My interest in design fiction has always been related to my ethnographic practice (see for instance this piece about it) which is why I find it interesting to run into these two notions :

"Ethnographies of the possible", coined by Joachim Halse (2013):

"are a way of materializing ideas, concerns and speculations through committed ethnographic attention to the people potentially affected by them. It is about crafting accounts that link the imagination to its material forms. And it is about creating artifacts that allow participants to revitalize their pasts, reflect upon the present, and extrapolate into possible futures. These ambitions lie at the borderland between design and anthropology. For designers involved in this type of process, it is a new challenge to craft not beautiful and convincing artifacts, but evocative and open-ended materials for further experimentation in collaboration with non-designers. For anthropologists, it is a new challenge to creatively set the scene for a distorted here and now with a particular direction as a first, but important step toward exploring particular imaginative horizons in concrete ways."

Halse, J. (2013). "Ethnographies of the possible", in Gunn, W., Otto, T. & Smith, R.C. (eds). Design Anthropology: Theory and Practice, Bloomsbury, pp. 180-196.

"Anticipatory ethnography", proposed by Lindley and Sharma:

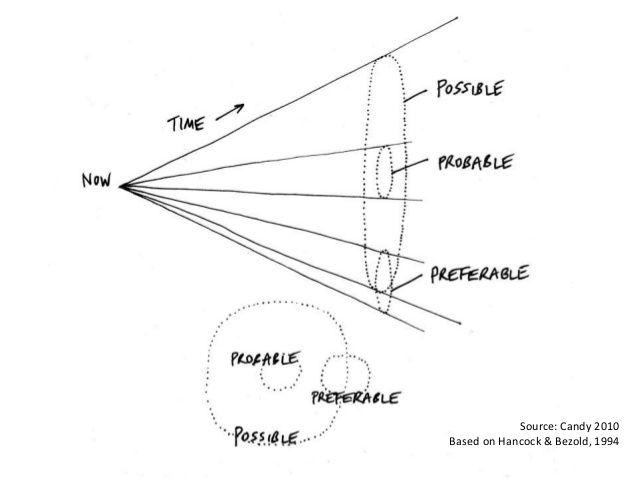

"Anticipatory ethnography suggests that the properties of the traditional inputs to design ethnography (situated observations) are analogous with the ‘value adding’ element of design fictions (diegetic prototypes). [...] Assuming that these suppositions are correct, then we can infer that combining the exploratory and temporally independent techniques of design fiction, may allow design ethnography to glimpse the future. Conversely, design ethnography’s established tools for sense making and analysis can be applied to explorations in design fiction. Can anticipatory ethnography lend speculative, the gravitas of hindsight?"

Lindley, J. & Sharma, D. (2014). An Ethnography of the Future. Paper presented at ‘Strangers in Strange Lands’ – An anthropology and science fiction symposium hosted by the University of Kent, Canterbury.

Why do I blog this? These definitions echo with my own research interests. More specifically, a project like Curious Rituals is based on a dual movement : a field research phase that aimed at designing a fictional representation of everyday gestures with digital technologies. To some extent, it is close to the two concepts defined above... and I see design fiction as a sort of "downstream user research" approach to test scenarios about the future... for instance by running focus groups with users and project stakeholders, generating a debate about pieces of technologies by taking concrete instances/scenarios (videos, catalogues, user manuals, etc.).

These definition also reminded me of Laura Forlano's text on Ethnography Matters. Called "Ethnographies from the Future: What can ethnographers learn from science fiction and speculative design?", it dealt with similar issues and ended up with this insightful remark:

"As ethnographers, it is not enough to describe social reality, to end a project when the last transcripts and field notes have been analyzed and written up. We must find new ways to engage and collaborate with our subjects (both human and nonhuman). We need better ways of turning our descriptive, analytical accounts into those that are prescriptive, and which have greater import in society and policy. We may do this by inhabiting narratives, generating artifacts to think with and engaging more explicitly with the people formerly known as our “informants” as well as with the public at large."