The work in mapping the connection between physical geography and virtual representations of that geography is a component of the work I have done that is relevant to the question as to what the basis of my tenure case is. In retrospect, I realize that I picked up the story in the middle, and that there is a preceding “chapter” to my intellectual work since my work as a graduate student. I would like to recast this personal narrative with a brief supplement that explains the continuity of my work since graduate school.

The vector of the scholarly and art-technology work I have done investigates ways to connect the physical world with the virtual world. The online virtual world brought about manifest changes for how we live within and socialize as human beings. It is my speculation that a “connected world†in which the virtual and the physical are linked, not only amongst human beings, but also network connected non-sentient “things†— will be the next evolution in the new networked age.

As explained in my Personal Statement, many of those “connecting things†projects took the form of creating linkages between the physical world as represented as geography, and the virtual world as in visualizations and representations of that geography. This was some early projects in exploring digital cartography, the most literal kind of link between the virtual and the physical. There was work, though, that preceded these projects that I feel is significant and crucial to a more complete description of my scholarly trajectory.

There are three “chapters” to my research work, and each has consumed between 3-5 years. Virtual reality was the main character in the first chapter, and was the focus of my master’s of engineering studies and my doctoral dissertation. Mobile devices was the focus of the second chapter and consisted of a series of art-technology commissions that lasted 4 years during the completion of my doctoral dissertation and into the first year of teaching at USC. The third chapter, which I began at the early part of my second year at USC, is focused on how electronic games that link physical world data sensing with virtual world games can address two real-world challenges — the state of the environment and adolescent physical fitness.

The first “chapter” of this research trajectory began with my master’s studies on virtual reality and the cultural and technological ways that virtual reality set itself off as distinct from physical reality. For my master’s research, I studied computer-human interaction and learned how the human body can become an interface — a connecting bridge — between the virtual and the physical. My chief interest was to study how virtual reality could possibly lead to richer, more evocative, more natural connections between our physical bodies and virtual bodies as a form of human-computer interface. This was the core of my studies as a master’s student and a doctoral student — studying virtual world to physical world connections — the human-computer interface. One chapter of my dissertation became well-regarded as one of the earliest analyses of video games, in this case SimCity, a game that links representations of physical worlds (cities) to virtual worlds (the computer simulation.) In the work that lead to this chapter — a series of studies of people playing this game — I began to recognize that the computer-human connection can be understood both at the physical level as well as the cognitively level. This realization would become a valuable consideration in the “third chapter” as I work to find ways to create connections between physical and virtual worlds that persuade people to modify their habits and behaviors.

The second chapter is about digitally connected mobile devices as connectors between things happening “on the ground” in physical environments beyond the heads-down computer desktop experience, and the virtual representation of those activities online, on the Internet. In this chapter, I created mobile devices and device-based experiences that allows users to create and share their own personal maps of the world around them. This work presaged the popularity of online, user-created maps of popular or significant locales before the introduction of the popular commercial online mapping services.

The third chapter, just now beginning, is focused on linking the virtual and the physical, where the specific parameter of the physical world is represented by two different things, for two separate but related projects: physical fitness and the physical environment. I will explain each briefly in turn. (As this work is in progress, a complete description and summary results are premature. One project is sufficiently advanced at this stage that it is being submitted for consideration at user-interface design professional society conferences.)

The first project in this third chapter is body-based fitness activities. The second project in this chapter is sensor-based readings of the “micro-local” state of the environment.

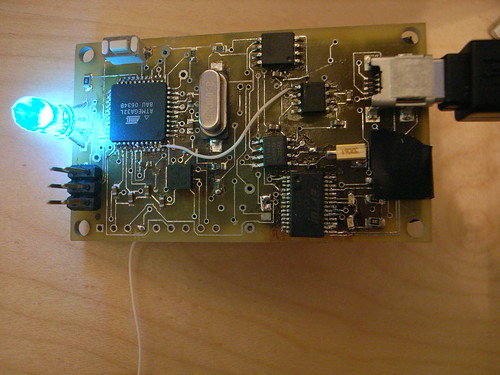

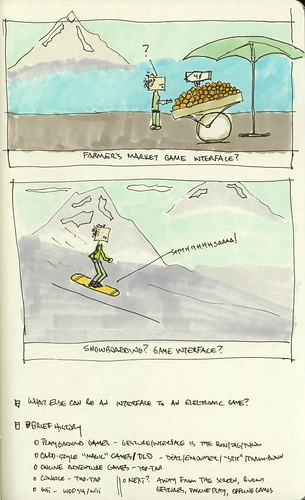

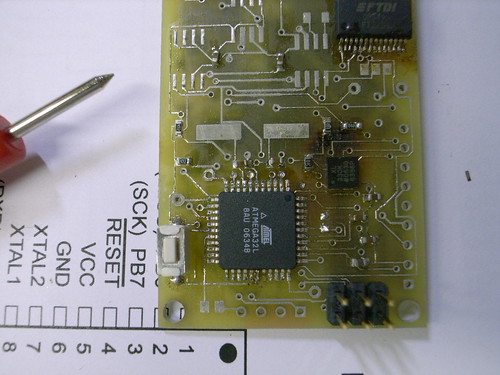

For the first project, my course of research, which is approximately 30% complete, is to create small evocative games that connect physical fitness — real-world physical activities such as might be compelling for young adults, for example, skateboarding, basketball, snowboarding, walking — with online digital games. I am constructing a “theory object” that creates a bridge between physical activity and virtual activity. This particular “theory object” is an inexpensive device that can record arbitrary physical activity, and do so in a way that addresses many of the important characteristics of a successful physical fitness regimen. The objective is to allow physical play to also appear as compelling as virtual play. The project is meant to evoke in the user the sense that their physical play will also contribute to virtual play. By connecting physical activity with virtual activity I am hoping that the propensity many youth have for online experiences will encourage them to invest their time with a mix of physical and virtual gaming.

The second project for this chapter is to create a series of games about the environment by connecting physical world sensing of the “micro-local” environment to a virtual world representation of the sensor data. I am designing and constructing a hand-held, portable device capable of sensing environmental pollutants that will produce data that can feed into a small game. The objective is to evoke concern for the environment and turn attention more directly toward environmental issues.

With both of these “third chapter” projects, my hope and expectation is that USC’s preeminence as a center for research and development of electronic, online games will further buoy the significance and importance of this third chapter of research. This kind of virtual/physical hybrid electronic game is a conceptually rich area of research and is just at its early stages. A search of the canonical idiom for this new arena — “exergaming” — on the ACM digital library yields four citations, three of which are informal interviews with leaders in the field of human-computer interfaces. Only one citation makes an extended study of pedometers as a way of encouraging physical fitness, and the paper itself yields no remarks on the construction of more complete game scenarios. In other words, the ground is fertile for defining the terms and debate of this area of gaming that connects the virtual and the physical, an area of research practice that I have called “offline gaming.”

Results and Publication

The first chapter as described above yielded a long (100+) page essay that became my master’s thesis and further investigation and study of that first chapter yielded my doctoral dissertation, completed in 2004. One chapter from the dissertation was published as a journal article, and reprinted in a book on the popular computer game SimCity. The third and current chapter serves as material for a book project with the working title “Connecting Things”, about how connections between the virtual world and the physical world can mitigate the deleterious effects of relying too much on one rather than finding a careful, connected balance between the two. The underlying theme of this book has been presented and refined in a series of invited public and conference lectures as well as small research workshops I have facilitated over the last two years. (I have included slides from several of these presentations, as well as reports and essays on the book’s main theme in the dossier.)

The book will consists of scholarly theoretical essays, research results, and designed devices of my own making (what I refer to as “theory objects” and others refer to as evocative knowledge objects) constructed as open-designs (open-source/open-hardware/open-process) so as to help explain the book’s thesis through their actions.

More Detail of My “Connecting Things†Research Vector

From VR to Mobile Devices to Connecting Sensor Things That Link the Physical to the Virtual

1. “Chapter One†— “Virtual World” as in Virtual Reality

My master’s thesis, completed in 1993, investigated how the physical and virtual became conceptually distinct. I looked closely at popular news media, science-fiction and film to understand how “virtual reality” was represented and how its representation changed what people understood to be the possibility of unique connections between the physical world and the virtual world. This was a watershed moment in the study of human-computer interfaces, and helped pave the way for expanding the study of connections between humans and machines.

For my doctoral studies and my dissertation, completed in 2004, I performed a close study of the technology behind virtual reality and computer simulations.

I did this so I could understand how technology can shape the way we think about and understand the world. My goal was to learn how to do such a scholarly analysis — and do it convincingly — so as to learn how I might myself create technology devices and objects that evoke within the mind of the technology’s user that the physical world matters.

As I completed my dissertation I had embarked on a series of “art-technology” theory objects. These were technology objects commissioned as artistic projects that continued my theme of finding ways to connect the physical world with the virtual world, and do so as to deepen a sense of commitment to the physical world. These projects were driven by a deep personal sense of anxiety regarding the state of the physical world’s ecology. My concern was driven by the enormous attention that “virtual worlds” were receiving as the Internet continued to grow in importance. I felt an obligation to research ways to make the Internet more “physical” or to make it more directly associated with activities and places in the normal, geographic world.

2. “Chapter Two†— Virtual Worlds in Mobile Devices

The PDPal series of projects were a collaborative effort to turn to mobile devices that were connected to the Internet. The reasoning behind choosing the PDA (personal digital assistant) was that they were a digital device associated with digital networking, only they were chiefly designed for use while one was engaged in a physical world activity — walking or at least away from the canonical digital device, the desktop personal computer. These projects force the user to consider their surroundings by asking them to record the activities going on around them. By looking up and engaging the physical world, the user’s appreciation and attention to the physical world increases. This application runs counter to many of the early PDA softwares, which were simply smaller versions of the same desktop applications one was used to, with no evocative link to the physical world. To actually create the connection between physical and virtual, PDPal had an online community where people could upload their recordings to be shared in a PDPal virtual world.

Two art-technology projects (theory objects) I developed on my own used the developing technology known as WiFi, used for wireless digital networking. I chose to use WiFi because it was most often associated with mobile computing, hence offered a new (at the time) style of networked computing that is happening in the physical world — at a cafe, in a park, airport, etc.

My research agenda was to find ways in which WiFi could create connections between the physical world and the virtual world of the Internet. WiFi was suitable because it is safe to assume that one is going to be “closer” to and more attentive to activities going on in public, physical places.

I created two devices to allow me to learn about how WiFi in quotidian physical places could allow a user to simultaneously be online in the virtual world of the Internet, while still attentive to their physical world surroundings. WiFi.Bedouin was an apparatus that created a fully mobile wireless access point that could be carried in a backpack. It was one of the first instances of making WiFi mobile. The second device called WiFi.ArtCache, performed a similar function, but provided a unique networked service by reversing the notion that digital media is infinitely reproducible. All of the digital resources on the device — files, media, etc. — were limited in quantity and were unique in the sense that one had to be physically within range in order to download the media. Thus I was able to study the affects of an enforced scarcity of digital media and begin to question how scarcity of resources in virtual worlds can teach us about scarcity of real-world resources. (This project won the “People’s Choice Award” in 2006 at the International Society of Electronic Arts Biennial Festival and Symposium.)

The capstone to my work in connecting the physical and the virtual was a project I conducted during my first summer as a professor at USC. In collaboration with Peter Brinson, another faculty member, I created a project called “Vis-a-Vis†(Face-to-Face) that was a kind of digital binocular. The device was a viewing portal into which one looked at a scene rendered as a video game world. The scene was fairly conventional, except that it was rendered on a small, flat-screen, portable Tablet-PC. One held the Tablet-PC in front of oneself, as if reading a newspaper, and as one pivoted the screen to the left or right or tilted it up and down, the point of view seen through the screen trained appropriately, as if the Vis-a-Vis device were a magic portal into the game world.

This project was an early attempt at extending the connection between the virtual and the physical to a very direct, physical movement interface. This project lead directly to project designs and experiments in connecting physical movement to virtual worlds activities, such as effects in electronic games.

3. “Chapter Three†— Virtual Worlds as in Connected Devices

(Preliminary work, in-progress.)

The projects I am working on presently are very much in-progress. They are experiments in connections between virtual and physical worlds that operate “asynchronously.†This means that the data gathered in the physical world is not immediately sent to the virtual world. The purpose of this particular design strategy is to explore the possibility that some connections between the virtual and physical need not be “always on.†The notion that the world will be blanketed by continuous network coverage is, I believe, a conceit born out of the hubris of engineers and network service providers. With every possibility, there are very many alternative possibilities. In this case, I would like to explore how connections can be partial and “seamful.â€

For this stage of my current research, I am designing devices and software for a series of electronic games specifically designed for non-gamers, such as myself. The first translates “ambient†physical activity into game play events. The second uses CO2 sensors to capture the level of pollution in the micro-local ecosystem, turning pollution levels sensed into a game about saving the world. The third is an extension of Eric Paulos’ and Liz Goodman’s Bluetooth sensing “Jabberwocky†project, turning the concept of urban “Familiar Strangers†hypothesized by Stanley Milgram into a game that forces the player to recognize the density of invisible connections between people in the world.

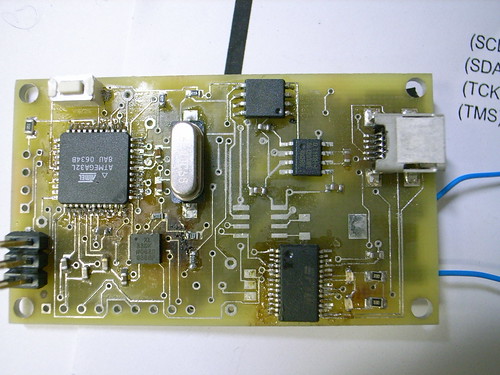

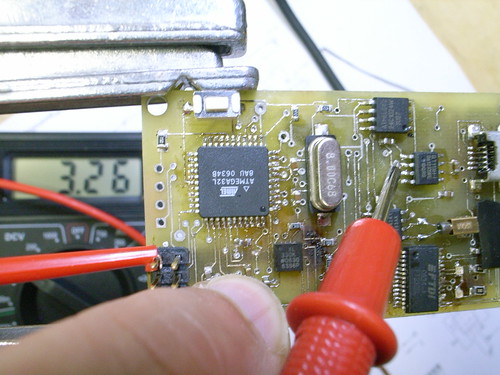

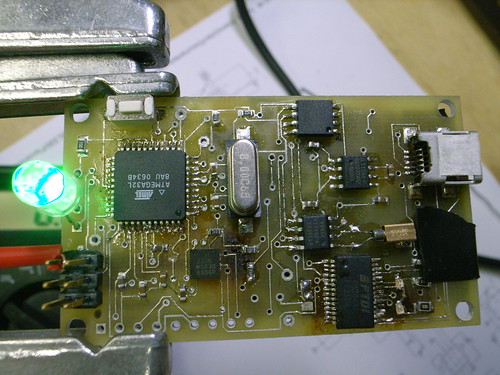

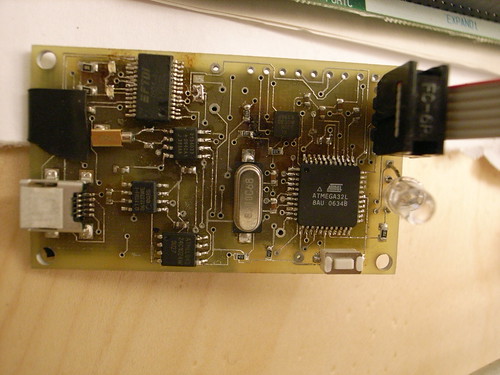

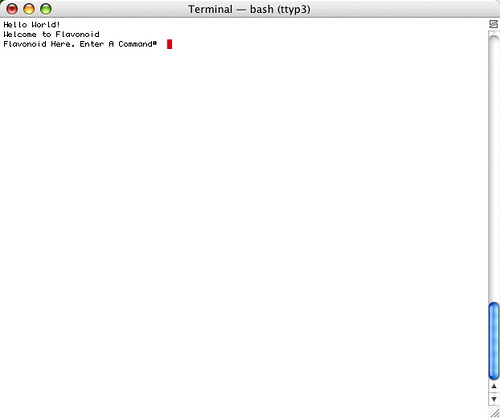

The first project uses a device I designed to record ambient physical activity by the device’s owner. This movement is richer and more subtle than that captured by a pedometer, as one of my design requirements was that it be able to capture nearly any kind of physical, body-based activity. This kinetic activity is translated to “energy†or “power-up†in an electronic game context, which is still to be determined. This project is the framework for what I imagine to be a style of gaming I’m calling “offline gaming†in which a player can play the game without having to be sitting in front of a screen or distract themselves from the immediate, physical world activities immediately in front of them.

The second project uses another device I am designing to capture the levels of CO2 in the immediate environment. These readings are accumulated and become “negative energy†in an electronic game. This negative energy will result in a decline of some sort in the game world, which can only be mitigated by the player engaging in some physical world activity that is generally perceived to be eco-friendly, such as riding their bike, recycling or driving an eco-friendly vehicle.

Both of these projects continuing my research in the area of connecting the physical and virtual, or “1st life†and “2nd life†with the purpose of encouraging behaviors that will hopefully lead to more habitable, life-affirming, sustainable, healthful worlds.