In order to produce anything, you need three elements: an idea, the means to make the idea, and the money to pay all concerned. For these reasons it comes as no surprise that the entrepreneurial explosion of the early 2000's has focussed on software. Once the idea is solidified, the manufacturing and shipping of a software product, whilst not exactly simple is at least attainable by a small number of people with basic equipment and minimal outlay. In the world of object production the idea is the least of your worries. Atoms, as it has been said many times before, are difficult to wrangle, the engineering infrastructure, commitment level and financial outlay is significant. Even for a tiny plastic widget the initial tooling can run into many thousands of dollars. There's a change afoot in the world of atom wrangling however, and it's name is 3D printing.

I saw my first 3D printer whilst working at Dyson in the 90's. I remember it very clearly. The workshop acquired a 3D printing machine which arrived to great fanfare and was duly installed into it's own dedicated room, similar to an early computing system. A modelmaking technician was assigned and he undertook a lengthy programming and maintenance course. The machine was a Fused Deposition Modeller (FDM) which functioned by squeezing a thin bead of plastic around a pathway, then moving up a tiny amount and producing the next layer. By contemporary standards the models took an age to make, and due to the FDM process the models were very wobbly. Dyson still employed a permanent team of modelmakers to fill, sand and paint the parts to make them suitable for use. Fast forward to 2001. I was working at London design consultancy Seymourpowell when I used my first stereolithography (SLA) part. It cost a fortune, we had to contact an outside agent to produce it, and it took two or three days to arrive. We wore gloves to prevent the moisture in our fingers from warping the part, and it was so fragile we moved it around the model shop like a piece of fine china. Fast forward again to today. In our studio we have a couple of 3D printers, one prints out a wax-like substance and the other prints in full color onto a bed of what looks like talcum powder. A standard phone-sized part takes about an hour to make and and hour to dry and treat. We now print things out every few days or so, and (pretty much) don't think about the cost.

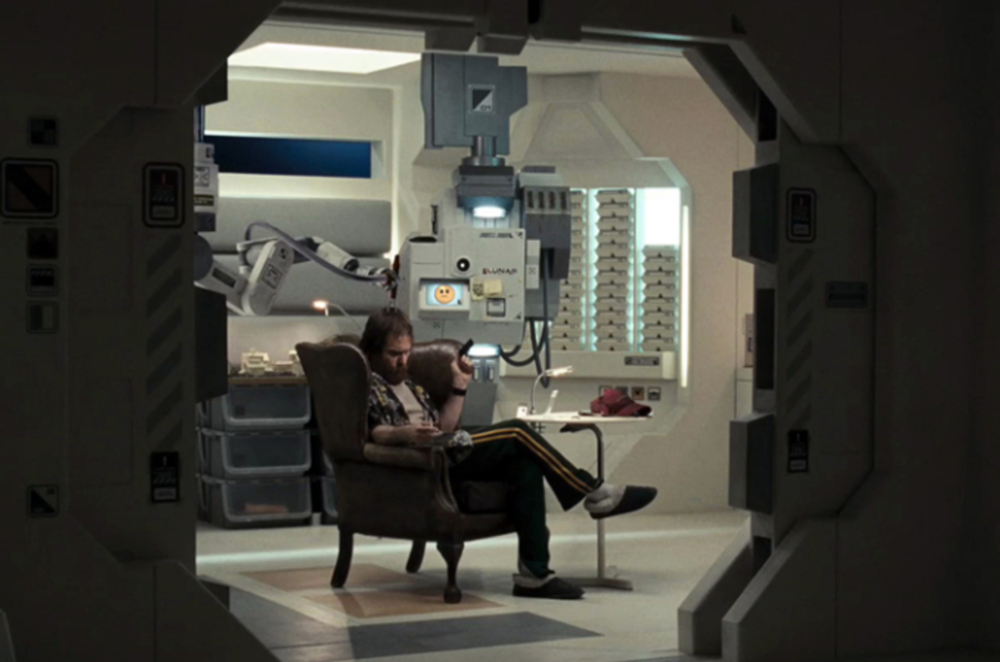

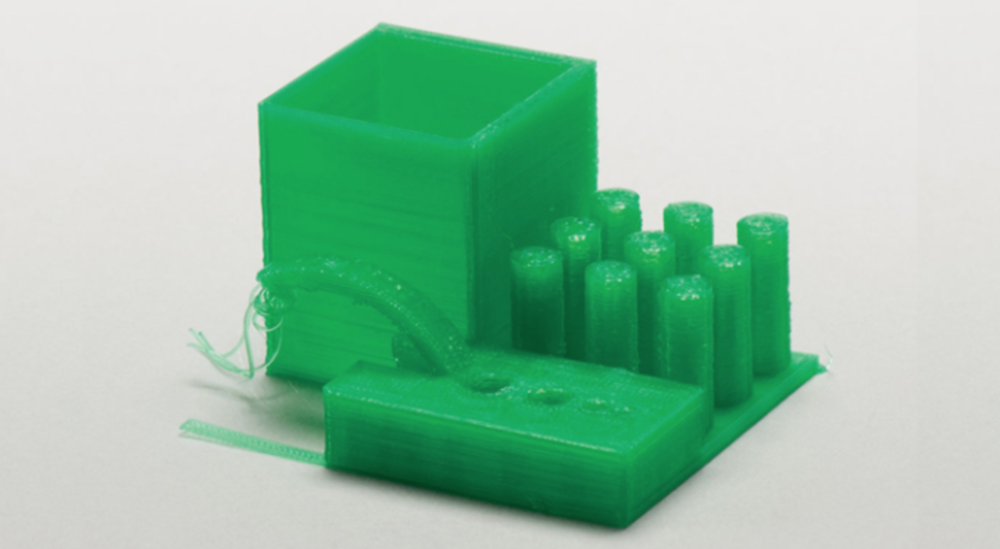

Things have changed in the world of 3D printing in a relatively short space of time, thanks in part to a small group of entrepreneurs led by Bre Pettis. His company, Makerbot Industries was founded in Brooklyn NY in January 2009 with the lofty aim of bringing 3D printing into the homes of regular folks. They currently produce the Replicator 2, a fairly primitive version of the FDM machine I first used at Dyson. Small, monochrome objects can be produced via these machines, building layer upon layer of plastic 'toothpaste' to produce a coherent whole. The finished products look a little like this:

To the industrial design community the objects and machines are seen as primitive, but in the public sphere they have captured the collective imagination. Barack Obama even referred to the process in his 2013 State of the Union address:

“A once-shuttered warehouse is now a state-of-the art lab where new workers are mastering the 3D printing that has the potential to revolutionize the way we make almost everything."

This is one of those rare moments where the world of design and manufacturing breaks into popular culture. I have rarely seen such ebullient and effusive journalism, from the highest and most trusted sources. I suggest you read a few of the articles is listed below, in order to get a grip on just how this technology is portrayed.

Harvard Business Review 3D printing will change the world

Forbes Will 3D printing change the world?

New York Times On the fast track to 3D printing

The Guardian 3D printers shape up to lead the next technology gold rush

There's even an entire magazine dedicated to the subject.

In reading these articles we could be forgiven for believing we are in the midst of a genuine revolution, a wholesale change to the way in which products are conceived, created, and consumed. As such, I suggest we take a little time to view this technology objectively, which I aim to do here. The 3D printing revolution seems to hold three tenets to be true.

Tenet 1: items can be produced quickly In the world of Industrial Design, there's a reason why 3D prints are regularly referred to 'rapid prototypes'. Compared to the timescales involved with traditional model making, 3D printers are able to generate a solid approximation of the desired form with amazing pace. Time from CAD to 'thing in the hand' is very quick, comparatively. However, this notion of 'rapid' seems to have caused some confusion in journalists and has been reappropriated to represent not prototyping but manufacturing.

In the world of manufactured objects, heated plastic is pushed, pulled, inflated and squeezed into tools to produce everything from bottles to cellphones. The most popular form of plastic manufacturing is injection molding. When compared to the entire cycle time of injection molding (including tooling, polishing, injection and cooling) the 3D printer is indeed quicker, but once the injection tool is finished, there's just no contest. Cycle times for industrialised injection molding machines can be lower than a second, and if you want to produce anything at scale it's still the only sensible choice. We should also talk about quality, as it's no good just producing an object, it needs to be produced with integrity. In a world populated by iphones and BMW's a 3D printed object just doesn't have the aesthetic oomph required to compete. Structural integrity is also significantly sub par, the lack of an internal homogenous crystal structure means 3D printed parts are brittle and unstable. When comparing speeds, we need to be very careful that we're comparing like with like, and it's unfair to put to both techniques in the same category. 3D printed parts may be produced 'quickly' when compared end-to-end with injection molding, but at commercial scale they fail on almost every level.

Tenet 2: a user can print whatever they want This is perhaps the most potent promise of 3D printing - empowering individuals as makers through the democratization of manufacturing tools. (There is a larger 'maker movement' behind this promise, borne from numerous hacking, artisanal and fixing communities, which we may delve into at a future date). The freedom created by 3D printing is not limitless though, and whilst Obama refers to 'almost everything' we should take time to understand the true parameters of this technology.

Firstly, current 3D printers are bounded by their space envelope. The Replicator 2 can print objects of 28.5 x 15.3 x 15.5 cm. There are larger devices, but typically the print volumes are around that of a microwave oven. Anything larger needs to be made in pieces and connected afterwards by bonding parts or mechanical joints. Secondly, 3D printers typically produce objects from polymers. There are advances in metal 3D printing but these are fairly limited (a quick look at '3D printed metal' as described on the Shapeways site will give you an idea how complicated the process is). Thirdly, products such as the Makerbot can only print one colour at a time, this can be changed but a new colored filament needs to be threaded into the machine for each color break. Other printers can produce a wider variety of colors, but the resolution and vibrancy is pretty poor. Also, every part produced in a 3D printer has a rough, matte surface, which needs sanding and painting if gloss is desired.

So if our definition of 'whatever' fits those material, finish and volumetric constraints, we then need to ask the question about where the 3D data comes from.

In industry, 3D objects are created with software such as Catia, Alias, ProE, or Solidworks. These are very complex and involved software packages which take years to master. Recently we have seen a growth in consumer focussed software such as Rhino or Google Sketchup, whilst these are simpler they still require a level of understanding, and the data they output is fairly primitive. There are improvements in 3D scanning (a natural partner to 3D printing) which uses laser arrays to create a 3D model for replication purposes, but the devices are expensive, complex and produce data which still needs cleaning and modifying in a conventional 3D CAD package.

So if the thing you want to make doesn't need to be aesthetically driven, fits into the printer bed and you have the requisite 3d CAD skills, what are you going to make? Herein lies the largest question. There are four primary business models which have emerged from the primordial soup of 3D printing:

1. data made at home, printed at home. This is the realm of the tinkerer, the maker, the hobbyist. As a totally non-scientific example of the sorts of things we're talking about, take a look at Brendan Dawes tumblr, which I feel is fairly indicative. This group typically makes two types of object: the art piece or novelty, or the specialised functional addition. As a tool for the individual maker, a 3D printer is very exciting. In this model, the 3D printer sits in the same space as any hand manufacturing technology, from carpentry to welding. I think this is where 3D printing has a significant future. Allowing people to make fun little things for themselves, or fix a little doohickey is perfect. That's the DIY fixer mentality, and I like it.

2. data made at home, printed elsewhere. This is an interesting development which could have only occured in this networked age. If you have the ability to produce 3D data, but do not have the desire or opportunity to buy a 3D printer, then someone else can print it for you. Simply upload your data to a service like Shapeways, or send it to a local model shop, and in a few days you can have the part you need. This is no different to subcontracting to a local modelshop or machinist, but within this model comes a shift. If you make a part and think others will find it useful, you are able to sell the data for others to download and acquire prints for themselves. You shift from being a maker to a manufacturer and move into the third and fourth business models:

3 & 4. data made elsewhere, printed at home / data made elsewhere, printed elsewhere. Services such as Shapeways (there are others) allow people to download data and build their own object, or acquire the object directly just like any other store. The promise of millions of entrepreneurial designers now having an on-demand manufacturing and retail service is enticing indeed, but the shift between these business models is significant and troubling.

The joy of 3D printing is it bypasses homogeneity, you no longer need to ensure a market volume before committing money to tooling. One of the main reasons for homogeneity in mass production is consistency. Consistency is present in mass production for lots of reasons, commercial and capitialist ones come high on the list, but homogeneity also ensures that every user gets the same object. It's clear that the current regulatory framework around manufactured objects is crippling the industry, and I won't defend it in it's entirety, but we must remember that these systems are in place to protect people. The CE mark, the Kite mark, the double insulation standards and the FCC mark are rigourous and complicated systems of conformity which ensure that manufacturers pay due care and attention to protecting the consumer from harm during use. Correct certification and indemnity also protect makers from litigation, and offers a tried and tested procedure for investigating genuine faults. These systems are laborious and onerous, but they help. 3D printing is in it's infancy and most products are bought in good faith to support a kickstarter project or maker, but that's not good enough. Shapeways has a paragraph in its T&C which states:

"PLEASE NOTE THAT THE MATERIALS WE USE FOR MANUFACTURING THE MODELS MAKE THE MODELS SUITABLE ONLY FOR DECORATIVE PURPOSES AND THEY ARE NOT SUITED FOR ANY OTHER PURPOSE. THE MODELS ARE NOT SUITED TO BE USED AS TOYS, TO BE GIVEN TO CHILDREN. THE MODELS SHOULD NOT COME IN CONTACT WITH ELECTRICITY OR FOOD OR LIQUIDS AND SHOULD BE KEPT AWAY FROM HEAT"

Makerbot's comparable website Thingiverse has a similar clause:

"WE (AND OUR SUPPLIERS) EXPRESSLY DISCLAIM ANY WARRANTIES AND CONDITIONS OF ANY KIND, WHETHER EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING THE WARRANTIES OR CONDITIONS OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, TITLE, QUIET ENJOYMENT, ACCURACY, OR NON-INFRINGEMENT."

This hands-off approach to culpability cannot last long. If you design something to go into someone's bathroom, it will make it's way into their childs mouth. If someone buys, downloads and prints a case for their OUYA and they suffer an electric shock as a result, who is to blame? If a person replaces their phone case with a 3D printed one, and it doesn't survive a drop to the floor, what then? We need to create a new chain of responsiblity for this emerging, and potentially very profitable business.

When people want to print cases for their Raspberry Pi it's smiles all round, but the questions raised by the heavily publicized ambitions of Cody R Wilson to 3D print gun parts through his DEFCAD site have opened the debate about what type of objects are printed as opposed to the quality thereof. Whilst I understand that 3D gun parts could be cause for concern, I think they are inevitable. We need to understand that if we make the tools available, people will use them. The early days of desktop publishing saw calls from professional graphic design associations for the registration and licensing of desktop printers, in an attempt to curb a rising tide of 'bad design'. This type of regulation was obviously impossible to enforce but we're seeing similar efforts by lobbyists and the makers of 3D printers. In a strange puritanical brand protection exercise, Cody Wilson recently had his personal 3D printer repossessed by Stratasys for printing the lower receiver of an AR15 assault rifle. Gun parts fall right at the end of the bell curve, but if we allow people to make anything, then they will make everything. We will find it impossible to regulate what constitutes an 'acceptable' or 'unacceptable' part sooner than we think, but let me leave this section by asking the following question: is a right wing crypto-anarchist distributing weapons data any more dangerous than unregulated, uncertified printed plastic parts finding their way into our offices, homes, cars and kitchens?

Tenet 3: that by producing products at the market we can reduce environmental damage

The story unfolds thus: if we only print what we need, if we produce objects at the source and cut out the shipping, if we allow people to mend rather than buy new, 3D printing will have a significant positive impact on the environmental footprint of manufacturing. If we feel that allowing individuals to produce their own plastic parts will in any way reduce the impact of manufacturing on the environment we are kidding ourselves. Allow people to print plastic and that's what they will do. A LOT. A quick look at the Shapeways catalog tells you what people want to print. It's not replacements for existing parts, it's just more stuff. Plastic furniture for their dolls house, plastic bottle openers, plastic stands for their ipad, plastic bracelets, even TINY PLASTIC VERSIONS OF THEMSELVES. Implying that individuals will in some way help reduce plastic use by only printing what they need is naive indeed. As they say at Forbes: "Why settle for wearing the same glasses every day when you can print a new pair to suit your mood?". 3D printing may cut out the shipping element which may have a slight environmental plus, but the plastic still needs to be shipped to your house in spools. The waste produced in the manufacture of 3D printed parts can be significant, and often toxic. We also shouldn't forget that designers and mass manufacturers have many years of experience in the most environmentally approriate construction of plastic parts, and are regulated along similar lines. I believe in the power of 3D printing to fix problems or revive a broken product, and have used it to this effect myself. This is a good promise, but a very small section of society thinks in this way, and have the requisite ability and access to be significant.

Evolving 3D printing

My aim with this piece of writing is to open the counter argument to what is currently a very one-sided debate. The topic is here to stay, so we need to tear off the rose tints and understand it in it's entirety. Let me conclude with some key changes and developments I see in the future of 3D printing:

a) 3D printers will get better. As we have seen there is keen interest in 3D printing, which will drive down cost and make the service more ubiquitous. For reference, there is already a 3D printer available in the Skymall catalog. In parallel, the quality will improve with new materials, better finishes and higher speeds. A clear parallel to this comes in the form of domestic laser printers, a technology which has improved in quality and decreased in cost at a rate which seemed impossible only years before. In parallel, the 3D CAD software will become simpler and cheaper, making the original data easier to create, just as blogging tools have done for coding.

b) We need regulation. Before you get all excited by my use of the word 'regulation' I use it cautiously. Whilst I agree that the very spirit of independent manufacture runs counter to the slow lumbering legal system, there needs to be some thought in this area. Once we move away from buying 3D printed parts to support a friend or Kickstarter project, once we stop seeing the objects as craft, we need to move into the world of true manufacturing and accept the responsibility that comes with it. We are undoubtedly in the Wild West era of 3D printing, but I think it's right and proper that we question a system where an individual can make significant income from the sale of a part and have utterly no responsibility for the safety of the person buying it, or accountability for quality or environmental impact. Current regulatory systems are not suited to this type of manufacture but I feel we need to create a new framework for certification. I welcome any ideas to the debate.

c) Emerging business models. I see 3D printing finding a home where it is currently most popular - as a prototyping tool and a hobbyist device. I'm not hugely swayed by the argument for widespread domestic 3D printing, at least not yet. We haven't found a compelling use for such machines at a mass scale. I'm keen to see how companies such as Shapeways grow, how the balance between data sales, object sales and printing services shifts, that will be most telling. 3D printing will also expand out of the middle class hobbyist environment into low income rural spaces, warzones or developing countries. Perhaps then we will see something more interesting than a scanned bust of someones head.

d) Response of big business. So what about all those huge corporations who currently spend billions on injection molding and shipping in bulk? In big business 3D printing is now referred to as 'additive manufacture' and many millions of dollars are being spent investigating the area. There are a few hindrances to a mass manufactured device which uses additive manufacture, namely time, finish, quality and material choice. 3D printing will most likely find it's first commercial success not as a cosmetic part, but as an internal assembly. The benefit of additive manufacture is that it negates any requirements for complicated cores or tooling, making it more suitable than injection molding for complex assemblies. In parallel we can expect the integration of components into a 3D print rather than post assembly, which would again point at an internal use. Once 3D printing finds it's 'killer app' it will seem entirely natural, but we're still looking.

Outside of a manufacturing shift, 3D printing also has the requisite futuristic cachet to make it attractive to advertisers and promotions. We may see it used as a direct mail or commercial outlet, just as we did with faxes towards the end of their widespread use. Ford could send you a little model of the new F150 for you to fondle and swoon over. Customers could print out approximations of objects to see how they look before we commit to an online purchase. Manufacturers may make more of their data open source to encourage and engage with the 3D printing community (just as Nokia recently did), adding customisation and personalisation options to a mass manufactured item. In parallel to individual regulation we also need to see how big business defends their patents and trademarks in an era where an accurate facsimile of a product can be independently produced. Perhaps we will see 3D watermarks or form recognition algorithms to prevent counterfeiting, just as Xerox machines can recognize and prevent the copying of currency. Big manufacturing doesn't run counter to the 3D printing revolution, it just has it's own uses for it.

e) improved quality of one off and batch production. We should also remember that in the world of made things, there are still very lucrative businesses which produce parts in low quantities. From aerospace, motor racing, and hollywood, to jewelers, architects and the medical sector, we will see increased use of 3D prints as a step in the prototyping process or as functional, usable parts.

It's my firm belief that 3D printing is here to stay, but exactly how it stays and for how long is the bigger question. As designers of the future we have a responsibility to embrace new making, but we should ensure that we aren't swept along with the hype. There are big questions to be asked about this technology and it's our job to ask them. I would love to build on this debate further, and will keep the comments section open.