What was sticking in my mind, and has been recently, and especially after dinner conversation and the lecture which was on Design Fiction with an emphasis on the relationship between props, prototypes, and the normalization/everyday-making of provocative ideas.

A few notes on this point, as reading notes from Latour’s *Reassembling the Social*

Making normal and everyday serves a purpose, I am thinking, in design and in the communication of design ideas.

1. As to the point that it serves the purpose of design, I mean that it brings it into the realm of the familiar, putting something or an experience or a moment into the world and making the engagement *exist* as if it needs no explanation — it is here, and perhaps even it is the case that it is near-obsolete so we can tell a story about its entire life. We defetishize newness and glamour, retreating to the mode of familiar, reliable blandness, as most things go that have lived a full life in the world. If something has not become everyday, chinked on a corner, or experiencing a glitch, or booting a little slowly this time, or making an aged complaint, it has not had a good, long life in the world ((discounting a normative assessment as to what is *good*, or the point that perhaps “it” is new and just crappy and poorly made.)) Which basically suggests it was here for one failed Christmas push and then dropped off the edge of the Earth. Or has just become a cherished relic, or is simply old and worn, but still precious and useful.

2. In the communication, making something everyday is meant to suggest that it has become part of life — perhaps not everywhere, which is not always the goal, nor is ubiquity. But, ‘part of life’ suggests that it’s a good idea and the effect is to communicate as much as this — that it could have been here, around and with us. The communication normalizes the thing to the point of routine blandness. Whether this happens by association or more directly is significant. In the communication, don’t have people smiling with glee when operating/experiencing/discussing the thing, and don’t explain what is going on as if the communication is a features-and-functions list. Didactic and apologetic explanations are a poor substitute for a well-designed thing that expresses itself through a story or fits into everyday life without a list of “whys” or “whats.” Cinematically speaking — *show it, don’t tell it.* Let the communication describe if it needs to — but don’t explain. If you still need to explain something, you need to *explain* in the material — go back and iterate the design. The explanation should be the product of the design, not a way of substituting for an opaque object — the materialization of your ideas in the object/thing/service/widget should effervesce from the communication.

3. Rather than the design tactic of spectacle-making, what about making things normal so that designs move into their place in the world, perhaps even moved off to the utility drawer of the world to become either quaint or so routine and everyday that they are taken for granted. Like a AA battery. No one every made much of a spectacle of those things, except maybe Madison Avenue, once, together with a phalanx of Rabbit troubadours.

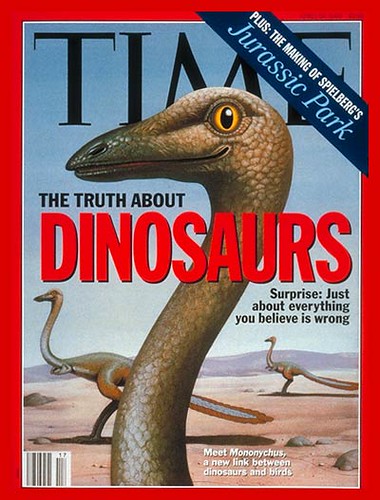

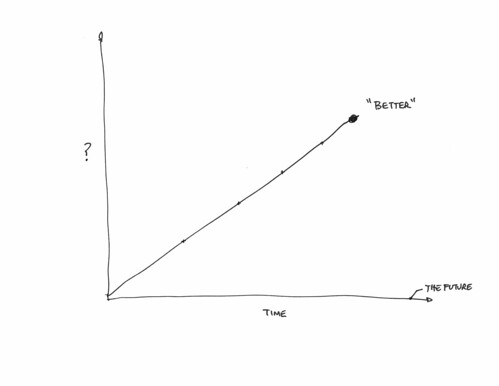

4. I am wondering about implementations and ideas that are two-way props/prototypes. A design tactic that is encouraged to go into the future by materializing new ‘near future worlds’ and then come back into the past, as in an archeological unearthing and investigation and un-constructing of what is around us today. On the one hand, forward-into-the-future design creating new worlds that are hopefully better than the ones we have today. On the other hand, taking what we have today and describing it in the way of sociology-of-associations, anthropology, science studies, &c. Dig something up that once existed and tell its story — or mis-tell it for the purpose of showing how a thing can be re-inscribed with unexpected contexts so as to remind us how significant the interaction and the experience is in making the object meaningful.

So..what? Why this strategy for design and communicating a speculation, or an idea, or something future-fictional?

**To help imagine what things will become and to defetishize the things that are normally elevated beyond themselves — like when new gadgets are oogled and ahhhhgle’d and beyond what they deserve because, ultimately, at some point, it all becomes crap that’s thrown out anyway. (The Near Future Laboratory Defetishization Bureau recently issued a Fatwah on all ‘unpacking’ blog posts and descriptions.)**

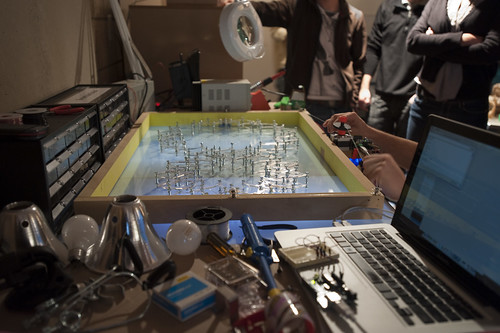

In plain English, to say something is constructed means it’s not a mystery that has popped out of nowhere, or that it has a more humble but also more visible and more interesting origin. Usually the great advantage of visiting construction sites is that they offer an ideal vantage point to witness the connections between humans and non-humans. Once visitors have their feet deep in the mud, they are easily struck by the spectacle of all the participants working hard at the time of their most radical metamorphosis. This is not only true of science but of all the other construction sites, the most obvious being those that are at the source of the metaphor, namely houses and buildings fabricated by architects, masons, city planners, real estate agents, and homeowners. The same is true of artistic practice. The ‘making of’ any enterprise — films, skyscrapers, facts, political meetings, initiation rituals, haute couture, cooking — offers a view that is sufficiently different from the official one. Not only does it lead you backstage and introduce you to the skills and knacks of practitioners, it also provides a rare glimpse of what it is for a thing to emerge out of inexistence by adding to any existing entity its time dimension. Even more important, when you are guided to any construction site you are experiencing the troubling and exhilarating feeling that things could be different, or at least that they could still fail — a feeling never so deep when faced with the final product, no matter how beautiful or impressive it may be.

Latour, Reassembling the Social [p88-89]

Also, consider failure and its opportunities. Cf. Nicolas Nova on failures. Failures are situations that reflect on the assembly of things — err – their disassembly or their accidental destruction in a perhaps inglorious fashion.

But still — why do we want to see the made-ness of things this way? Is there more to be seen below the surface that reveals..what? The possibility of reconnecting things in other ways? That reveals the contingency of the construction — who was involved? What they did? Where the principles and sensibilities and politics of the thing are? Why was this fastener chosen over another possible one? To make it more secure and stable? Or to make the BOM cheaper and more likely to fly apart when dropped? Can you point to a part and say something about the principles of the design?

One insight from Latour that reflects on the importance of revealing the in-progress, in-construction aspect of things — things disassembled, or in exploded-view. These sorts of indicators of construction, constitution, assembly suggest a made-thing — which we always know if pressed that everything must be. Showing the components in-assembly or in-explosion suggests to us that this could have been done differently.

Why is this important?

Momentary Visibility Ways of bringing the associations amongst things into view. “Social” is a fluid visible only when new associations are being made..a brief flash which may occur everywhere like a sudden change of phase.

Why make the social visible?

Develop and execute — is this the preferred pattern of constructing things? No? Rather, might a more considered approach that learns lessons all the way down be design as perpetual iteration?

A list of situations where an object’s activity is made easily visible

Fortunately, it is possible to multiply the occasions where this momentary visibility is enhanced enough to generate good accounts. Much of ANT scholars’ fieldwork has been devoted to trigger these occasions..

1. Study innovations in the artisan’s workshop, the engineer’s design department, the scientist’s laboratory, the marketer’s trial panels, the user’s home, and the many socio-technical controversies.

2. Second, even the most routine, traditional, and silent implements stop being taken for granted when they are approached by users rendered ignorant and clumsy by distance — distance in time as in archaeology, distance in space as in ethnology, distance in skills as in learning.

3. The third type of occasion is that offered by accidents, breakdowns, and strikes: all of a sudden, completely silent intermediaries become full-blown mediators, even objects, which a minute before appeared fully automatic, autonomous, and devoid of human agents, are now made of crowds of frantically moving humans with heavy equipment.

4. Fourth, when objects have receded into the background for good, it is always possible — but more difficult — to bring them back to light by using archives, documents, memoirs, museum collections, etc., to artificially produce, through historians’ accounts, *the state of crisis in which machines, devices, and implements were born.*

5. Finally, when everything else has failed, the resource of fiction can bring — the the use of counterfactual history, thought experiments, and ‘scientification’ — the solid objects of today into the fluid states were their connections with humans may make sense. Here again, sociologists have a lot to learn from artists.

Latour, Reassembling the Social [p.80-82]

What is relevant here – possible tactics for design, assuming something has been made, without making it, and back-tracing the ‘controversies’ of its assembly. Assume you have only fragments of ‘what the thing was’ or ‘what the thing will have been’ and unpack it as an investigator/sociologist-of-associations/anthropologist/archeologist-of-associations; track back through the associations and construct what it might have been.

However, we worry that by sticking to descriptions there may be something missing, since we have not ‘added to it’ something else that is often called an ‘explanation’. And yet the opposition between description and explanation is another of these false dichotomies that should be put to rest — especially when it is ‘social explanations’ that are to be wheeled out of their retirement home. Either the networks that make possible a state of affairs are fully deployed — and then adding an explanation will be superfluous — or we ‘add an explanation’ stating that some other actor or factor should be taken into account, so that it is the description that should be extended one step further. *If a description remains in need of an explanation, it means that it is a bad description.*…As soon as a site is placed ‘into a framework’, everything becomes rational much too fast and explanations beging to flow much too freely. The danger is all the greater because this is the moment most often chosen by critical sociology, always lurking in the background, to take over social explanations and replace the objects to be accounted for with irrelevant, all-purpose ‘social forces’ actors that are too dumb to see or can’t stand to be revealed. Much like ‘safe sex’, sticking to descriptions protects against the transmission of explanations.

Latour, Reassembling the Social [p. 137]

So..what? Why do I blog this?

Is there anything about the sociology-of-associations and Actor-Network Theory that can become a part of a design practice that does more than incremental innovation? Or, what does the sociology-of-associations and ANT have to say about design practice? Why might it? Because ANT concerns itself with the making of things — or, also, the un-making to implicate practice in the creation of stabilized systems. Here, at the Laboratory, we are makers of systems that stabilize and cannot see how it would not be beneficial to understand how these systems stabilize — or at least to have an articulate point of view on how an idea hatched in California plops off the end of an assembly line 15 times a minute, 11 months later, and then get buried in the ground 24 months after that. And, if you understand — or have one or two of many possible articulate points-of-view on this — you have a better grasp on how to do this better, or perhaps how to decide in particular situations how not to do this, or how to design differently so that we don’t drown in things coming off of assembly lines 15 times a minute..only to end up filling land 24 months after that.

Institute for Conceptual Technology — for real.