Yesterday François Bar came by the design studio to chat. He offered a perspective on a technology that made it impossible to believe the instrumentalists perspective. What we off-handedly refer to as “technology” is always about social institutions and cultural practices and never any less. It is no more “neutral” and outside of their participation in sometimes fierce institutional politics and debates than the spotted owl. Or, more recently, the Pacific Salmon just off the coast here on the west coast who have had a temporary reprieve in the form of a ban on their being fished in order to conserve their dwindling population. (I counted four government organizations, a couple of professional associations, a few concerned fishermen and three state’s governors who have taken the time to make the Pacific Salmon a political partner.)

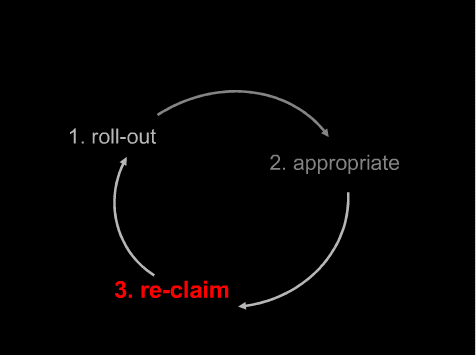

I came away from the talk thinking about design as a “conversation” — one amongst the sanctioned designers, often trying to articulate an immaterial idea and make it material. Designers who have consumed this materialization and refashion it — sometimes subtly, other times, as shown in the IED detonator above, with mortal consequences. And this refashioning — what François describes as appropriation/cannabilism — can often be “re-claimed” by the sanctioned, professional designers and iterated upon again. This final iteration may take into account the appropriation and adapt it. It may also co-opt it, or block it entirely. And the cycle continues in this way.

This image was presented in François’ talk and has been around it seems for a couple of years. For me, it stood in for a couple of things. First, is what is most direct. The re-use / appropriation to create a bomb. And that is what most people will see, and the reaction quickly moves to one that says — see? all technologies are just neutral and it is only in their use that we can discuss them, which can be good (call mom to wish her a happy birthday) or evil (use it to detonate an IED.) (This, just to be pedantic, is nonsense. Technologies are only ever used in a social practice and so never neutral in this sense.) What is less directly captured in this image is the notion of cannibalism. Not the physical tearing apart of the device to turn it into a trigger, but the consumption of power that the bomb maker undertakes materially and metaphorically. This power or capability to do “something” is what is already in the device and is the reason why consumers “consume” mobile phones. Things to be consumed are aspirational in that they present a new sort of power — a new super power, that is beyond what one has already. It may be consumption to create status for oneself, as François described. The Brazilian Tupi consumed their enemies — sometimes Bishops arriving to colonize, sometimes Tupi enemies from other tribes.

Cannibalism is an exemplary mode of consumerism adopted by under-developed peoples. In particular, the Brazilian Indians, immediately after having been “discovered” by the first colonizers, had the rare opportunity of selecting their Portuguese-supplied bishop, Dom Pedro Fernandes Sardinha, whom they devoured in a memorable meal.

(Cf Cannibal Manifesto by Oswald De Andrade, 1930.)

François’ talk was titled Mobile technology appropriation in a distant mirror: baroque infiltration, creolization and cannibalism. It was a fascinating perspective on the ways in which Brazilian culture is one of appropriation and what, today, we’d call remix. Historically this was in a form that we’d grotesquely call cannibalism but which, I have to believe, was not so much a savage activity as it was a complex ritual of consuming the power and spirit of those who were eaten.

François outlined three appropriation modes: baroquization, creolization and cannibalism. Baroquization refers to the cooperative way in which churches were adorned with hybrid sculptures and engravings that were a mix of traditional colonial styles of christianity and local symbols, such as tropical fruits or tropical bird feathers. Creolization refers to mixes of European (colonizer) and black cultures that was what derived from colonization. He gave the example of musical styles that mix creole rhythms with classical European melodies. Cannibalism refers to the practice of eating the bodies of others to assume their power.

This to me gave a direct explication of appropriation in this particular context. It was much more sophisticated and sensible than vague descriptions — because it gave particular instances in a specific cultural context. (Which is hard work, and which takes time because you have to look at local contexts and not make broad assumptions from your easy chair.)

He gave examples from Brazilian and some larger South American contexts about such things as m-banking and how it starts in a simple fashion (roll-out), becomes appropriated to meet the specific needs of some communities and then is “re-claimed” as he refers to it and re-deployed as a commercial entity.

1. Roll-Out / 2. Appropriate / 3. Re-Claim

The “reclamation” modes he described are: co-opt, adapt and block. These are the typical modes by which an owner (corporation) might look at how their technological-practice framework (a device or a service instrumented by devices, for example) has been “consumed” or, in a more indelicate description, cannibalized, by people who have decided that the framework is desirable — its power to effect some kind of material or ephemeral change in their lives, however simple or complex, is something useful or perhaps necessary for them. So — they “buy in.” They consume it.

Sometimes, it gets cannibalized. Sometimes it tips over and becomes something else.

This cycle was the most intriguing part of the discussion. It got me thinking about the cycle as a kind of conversation (to sound polite and open to discussion) amongst designers — both those who sanction themselves as designers (industrial designers, product designers, business strategists in some sense, etc.) within companies, and people — “consumers” who designers, effectively, colonize with their wares. Sometimes that “conversation” is quite terse — EUA’s explicitly circumscribe what sort of consumption a consumer may engage in. Cannibalism is almost strictly forbidden as a matter of law.

What are the implications this perspective has on design in the first instance? It’s more than open technical systems, I think. Only a small group of people find the gumption to tackle hardware and software systems — it’s quite sophisticated work, generally speaking. There’s a middle ground somewhere to be explored. One that makes technology-practice frameworks amenable to appropriation/cannibalism without “killing” the designer in the first place.

Technorati Tags: design, Design, consumption