Some quick notes on what we did last year.

* At Medialab Prado’s Interactivos 09 (“Garage Science”) in Madrid, the Laboratory contributed as an expert mentor for the fellows who were selected to develop their projects over the two week event.*

The socialization of technology and the accessibility of information available on the Web make it increasingly easy for anyone to have the possibility of building a home laboratory. Garage science is nothing new but home laboratories are connected now more than ever before. There are home laboratories of all kinds: technology factories, chemistry or biology labs, artists’ studios, places to rehearse, etc.

Interactivos 09 aims to explore these practices, where art, science and technology meet. We invite the participants to turn medialab into a garage laboratory where low-cost, accessible materials are used to develop objects and installations that combine software, hardware and biology. There’s license to fail!

Get the flash player here: http://www.adobe.com/flashplayer

var so = new SWFObject(“http://www.db798.com/pictobrowser.swf”, “PictoBrowser”, “530”, “480”, “8”, “#EEEEEE”); so.addVariable(“source”, “sets”); so.addVariable(“names”, “Interactivos 09 Madrid”); so.addVariable(“userName”, “julianbleecker”); so.addVariable(“userId”, “66854529@N00”); so.addVariable(“ids”, “72157613541285352”); so.addVariable(“titles”, “on”); so.addVariable(“displayNotes”, “on”); so.addVariable(“thumbAutoHide”, “off”); so.addVariable(“imageSize”, “medium”); so.addVariable(“vAlign”, “mid”); so.addVariable(“vertOffset”, “0”); so.addVariable(“colorHexVar”, “EEEEEE”); so.addVariable(“initialScale”, “off”); so.addVariable(“bgAlpha”, “90”); so.write(“PictoBrowser100101192811”);

* At Design Connexity, the 9th European Academy of Design conference held in Aberdeen Scotland, I was pleased to give one of the keynote addresses for that unique conference of designers working around the fringes of pretty much everything.

* I was asked to be Guest Editor and help curate this interesting event — Upload Cinema with their special edition on “Visions of a Future.” This was great fun as I’m fascinated by visual storytelling, especially ones that re-image the world, or the future. It also meant that I was to contribute some video introducing the event and, in the spirit of taking on too much, I had hoped to create a story within the story of 2001: A Space Odyssey with a bit of mistaken identity in which there is Hal, the custodian on the Odyssey who mistakes Bowman and Poole’s intentions to disconnect HAL as a discussion about firing Hal. Didn’t quite get it all together, but this is as far as I got (the night before the video was due..)

* I was graciously invited by Dave Gray to participate in Overlap 2009 held at Asilomar Conference Grounds. It was a brilliant hide-away to share and listen to some exceptional folks, discuss design and designing and workshop ideas with some great feedback and discussions. (And this also fulfilling — along with Design Connexity — participation in more events where I have no idea what to expect and I don’t know anyone!)

Get the flash player here: http://www.adobe.com/flashplayer

var so = new SWFObject(“http://www.db798.com/pictobrowser.swf”, “PictoBrowser”, “530”, “480”, “8”, “#EEEEEE”); so.addVariable(“source”, “sets”); so.addVariable(“names”, “Overlap 2009”); so.addVariable(“userName”, “julianbleecker”); so.addVariable(“userId”, “66854529@N00”); so.addVariable(“ids”, “72157621834134724”); so.addVariable(“titles”, “on”); so.addVariable(“displayNotes”, “on”); so.addVariable(“thumbAutoHide”, “off”); so.addVariable(“imageSize”, “medium”); so.addVariable(“vAlign”, “mid”); so.addVariable(“vertOffset”, “0”); so.addVariable(“colorHexVar”, “EEEEEE”); so.addVariable(“initialScale”, “off”); so.addVariable(“bgAlpha”, “90”); so.write(“PictoBrowser100102112453”);

* The Laboratory once again joined our friends who produce the O’Reilly ETech 2009 conference where I gave a short plenary on Design Fiction and again at Lift Asia held in Jeju, South Korea.

* The Laboratory visited John Marshall, Karl Daubmann and Max Shtein’s Smart Surfaces Studio at The University of Michigan, a collaborative, project-based learning experience in which artists, designers, architects and engineers come together to build physical systems and structural surfaces that have the capability to adapt to information and environmental conditions.

Get the flash player here: http://www.adobe.com/flashplayer

var so = new SWFObject(“http://www.db798.com/pictobrowser.swf”, “PictoBrowser”, “530”, “480”, “8”, “#EEEEEE”); so.addVariable(“source”, “sets”); so.addVariable(“names”, “Heliotropic Smart Surfaces”); so.addVariable(“userName”, “julianbleecker”); so.addVariable(“userId”, “66854529@N00”); so.addVariable(“ids”, “72157622508453535”); so.addVariable(“titles”, “on”); so.addVariable(“displayNotes”, “on”); so.addVariable(“thumbAutoHide”, “off”); so.addVariable(“imageSize”, “medium”); so.addVariable(“vAlign”, “mid”); so.addVariable(“vertOffset”, “0”); so.addVariable(“colorHexVar”, “EEEEEE”); so.addVariable(“initialScale”, “off”); so.addVariable(“bgAlpha”, “90”); so.write(“PictoBrowser100101192440”);

I was happy to give a couple of workshops and a lecture at the Fall 09 edition of Mobile Art & Code event at Carnegie Mellon University. (And, I got to write my first iPhone app — in a great 3 hour workshop!)

Get the flash player here: http://www.adobe.com/flashplayer

var so = new SWFObject(“http://www.db798.com/pictobrowser.swf”, “PictoBrowser”, “530”, “480”, “8”, “#EEEEEE”); so.addVariable(“source”, “sets”); so.addVariable(“names”, “Mobile Art & Code”); so.addVariable(“userName”, “julianbleecker”); so.addVariable(“userId”, “66854529@N00”); so.addVariable(“ids”, “72157622671312329”); so.addVariable(“titles”, “on”); so.addVariable(“displayNotes”, “on”); so.addVariable(“thumbAutoHide”, “off”); so.addVariable(“imageSize”, “medium”); so.addVariable(“vAlign”, “mid”); so.addVariable(“vertOffset”, “0”); so.addVariable(“colorHexVar”, “EEEEEE”); so.addVariable(“initialScale”, “off”); so.addVariable(“bgAlpha”, “90”); so.write(“PictoBrowser100101192132”);

* I gave a short talk at the New Industrial World Forum in Paris over the Thanksgiving weekend.

* I helped moderate and organize the Mobile Media event at UCLA’s Design Media Arts. (Here are some videos from the event)

Get the flash player here: http://www.adobe.com/flashplayer

var so = new SWFObject(“http://www.db798.com/pictobrowser.swf”, “PictoBrowser”, “530”, “480”, “8”, “#EEEEEE”); so.addVariable(“source”, “sets”); so.addVariable(“names”, “UCLA Mobile Media Symposium”); so.addVariable(“userName”, “julianbleecker”); so.addVariable(“userId”, “66854529@N00”); so.addVariable(“ids”, “72157622719166059”); so.addVariable(“titles”, “on”); so.addVariable(“displayNotes”, “on”); so.addVariable(“thumbAutoHide”, “off”); so.addVariable(“imageSize”, “medium”); so.addVariable(“vAlign”, “mid”); so.addVariable(“vertOffset”, “0”); so.addVariable(“colorHexVar”, “EEEEEE”); so.addVariable(“initialScale”, “off”); so.addVariable(“bgAlpha”, “90”); so.write(“PictoBrowser100101192021”);

* At the studio I work at at Nokia, I led Project Trust, which was challenging in a good way with exceptional outcomes from an exceptionally professional and brilliant team. I continued to learn to model in 3D, although not as much as I would have liked (..I have yet to get on the CNC machines.) As J-B reminded me, there was less electronics design, and more design design. Which is not necessarily bad, but something to be mindful of so as to not loose that edge.

* The “Booklet 3G” launched, which was one conclusion to work that the entire studio participated in led by Duncan and Tom and that took a curious route around and about that reveals quite a bit about how design works when the linkages of accounting, engineering, business strategy and time all attempt to articulate the one amongst the others. This, to me, was exciting in a simple, perhaps naive way. It’s intriguing to watch the way ideas, ownership and the stakes of something like this knock about. (I’m not trying to be snarky — this is good work; I’ve just never participated in good work amongst hundreds of other people. A real experience in how things happen in a big organization.)

Get the flash player here: http://www.adobe.com/flashplayer

var so = new SWFObject(“http://www.db798.com/pictobrowser.swf”, “PictoBrowser”, “530”, “480”, “8”, “#EEEEEE”); so.addVariable(“source”, “sets”); so.addVariable(“names”, “Booklet 3G”); so.addVariable(“userName”, “nearfuturelab”); so.addVariable(“userId”, “73737423@N00”); so.addVariable(“ids”, “72157623123054192”); so.addVariable(“titles”, “on”); so.addVariable(“displayNotes”, “on”); so.addVariable(“thumbAutoHide”, “off”); so.addVariable(“imageSize”, “medium”); so.addVariable(“vAlign”, “mid”); so.addVariable(“vertOffset”, “0”); so.addVariable(“colorHexVar”, “EEEEEE”); so.addVariable(“initialScale”, “off”); so.addVariable(“bgAlpha”, “90”); so.write(“PictoBrowser100102123712”);

* The Laboratory completed the first part of a three part project on the topic of Design Fiction, which will continue into this year.

* Nicolas Nova and I co-wrote A synchronicity: Design Fictions for Asynchronous Urban Computing with the fine folks at Situated Technologies, the Center for Virtual Architecture, The Institute for Distributed Creativity and The Architecture League. It is a discussion between the two us from the Situated Technologies Pamphlets series, published by the Architectural League. This series aims at exploring the implications of ubiquitous computing for architecture and urbanism: How are our experience of the city and the choices we make in it affected by mobile communications, pervasive media, ambient informatics and other “situated” technologies? How will the ability to design increasingly responsive environments alter the way architects conceive of space? What do architects need to know about urban computing and what do technologists need to know about cities?

* Pole Cam — we continued to experiment with projecting other points of view through cameras mounted on really tall poles. This was a curious probe into the possibilities of visual metaphors for understanding subtle and complicated experiences, both empirical and theoretical.

* We continued some experiments in generative and parametric mapping, creating topo maps based on my occupancy of Southern California. The experiments continue.

Get the flash player here: http://www.adobe.com/flashplayer

var so = new SWFObject(“http://www.db798.com/pictobrowser.swf”, “PictoBrowser”, “530”, “480”, “8”, “#EEEEEE”); so.addVariable(“source”, “sets”); so.addVariable(“names”, “LA Generative Procedural Maps”); so.addVariable(“userName”, “nearfuturelab”); so.addVariable(“userId”, “73737423@N00”); so.addVariable(“ids”, “72157622074827670”); so.addVariable(“titles”, “on”); so.addVariable(“displayNotes”, “on”); so.addVariable(“thumbAutoHide”, “off”); so.addVariable(“imageSize”, “medium”); so.addVariable(“vAlign”, “mid”); so.addVariable(“vertOffset”, “0”); so.addVariable(“colorHexVar”, “EEEEEE”); so.addVariable(“initialScale”, “off”); so.addVariable(“bgAlpha”, “90”); so.write(“PictoBrowser100102124912”);

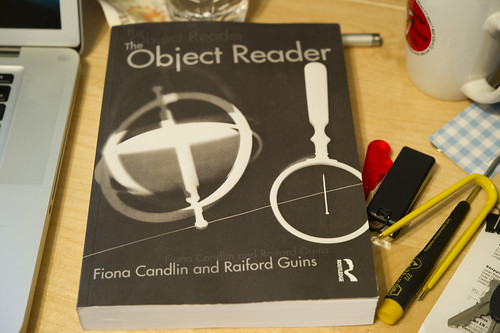

* The essay from 2006, A Manifesto for Networked Objects (Why Things Matter) was reprinted in the splendid compilation The Object Reader edited by Fiona Candlin and Raiford Guins.

edited by Fiona Candlin and Raiford Guins.

Those are the highlights that come to mind. Now, 2010.

Continue reading The Year Ending 311209

— a middling accomplishment in the shadow of 2001, but more of a movie than the cinephile’s 2001, at least insofar as one might measure the distinction using the vulgar calculus of *words-of-dialogue-per-film-minute.*