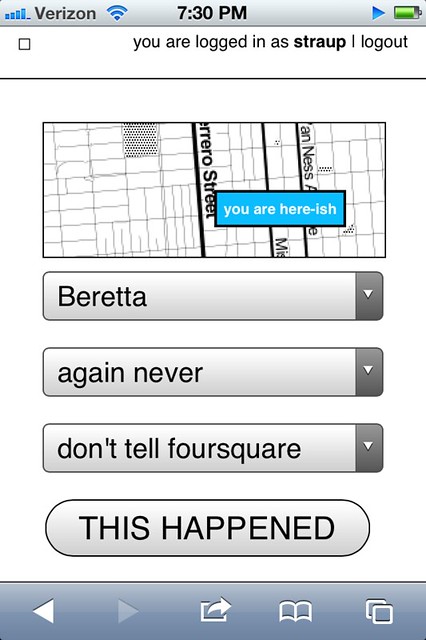

I’ve been working on, and testing out, a new thing for the last couple of weeks. It is called privatesquare. It is a pretty simple web application that manages a private database of foursquare check-ins. It uses foursquare itself as a login service and also queries foursquare for nearby locations. The application uses the built-in geolocation hooks in the web browser to figure out what “nearby” means (which sometimes brings the weird but we’ll get to that later). On some levels it’s nothing more than a glorified check-in application. Except for two things:

First, when you do check in the data is stored in a local database you control. Check-ins can be sent on to foursquare (and again re-broadcast to Twitter, etc. or to your followers or just “off the grid”) but the important part is: They don’t have to be. As much as this screenshot of my activity on foursquare cracks me up it’s not actually representative of my life and suggests a particular kind of self-censorship. I don’t tell foursquare about a lot of stuff simply because I’m not comfortable putting that data in to their sandbox. So as much as anything privatesquare is about making a place to file those things away safely for future consideration. A kind of personal zone of safekeeping.

Second, privatesquare has its own internal taxonomy of event-iness. It is:

- I am here

- I was there

- I want to go there

- again

- again again

- again maybe

- again never

The first item maps the easiest to foursquare’s model of “checking in”. It is what it says on the tin. The second is the thing that you can’t do on foursquare but everyone does anyway: Checking in after the fact if only to have a personal record of things you’ve done. This just makes the act explicit. The third is not unlike the “lists” feature that was introduced on foursquare, last year. It is also the one flavour of check-in that is not forwarded on foursquare. I suppose I could figure out how to add things to a list, but I haven’t yet.

The last four are a long overdue love song to Chris Heathcote and a plaintive desire for something like the Dopplr Social Atlas (not to mention Dopplr itself) but one that isn’t held hostage to the seeming neglect of its parent company, Nokia. Once upon a time, I went to Helsinki for Important Business Meetings ™ involving Flickr and Nokia while Chris still lived and worked in Finland. I asked him where I should eat during my stay and he sent back a long list of restaurants (all lunch places, I think) each flagged as “again”, “againagain” and so on.

The Social Atlas was a feature added somewhere around year two at Dopplr and is a list of places to eat at, stay in or explore. Places are added by the users and organized by city. It remains a lovely example of how to do this sort of thing though there’s not much going on there these days. You can flag as place as somewhere you’ve been, somewhere you like but not someplace you dislike. Which always seemed like a shame because I would find it helpful to know that someone I know and trust dislikes a restaurant in London as much as I despise Herbivore, in San Francisco.

Chris’ is a genius classification system. It does not get lost in the weeds of weird similes and absurd metaphors (wine tasting, anyone?) and by and large captures the experience of asking someone where you should go to eat in a place you’re not all that familiar with. It is also entirely bound to the relationship of the person telling and the person asking. It is not a recommendation engine.

It assumes that although two people would both do something again, or do it enthusiastically (“againagain”), they are just as likely not to do the same thing. Those details are left out of the equation (read: the computer) because it will never be able to account for the subtlety and history of experience between two people.

The “again” ratings (markings, like on a tree?) are an odd lot in that they don’t go out of there way to distinguish themselves in time. Is it just an indication that you went there some time in the past and want some record of the event? Or does it mean that you wait to check-in until you’ve decided how you feel about it? Or do you check-in and then say whether it was good or not?

I am very consciously punting on these questions for the time being in order to see how the thing actually gets used and what I find myself wishing it did. I suspect that most of the confusion that may be generated by these kinds of blurry and overlapping assignments can be overcome by displaying dates and times clearly.

It is worth nothing that privatesquare does almost nothing that foursquare doesn’t already do, and better. privatesquare is not meant to replace foursquare but is part of an on-going exploration of the hows and whens and whys of backing up centralized services with bespoke shadow, or parallel, implementations of the service itself. It is designed to be built and run by individuals or as a managed service for small groups of people who know and trust one another.

privatesquare remains a work in progress and I am not planning to run it as a public service any time soon but it is available as an open-source project, on Github, that you can run yourself:

http://straup.github.com/privatesquare/

The documentation and installation process still remains out of bounds for most people who don’t self-identify with the nerd squad but that will sort itself out over time. For what it’s worth my copy is running on insert a vanilla shared web-hosting provider that can run WordPress here so that’s a promising start, I think.

The site is built on top of Flamework, which is a whiteroom re-implimentation of the core libraries and tools that a bunch of ex-Flickr engineers used to build Flickr, the same way that parallel-flickr is. Meaning that some part of all these projects is just putting Flamework through its paces to find the stress points and to better understand the hows and whats of the process (installation, documentation, gotchas and so on) should be. And like parallel-flickr “it ain’t pretty or classy (yet) but it does work.”

Here’s an unordered list of the things privatesquare still doesn’t do:

-

Sync with the foursquare API. For a whole bunch of reasons you might find yourself checking in to foursquare using another client application. privatesquare should be able to fetch and merge all those check-ins that it didn’t handle first.

-

The “nearest linear” cell-tower problem. This is one of those problems that gives credence to all the hyperbolic hand-waving done by companies driving around mapping latitude and longitude coordinates for wifi networks. Without this data determining geographic location for a web application running on a phone is often handled by assuming that whatever cell tower your phone is connected to is “good enough”. Sometimes it is but just as often it’s not. You have a line-of-sight, a signal, back to a cell tower that exceeds the maximum radius in which to query for venues. Because your phone thinks you are somewhere else you always end up falling outside the hula-hoop of places that are actually near you.

The map that’s displayed with venue listings (there’s a screenshot at the bottom of this post) is one possible alternative. As I write this the map isn’t responsive. It’s just there to try and help you understand why a particular list of places was chosen. Eventually you should be able to re-center the map to a given location and use that when looking up nearby venues, for those times when your web browser can’t figure out who is on first by itself.

-

There is no ability to delete (or undo) check-ins.

-

There is no ability to add new venues. Nor is there any way to record events offline or when you don’t have a network connection. I’m not sure whether either of these will ever happen. At the moment there are just too many other things going on. Beyond that I sort of like the fact that privatesquare doesn’t try to do everything.

-

There is no way to distinguish duplicate venues (same name, different ID).

-

Export, which is probably the single most important thing to add in the short-term. This includes a plain old web view of past check-ins.

-

Pages for venues, though I’m really sure what I was thinking when I was blocking out this blog post and wrote that. It’s probably related to what I wrote about cities (below) and the idea that the really interesting aspect of a venue page is seeing a user’s arc of again-iness for that spot over time.

-

Pages for cities. The other nice thing that privatesquare does when you check-in is “reverse geocode” the location of the venue and store the Where On Earth (WOE) ID of the city the venue is in. Which will make it possible to build something that looks like the Social Atlas. For example, if you were going to Montréal I might send you a link to all my check-ins in that city (WOE ID 3534) tagged “again”, “againagain” and “I want to go there”.

In a way privatesquare is just the foursquare version of parallel-flickr: a tool to backup your check-ins, albeit pre-emptively. Which is sort of an interesting idea all on its own. The differences between the two applications are that parallel-flickr doesn’t let you upload photos (yet) and privatesquare doesn’t really provide any mechanism for sharing your check-ins with a restricted set of users. Currently, it’s all or nothing (read: “nothing” because the code forces you to be logged in before you can see anything).

I am also thinking about forking; piggybacking; hijacking (piggyjacking?) some or all of the work that Stamen has done with the Dotspotting project. For two reasons: First they are both built on Flamework so it ought to be possible to make them hold hands without too much fuss. Second, there’s a nice un-intended feature in the way the code for browser things and the code for database things handle the data that people upload to the site: HTML tables.

In theory (and I haven’t tested this out yet) anything that can generate an HTML table, with the relevant semantic attributes, and send it to the browser along with the relevant JavaScript code will be able to take advantage of all the lovely display and interaction work that Sean Connelley and Shawn Allen did for Dotspotting. Just like that!

The reason this all works is that when we started writing Dotspotting it was during a time when Flamework was still pretty green and lacking any code for doing API delegation or authentication. Rather than trying to shave that particular yak we simply opted to use the HTML sent to the browser and jQuery as a kind of internal good-enough-for-now API.

Once it’s sorted for privatesquare it should be easy enough to swap out the table parsing code with proper API calls, now that Flamework has its own API delegation code, and then it could be dropped in to parallel-flickr as an alternative view of your geotagged photos.

It’s all still magic-pony talk and none of it addresses mobile (tiny) web browsers or anything but a pretty conventional linear paginated view of the data (no clustering or other fancy stuff) but, still: This pleases me.

In the short-term I’m going to continue to focus primarily on the data input side of things trying to make it as easy and fast as possible to record the data along with the simplest of CSV or GeoJSON exports, so that you could at least look at your data in tools like Dotspotting or Show Me the GeoJSON respectively.

And if I can get that part squared then it also might be possible to re-use some of the same work to make things like Airport Timer easier since the two projects are each a kind of side-car to the other, when you stop and think about it.