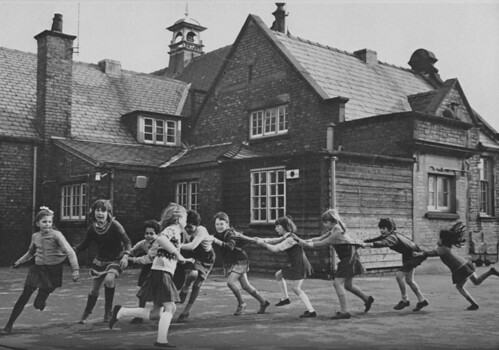

Aaron Meyers deployed this turn of phrase “human joystick” during his final presentation for the course I taught this semester — “Design and Technology for Mobile Experiences.” He’s been working hard mostly on his thesis project, Torrent Raiders, but for my class he worked on programming a J2ME version of the MobZombies game that’s been percolating around the Interactive Media Division since 2002.

I’ve been interested in expanding the kinds of interfaces we have to digital worlds, and doing so to explore what computing can mean, besides the kind of computing we assume computing means. My speculation is that, to a significant degree, the “point of entry” defines and shapes what we imagine computing is, and it will not become much more than what it is so long as our point-of-entry are a flat visual display, a small squares of plastic that we push about 2 millimeters, a ball of plastic we swish around a flat surface. It boggles me when I think that this basic setup has been around, little changed, for 15 years, and much longer if you factor the computer mouse out of the framework. Boggles me.

And it’s not for lack of effort. The Wii-style wand concept has been bandied about at any number of professional/academic research contexts. Ten years ago a music conductor’s baton was the concept behind a project that, initially, was designed to control electronic music using conducting gestures. The researcher, Teresa Marrin, became so enamored with the possibility of gesture as a computer-human interface that she saw it not only as a device that could be used as a “new instrument on which to perform computer music” but also as “a model for the design of new interfaces and digital objects.” The interesting thing is that it’s more than a 3D mouse in many regards — it’s usage context is explicit in the object. The hardware is remarkably prescient:

The sensors on the baton include an infrared LED for positional tracking, five piezo-resistive strips for finger and palm pressure, and three orthogonal accelerometers for beat-tracking. Both the infrared sensor and the baton send separate data streams (including values for absolute 2D position, 3-axis accelerometer, 3-axis orientation, and surface pressure) via cable to the tracking unit, which converts the signals to the computer.

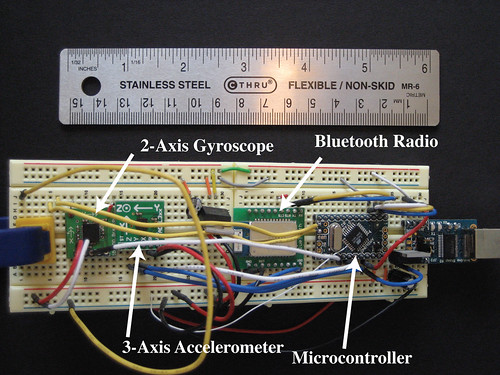

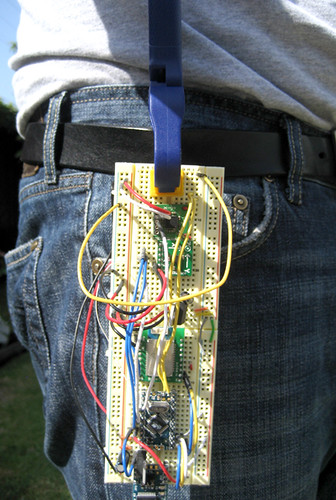

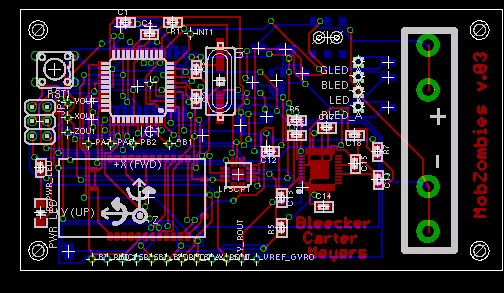

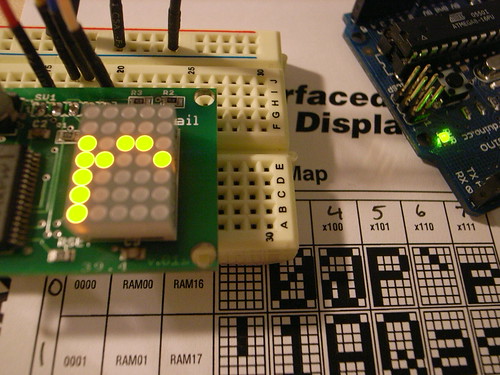

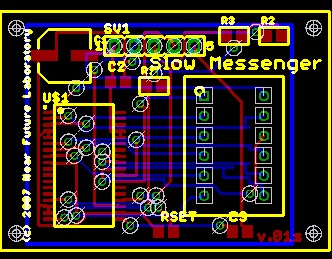

Over the last month or so, I’ve been constructing a sensor prototype that would turn the human into a human joystick for the MobZombies game. It combines a 2-axis gyroscope and 3-axis accelerometer, a microcontroller and a Bluetooth radio to transmit the data to the game display device, a mobile phone. The motivation here is two fold. First, investigate what a mobile game can be, that evokes both traditional playground style pre-digital action. Second, set up a baseline experiment for how computing can move away from the fixed office desk and make use of human body movement as an interface.

If you haven’t seen the “trailer” for MobZombies, I recommend checking it out.

(I’ve always wanted to make one of these specimen style graphics, with the ruler and callouts? You know?)

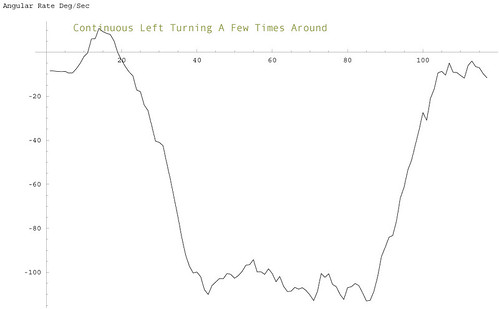

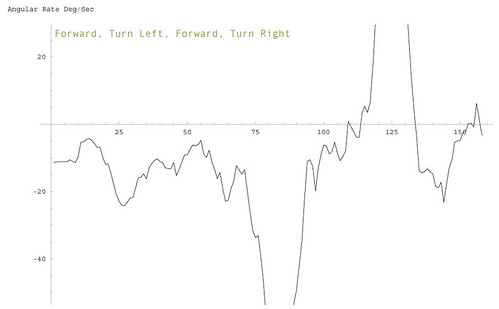

When I first cobbled the sensor together, I was hoping to use a magnetic compass like the previous version of the game controller used. It was a bit too sensitive to the RF energy created by the Bluetooth radio and I couldn’t easily find a way to separate the two without making a large design or diminishing the capabilities of one or the other. So, I turned to a MEMS gyroscope by InvenSense — the IDG300, which is a fast little gyro. I ran some quick tests which pretty much showed me that it was plenty fast. In fact, I could probably even go slower and maybe use a lower-end unit and save a few scheckles. I quickly cobbled together a bit of code bolted onto Aaron’s J2ME prototype. Turning motion is spot-on, which was a welcome surprise.

The MobZombies human joystick style interface is fun and suggestive more than it is a tectonic shift in how we interface with our devices. But, this style of interface is coming — it’s already here in some contexts. Nokia has introduced the 5500 Sports Phone with integral tri-axis accelerometer. I’ve heard tell of mobile phones that use the camera to detect and interpret motion by computing changes to the visual field. Etc.

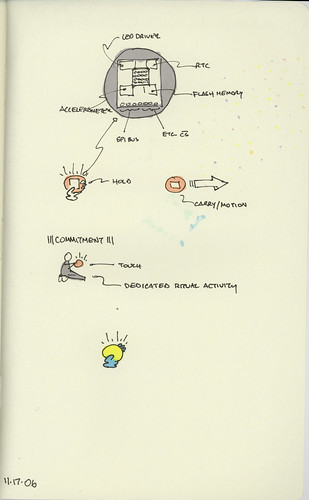

MobZombies is a baseline experiment because I’m actually somewhat more interested in how very broad movement can become an interface to what I imagine would be a very different kind of computing than what we have today. Broad as in extended gestures beyond semaphore antics. Why? I would like to re-interpret human activities as fodder for computational expression. But this requires shifting the general notion of what computation is, which will require more than words. It will require some designed objects that express this shift through perhaps what some will see as peculiar usage scenarios.

Why do this? Why shift what computing means? Part of that answer comes from a sense that there must be much more to what “computing can become” than smaller or faster or cheaper. But, specifically in this case, my reason for thinking and doing this is because of this thing that boggles me — that the interface for the instrument that dramatically refashioned the ways in which humans make culture — whether entertainment, leisure, maintaining and acquiring social relationships, waging war, circulating knowledge, knitting together the fabrics of societies — the whole smash..that interface is set up to make you sit down and punch little plastic squares..at best. At worst, just sit down and look at a screen. I mean..it feels incredibly protozoic. There must be something beyond that computing can become. Why hasn’t that next bit come to pass? Why is “computing” so instrumentalized and so sedentary in this way?

I like to think about an entirely revitalized notion of “mobile computing” that isn’t about a small phone with a relatively powerful computer on which you’re able to run spreadsheets while you’re out and about. I’m wondering about a kind of mobile computing that puts more emphasis on the “mobile” part of that framework, where motion, in the broadest sense, is the computational activity.

———————

1. Teresa, M. Possibilities for the digital baton as a general-purpose gestural interface CHI ’97 extended abstracts on Human factors in computing systems: looking to the future, ACM Press, Atlanta, Georgia, 1997.