filmmaking. By that I mean to say that, now that we can do desktop motion capture, planar tracking, and animation in scenes — we end up with Design Fiction of surfaces as screen interfaces as if that’s the future of interaction. Which it might be, but seriously — what else? At the same time, things like green screen which is effectively a drop-down menu item in AfterEffects, or the insertion of CAD rendered objects composited seamlessly into scenes with (almost) drop-down menu item workflows, etc. That’s all a bit of the tool leading the ideas, which is generally disconcerting especially if you don’t realize or take notice of the way an algorithm is determining one’s thinking about what could be.

Don’t get me wrong — they are seductive eyeball candies. The Corning one is particularly enjoyable as pure visual experience. So is that Microsoft Office future fiction film. But these don’t feel real except for the degree of finesse in the visual effects. It almost feels like someone found the tools to do this and then the tools over-determined the diegetic prototyping. The tool was the door knob and then the designers or marketing people or whoever was behind this took the door knob and tried to build a house around it. And, in any case — they are so clean and almost fascistic in their fetish of the slick, glamorous, gleaming and super pricey stuff we’re being told we’ll live with in the near future.

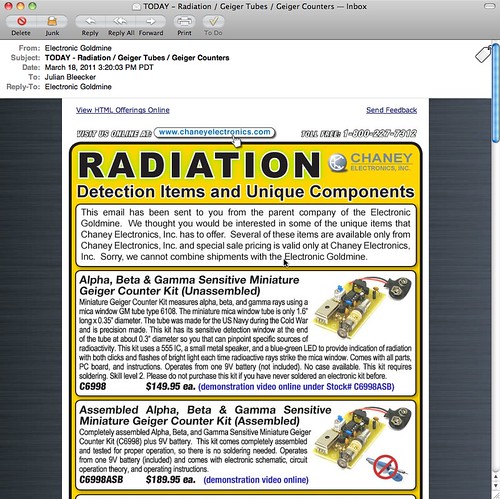

What about the forgotten underbelly of the mundane futures? The ordinary and quotidian. The things that are so tangible as imminent as to be almost ignored. Like the things one would find in the Corner Convenience store but were once fantastic, extraordinary, mind-boggling disruptive stuff.

Using the Corner Convenience as our design fiction site directed us to consider things that were once amazing and are now 99¢ or $1.99 or 3 for 99¢. They’d be available *everywhere, which is as important to consider as some sort of silly ersatz coffee table that has a touch screen built into it. A thing that 1% of the world cares about, or can even comprehend or conjure some half-baked rationale to own and use before it gets tossed out when its planned obsolescence means it won’t show the antique JPEG format anymore without a firmware upgrade that probably won’t upload to it because of some byzantine tech issues that frustrates you to the point of not even caring about the thing anymore. You know? I’m still trying to get my brand new $99 5-star reviewed Brother laser printer (which replaced the 10 year HP I had that just stroked out and died) to run the crappy configuration software so I can use its built-in WiFi features. But, like..I’ll always be able to flick the flint-y scroll of a BiC lighter and make fire.

That was an aspect of the design principles that shaped these three films we made. We were deliberate in designing the production and the things in such a way that they were whiz-bang-y iPhone things with touch screens and surfaces. It was real stuff that would tip into that realm of convenience without missing a beat, and without Wieden+Kennedy running a campaign that seduces the 23-year-old bearded, skinny, waifish, Williamsburg/Brick Lane/SOMA hipsters into bending their knee — again — to the Palace of Apple.

In this Near Future Corner Convenience Store, Snow Leopard is a variety of synthetic meat jerky, not an operating system.

Anyway. Enjoy our three design fiction films.

The Players

John Sadauskas — Ersatz Shoplifter

Julie Akerly — Clerk

Dan Collins — Caffeinated Drunk/Hangover Guy

Joshua Tanenbaum — Panda Jerky Porno Trucker Guy

Background Talent

Nicole Williams

Muharrem Yildirim

Workshop Props & Make Stuff Team

Alex Gino

Joshua Tanenbaum

Adiel Fernandez

John Sadauskas

Nicole Williams

Muharrem Yildirim

Byron Lahey

John Solit

2nd Unit Production

Byron Lahey & John Solit

Thanks To Tops Liquor Staff

Greg Eccles — Owner

Matt Bannon — Manager & Nametag Maker

Special Thanks To

Assegid “Ozzie” Kidane

Directed By Julian Bleecker

Produced By Nick Foster

A *Near Future Laboratory* Production