An introduction and call for early adopters.

Ever since the slow death of Dopplr after its acquisition by Nokia a decade ago, the internet has lacked a dedicated space for people to casually share their travel intentions. Back in those days, it was also a feature of trip planning services like TripIt which since then pivoted to booking management for frequent flyers and real-time notifications when things go out of the route. With the ubiquity of smartphones, it made a lot of sense for social network platforms to propose services that focus on the instantaneous, the moments and the now. The fascination of the Big Now has been the major trend of the current version of the internet.

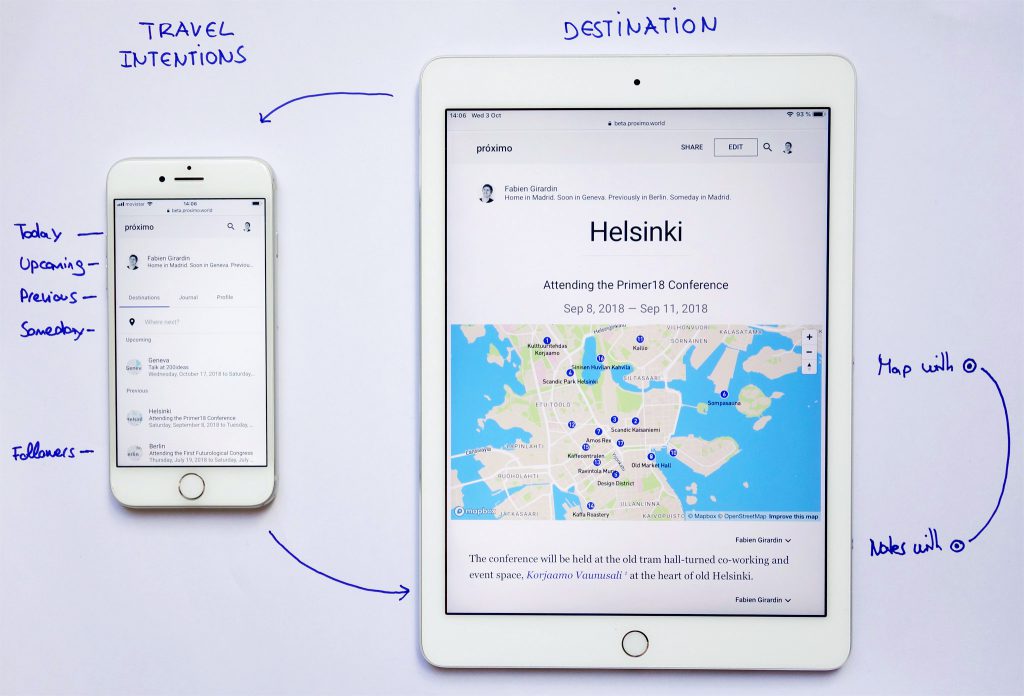

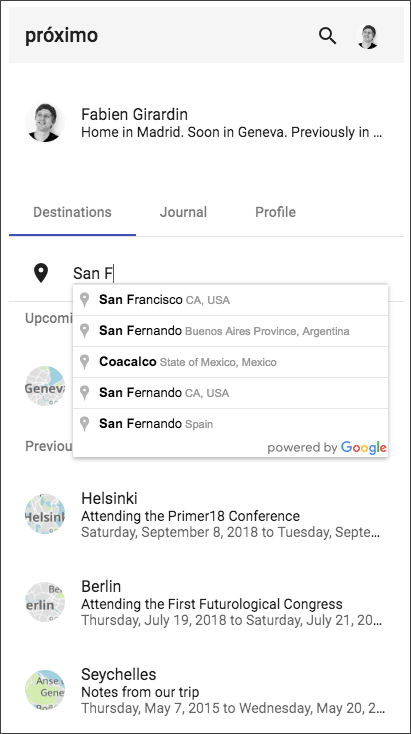

For some of us — regularly on the move — the practice of documenting familiar destinations and travel intentions demands its own casual and intimate space. This is what Próximo provides.

In consequence, I have observed people using multiple channels like emails, Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp to share their travel plans and request knowledge about destinations from their online contacts. And almost inevitably, I have noticed how that information would get lost in the noise of overfed inboxes or get buried within minutes under endless social media feeds.

Próximo: Thoughtful Words with Pretty Maps

For some of us — regularly on the move — that practice of documenting familiar destinations and travel intentions demands its own casual and intimate space. This is what my recent pet project Próximo provides and I need your help to figure out how it can better cover that need.

Próximo /ˈpɾoɡsimo/ means nearby and upcoming in Spanish. I have conceptualized, designed, developed and deployed it thinking about travelers who perform any of these habits: the record keepers, the connoisseurs and the prospectors.

Habit #1. The Record Keeper

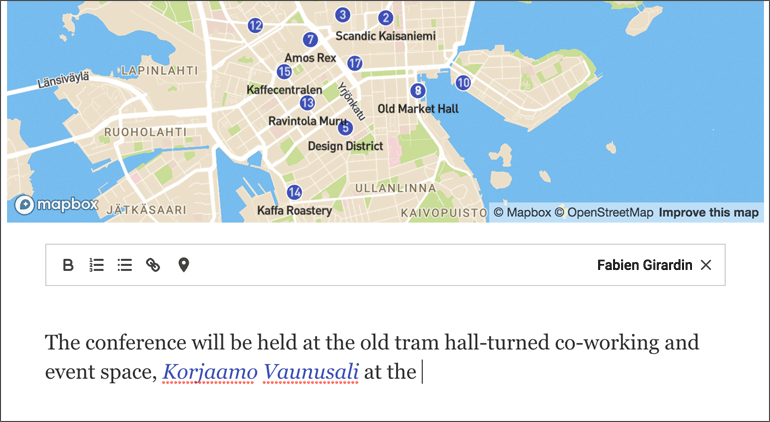

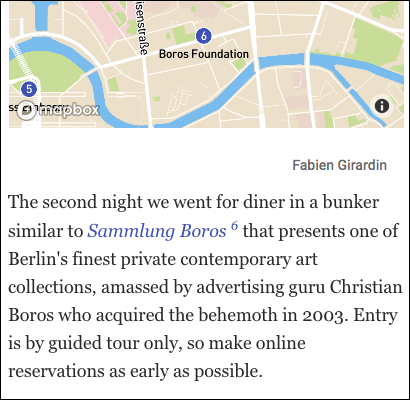

You regularly transform what you hear and see about destinations into reminders, notes or references. You have probably already tried Google Maps, Evernote or travel planning apps to organize them. Próximo offers a natural way to further support that practice. You can both provide context to your notes like in a travel guide AND easily map the relevant places.

Habit #2. The Connoisseur

You have good tastes and your friends, colleagues and family know that.You respond to email/social media requests for personal recommendation about the cities and destinations you are familiar with. In Próximo you can write brief notes tailored to your vegetarian coworker, his sister on her honeymoon, that shopaholic colleague, the foodie friend on a weekend wedding anniversary without her kids or a cousin on a business trip.

Habit #3. The Prospector

You ask around for ideas, suggestions or personal anecdotes to step away from the beaten path. You are also good at browsing the web for hours to spot that special sunrise place in Maui or that unique capsule hotel in Kyoto. In Próximo, you can keep notes of your research and invite friends to contribute with their thoughtful words, recommendations or stories based on who you are.

Call for Early Adopters

If any of these habits sound familiar and you feel intrigued, I invite you to try Próximo. Currently, it is web-based service hosted on proximo.world and you need a Google account to sign in.

It is built on the latest secure web frameworks and technologies (MEAN stack: MongoDB, Express, Angular, and NodeJS). You can delete your account at all time if you are not convinced or no longer want to use Próximo. Click the “Delete Account” in your “Profile” panel and all your data and texts will be deleted immediately.

Like an amateur painter I mainly create software like Próximo for myself. Keeping my hands dirty helps me think better as a professional. I am honored if a few people find the result compelling or inspiring. However, I never fall into the distraction that every idea must scale. This is human scale technology, built for a few, not the whole world. It is the best scale to learn.

I would love to hear from you or anybody you know who might be interested. Thanks for spreading the message. Feel free to comment or contact me.

At Near Future Laboratory we regularly engage into prototyping and envisioning exercises that explore how people negotiate their relation with time and space via digital technologies. For instance: Slow messenger, Humans, Memento, Omata and now Próximo.