Back for a bit to the world of prototyping peculiar Near Future kinds of things. I’m still working through this anti-game controller, game controller to do some experiments in alternative sorts of mobile interfaces for traditional game devices.

First, there are two other posts on the Logicport and related stuff, and I’ll just flag them here:

Logicport and I2C

Logicport Overview

I did some quick experiments with the Logicport to get my head around its operating features. (My previous brief analysis is here.) I was mostly motivated to work with a logic analyzer because many of the prototyping sketches I do require some sort of communication between devices using protocols like I2C/TWI, SPI or standard serial communication. If you can get these protocols to work right the first time, then you’re golden. Sometimes though, something goes wrong and debugging can be a pain. I’m the kind of guy who likes to see what’s going on rather than guess, and tools like a digital scope and logic analyzer are indispensable for me. It’s just a preference I have to invest in some pro gear, within a reasonable budget. Seeing as I was trying to get this PSX project done and had trouble debugging it, I figured this was as good a reason as any to go ahead and get it and figure out how to use it.

The Logicport is pretty reasonable for a 34 channel (plus 2 dedicated clock channels) logic analyzer because it offloads a lot of the heavy lifting to your PC — $389 with everything you need except the computer. I told myself I’d get one when I had some trouble debugging what should’ve been a fairly straightforward interface — hooking up a microcontroller to a Playstation 2 to make the PS2 think the microcontroller was the normal Playstation controller. This got a bit tricky to debug with just a digital scope that had only two channels with which to analyze essentially a protocol that was using five channels.

[ad#ad-4]

The Playstation 2 interfaces to its controllers using a protocol that is basically SPI (Serial Peripheral Interface). The protocol for SPI is fairly straightforward. There’s a clock (SCK) to synchronize bits of data across two channels: Master Out, Slave In (MOSI); Master In, Slave Out (MISO). MOSI bits are data moving from the master device to a slave device. MISO bits are data moving from the slave out to the master. It’s like a two lane highway of data, with each data bit synchronized by the clock. Additionally, there’s a “slave select” (SS) channel — one per slave device — that tells the slave whether or not it is “active” and should listen to data bits coming across the MOSI channel, or send data bits across the MISO channel. (Reasonably, only one slave device should be active at a time.)

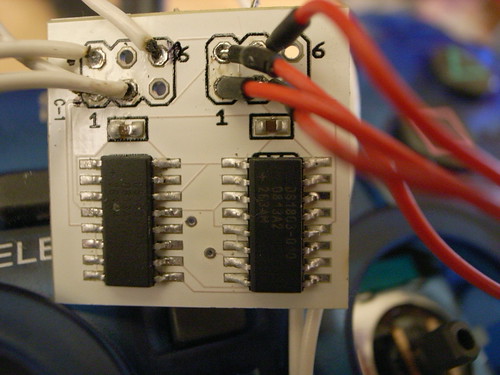

So, that’s four channels. The Playstation 2 actually uses this plus an additional line that is not specifically part of the SPI protocol — an “Acknowledge” (ACK) line. This is used to “acknowledge” to the Playstation 2 console each “frame” of data. That’s just the way it works, and the one feature that is a bit outside of the SPI protocol. (I fabbed-up a simple splice along the Playstation 2 controller cable to watch the protocol and try and figure it out. The splice has a simple IDC-style connector that I can use to plug into to either read the channels or, eventually, connect to a microcontroller.)

There are a few pages online describing the specifics of how a Playstation 2 controller works, including ways to interface the controller itself (the joystick) to microcontrollers.

What I’m trying to do is that, but a bit more, which is to interface a microcontroller that behaves like a Playstation 2 controller to the Playstation 2 console. To do this, the microcontroller needs to respond as a (kinda) SPI slave device, just as the Playstation 2 controller does.

To start this whole business, I tried first writing code “blind” — just looking at descriptions people had put up of how they did this, especially Marcus Post’s work, which has some PIC code to look through. I ported this as best as I could to the Atmel platform (running on a 16MHz Atmega168 on an Arduino), but was having some “hiccups” where quite often the Atmega168 seemed to loosethe protocol. Why? It was hard for me to figure out.

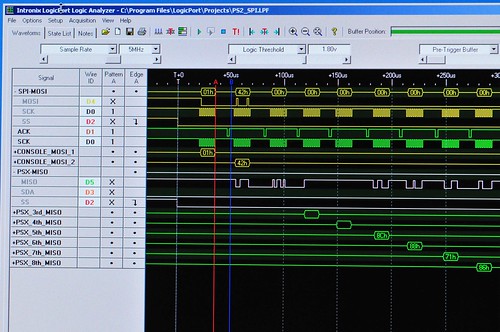

So, two things going on here. One — verify the console-to-controller protocol that the Playstation 2 uses. Two — figure out how to use the Logicport. I’m going to leave two for later, and first show the analyzer crunching on the PS2 console-to-controller communication.

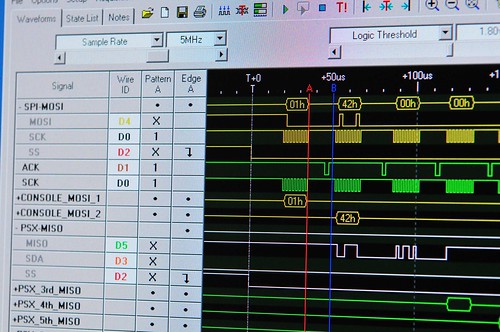

Okay, first thing I did was connect up six of the Logicport’s 34 channels as if we’re analyzing a SPI protocol which, basically, we’re doing. We need MOSI, MISO, SCK (clock), SS (slave select), plus the ACK channel. We also need a ground line to have a common electrical reference. These signals are analogous to the one’s the PS2 uses, only with somewhat different names — they are CMD (MOSI), DATA (MISO), CLOCK (SCK), ATT (SS) and ACK in PS2 speak.

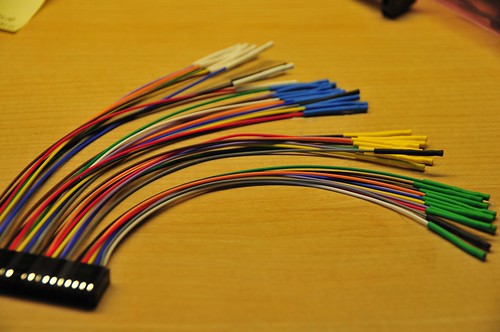

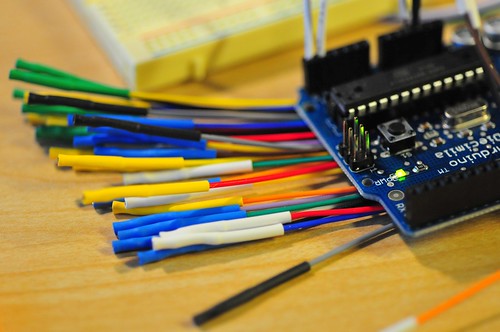

The Logicport breaks up its 34 channels into 4 groups of 9 channels (that’s 36, but two of them are dedicated clock channels), with each group color coded by a bit of heat shrink tubing on the end of a colored wire. This makes it easy to figure out which channel is being represented in the software display. (Here’s a plug module that pops into the Logicport. These are convenient cause you can have one semi-permanently connected to individual projects so you’re not always re-wiring. Just save the Logicport file for each project with the same channels and pop the plug module into the main Logicport box.)

So, I just took the “white” group and connected the MOSI, MISO, SCK, SS and ACK channels from the Playstation 2 “splice” cable. I used yellow for MOSI/CMD, black for SCK/CLOCK, red for SS/ATT, brown for ACK, and green for MISO/DATA. With these signals connected from my “splice” cable to the Logicport, I should be able to start seeing the acquisition. (I’ll go over setting up Triggers and Interpreters in a later post. For now, let’s just see what a little fussing gets us.)

The Playstation 2 protocol is pretty straightforward. It starts out with the console activating the SS/slave-select line (channel D2, red/white) to indicate to the controller to start paying attention. SS is active low, so the channel drops from high to low to indicate “pay attention now.” Following this is a 0x01h byte of data along MOSI/CMD — channel D4, yellow/white. You can also see how the Interpreter can represent the data across a specific channel by aggregating bits and turning them into something useful, like a hex number. (You can also fold up these groups of channels if you don’t want to stare at individual bits.)

So, this is the basic preamble for communicating between the console and the controller. After the 0x01 the console sends the command 0x42, which basically means — send all your data. Simultaneously, the controller sends back a specific ID to indicate which type of controller it is. In this case, the controller ID is 0x79. Following this the controller sends a 0x5A to sort of say — data is coming.

The data that follows is basically the state of all the controller’s buttons and the analog controls’ positioning. For this controller, there are six subsequent bytes of data. For this particular controller, they’re like this (Here’s a more complete table for other kinds of controllers.):

Analogue Controller in Red Mode BYTE CMND DATA 01 0x01 idle 02 0x42 0x79 03 idle 0x5A Bit0 Bit1 Bit2 Bit3 Bit4 Bit5 Bit6 Bit7 04 idle data SLCT JOYR JOYL STRT UP RGHT DOWN LEFT 05 idle data L2 R2 L1 R1 / O X |_| 06 idle data Right Joy 0x00 = Left 0xFF = Right 07 idle data Right Joy 0x00 = Up 0xFF = Down 08 idle data Left Joy 0x00 = Left 0xFF = Right 09 idle data Left Joy 0x00 = Up 0xFF = Down All Buttons active low.

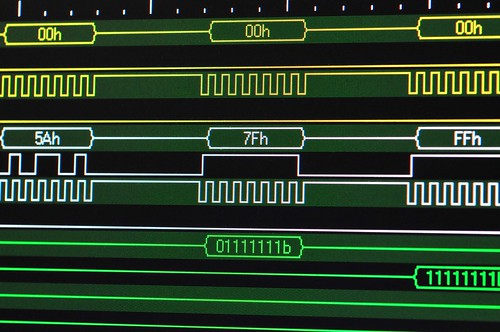

For example, the acquisition image at top shows the “LEFT” arrow button being pushed down on the controller. Huh? Yeah, see — the right most bit in the white trace? It’s actually low — a little hard to tell cause of the angle, but it is. The PS2 spits out data least significant bit first, which means that bit 0 comes before (in time) bit 7, so the 0 at the end is bit 7, and bit 7 in byte 4 indicates whether the LEFT arrow is pressed, and everything is active low here, so a 0 means — pressed. (As I understand it the SPI protocol normally is the other way around, but luckily with the Logicport you can specific the bit ordering.)

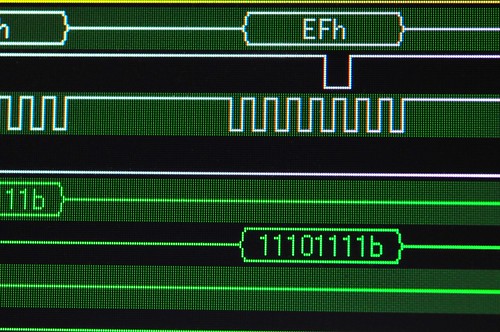

Byte 5 is for the other buttons. This image shows bit 4 activated (low) indicating that the triangle button has been pressed. The bytes that follow are the the joysticks to indicate their positioning along their two (left/right, up/down) axes, running between 0x00 and 0xFF, with their “nominal” (centered) value being about 0x8C-ish, depending on how sticky they are and other things — they’re analog potentiometers which have a little bit of tolerance for variation for mechanical reasons and such.

Here’s an overall view of the entire transaction — the three bytes of preamble, followed by six bytes of controller state data starting around the 100uS. (Those bytes are near the bottom, staggered, in green. Next time I’ll explain how I set that view up.)

(Note that the acquisition shows that the console actually holds the SS/ATT signal for the equivalent of another six bytes of data. I’m not 100% sure why, but perhaps there could be additional data bytes for this sort of controller that I’m not getting. In any case, both the console and the controller send nothing back and forth. It’s just clocked nulls for another six bytes. So, off to the right of this image is lots of clock signals, and ACKS, but no meaningful data, until the SS pulls back high. Also notice the ACKS in the fifth channel (green) — these are acknowledge signals sent from the controller back to the console to verify that it’s alive and so forth. Evidently, these are necessary for the communication to work, but not strictly part of the SPI protocol. (Also, I am calling this SPI because it’s close enough, and provides a bit of a context for describing the communication and taking advantage of the Logicport’s SPI Interpreter. Technically I suppose it isn’t SPI.)

What’s next? Well, a brief overview of how I configured the Logicport to acquire the protocol data. And, now that I can actually see what’s happening and have a better understanding of the SPI-like console-to-controller communication, I should be all set to make a microcontroller behave like a Playstation 2 controller so I can spoof the PS2 and control it from other kinds of things.

[ad#ad-1]