Most connected humans suffer from poor ‘data hygiene’. For instance, we are plainly grotesquely overfed on social media with its ‘anytime’ ‘anywhere’ experience and there is no rational end in sight. In this article, I introduce the reasons why I developed Humans, an app that offers a way to rationally manage too many social media contacts and slows down the consumption of status updates, tweets, selfies, and photos of all kinds.

We live in a society that captures the moment, refashions it to ‘share’ across a network of social media endpoints containing algorithms and human, perpetually. Social media, its algorithms and its humans are highly optimized to never stop the cycle. Consequently, we experiencing an unprecedented increase in the rate of this ‘anytime’ ‘anywhere’ consumption cycle. As of 2014, according to the Nielsen US Digital Consumer Report almost half (47%) of smartphone owners visited social networks every day. On top of that, it is not uncommon for a Facebook user to have 1,500 posts waiting in the queue when logging in. Yet, the perpetual consumption yields to very little and there is no rational end in sight. We are quite plainly grotesquely overfed on social media.

Social media needs its consumption cycle. It depends on ‘views’, ‘eyeballs’, ‘reshares’, ‘likes’, ‘comments’ — the euphemism used by the media mavens is the optimistic word ‘engagement’. We are bloated on ‘engagement’ to the point where we sleep with our nodes, wear them on our wrists, clip them to our dashboards, autistically shove them in pockets only to immediately remove them only to shove them back in our pockets only to immediately remove them in order to slake our thirst for more content. This ‘too much, too fast’ consumption cycles has reduced an ability to pay sustained attention, have a meaningful conversation, reflect deeply — even be without our connected devices.

Humans create technologies, adapt their behaviors to them and vice-versa

The fact is that each major revolution in information technology produced descriptions of humans drowning in information unable to face tsunamis of texts, sounds, images or videos. For instance, in the 15th century Gutenberg’s printing press generated millions of copies of books. Suddenly, there were far more books than any single person could master, and no end in sight or as Barnaby Rich wrote in 1613:

“One of the diseases of this age is the multiplicity of books; they doth so overcharge the world that it is not able to digest the abundance of idle matter that is every day hatched and brought forth into the world”

Besides a Luddite position of some that rejected technological change, the invention of printing began to generate innovative new practices and methods for dealing with the accumulation of information. These included early plans for public libraries, the first universal bibliographies that tried to list all books ever written, the first advice books on how to take notes, and encyclopedic compilations larger and more broadly diffused than ever before. Detailed outlines and alphabetical indexes let readers consult books without reading them through, and the makers of large books experimented with slips of paper for cutting and pasting information from manuscripts and printed matter — a technique that, centuries later, would become essential to modern word processing.

Historically, humans have adapted to the increasing pace of information exchange with the appropriation of new practices and means to filter, categorize and prioritize information feeds.

Similarly, a couple of centuries later, the increasing presence of the telegraph multiplied the levels of stress among merchants used to more local, slower and less competitive transactions. They eventually adapted to the new pace of information exchange with new practices and means to filter, categorize and prioritize information feeds.

From social media ‘diets’ to ‘data hygiene’

What today’s most connected people share with their ancestors is the sense of excess and related discomfort, and stress linked to information load. In many ways, our behaviors for coping with overload have not changed. Besides the promises of AI and machine learning that trade control for convenience, we still need to filter, categorize and prioritize, and ultimately need human judgment and attention to guide the process.

These behaviors perspires in popular media and the many articles that share tips to follow successful social media diets, detox, or cleansing programs. The authors typically advise their readers to move away from being constantly ‘on top of things’ and to give up on concerns of missing out or being out of the loop. The diets are about replacing one behavior with another more frugal by pruning the many social networks (‘quit’, ‘uninstall’, ‘unplug’, ‘remove profile’) and contacts (‘mute’, ‘unfollow’). Yet they target a temporal improvement and fail to promote a more profound sustainable behavior with positive reinforcement.

Besides the promises of AI and machine learning that trade control for convenience, we still need to filter, categorize and prioritize, and ultimately need human judgment and attention to guide the process.

Social media platforms have also slightly updated the interfaces to support these behaviors. For instance Facebook recently started to allow users to specify the certain friends and pages that should appear at the top of the feed and Twitter introduced a ‘while you were away’ feature to its home timeline. Yet, social media feeds still feel like an endlessly accumulating pile of messy dirty laundry.

There is an opportunity to reconsider how we use social media and how we build it. Social media that gives human control to prioritize certain feeds over others, but without normalizing content into something less messy, and less complicated than a human. In fact, adapting to social media overload is not about being ‘on a diet’ than having a good ‘data hygiene’ with a set of rituals and tools. This is what I explored along with my colleagues at Near Future Laboratory with the design and development of Humans.

Introducing Humans

Humans is an app that offers a way to rationally manage too many contacts and slows down the consumption of status updates, tweets, selfies, photos of all kinds. Its design inspires from observations on how humans adapt to the feelings of information overload with its related anxieties, obsessions, stress and other mental burdens. Humans is the toothbrush for social media you pick up twice a day to help prevent these discomforts. It promotes ‘data hygiene’ that helps adjust to current pace of social exchanges.

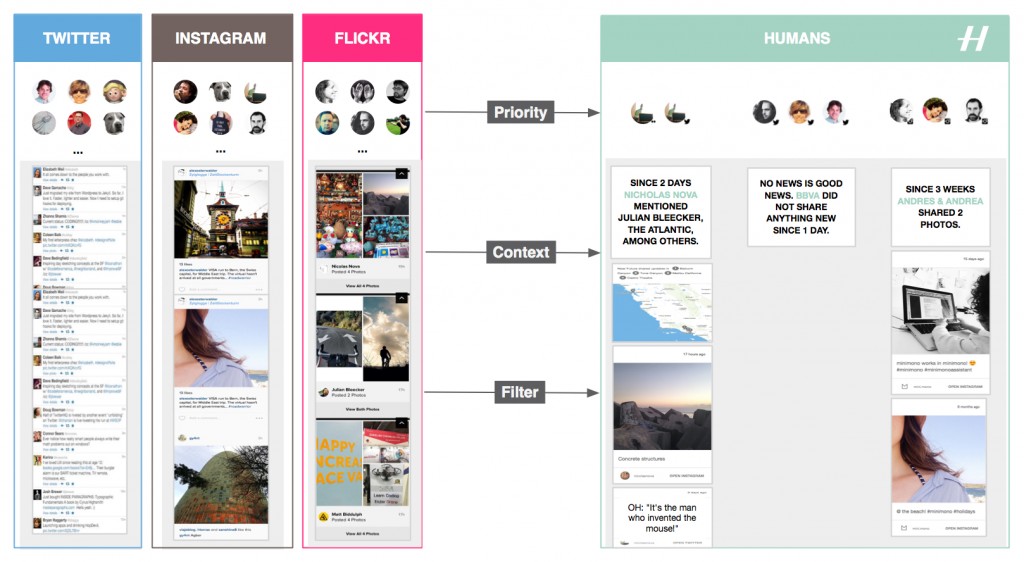

First, Humans gives means to filter, categorize and prioritize feeds spread across multiple services, like Twitter, Instagram, and Flickr. The result forms a curated mosaic of a few contacts, friends, or connections arranged in their context.

Additionally Humans strips social network interfaces and algorithms from their ‘toxic’ elements that foment addictions and arouse our desire to accumulate rather than abstract. And that without altering the fascinating dynamics of social networks. One inspiration this ‘data hygiene’ design pattern is the Facebook Demetricator provocative project that removes any number present in the Facebook interface. Its developer Benjamin Grosser advocates for the reduction of our collective obsession with metrics that plays out as an insatiable desire to make every number go higher. Another inspiration is the Little Voices app that removes the ‘noise’ from Twitter feeds and that is ‘ideal for those who like their feeds slightly quieter’.

Taken together, the benefits of using Humans are:

Reduce the compulsion to perpetually check Instagram, Twitter and Flickr

A frequent use of multiple social media services reduces our ability to contextualize and focus. With Humans, you can mitigate that online social service schizophrenia and establish a rational regimen for following without the constant barrage and noise of too many extraneous strangers’ updates. It works with the main social media platforms.

Keep away from the distractions in social media feeds

Get access to content stripped out of the social media distractions. Humans removes visual noise and arrange in their context the many status updates, links, selfies, photos of all kinds.

Mitigate feelings and symptoms of remorse whilst taking short or long offline breaks

If you have been away from your screens or too busy, Humans creates digestible doses of context that will get you up to date.

I designed and developed Humans to exemplify a new mean for ‘data hygiene’ with an interface and algorithms that adapt to human pace and do not uniquely focus on the real-time, the ‘now’, and the accumulation of ‘likes’ and ‘contacts’. Or as our fictional experts in ‘data hygiene’ would suggest:

Check lovehumans.co for more information and request the app.

The near future of data hygiene

At Near Future Laboratory, we like to investigate alternative paths for technology. As data and connectivity augment our lives, hygiene might no longer only relate to maintaining a healthy body. Connected humans produce ‘data doppelgängers’ and consume data ‘anywhere’ and ‘anytime’ at an unprecedented rate. Consequently, they start to experience discomforts such as social media overload that Humans helps mitigate.

Like other information technology revolutions, there is a necessity for people to adopt new rituals and tools. In the near future we might see emerge interfaces, experiences, algorithms, design patters that reshape our social practices and for instance:

- moderate our collective obsession with metrics and the pervasive evaluation and comparison of one self.

- reclaim space for conversation over the illusion of the connection, its ‘retweets’ and ‘likes’.

- reduce the social cost to ‘unfollow’.

- promote solitude as a good thing.

- regulate our insatiable desire to capture ‘moments’ and accumulate ‘contacts’.

- help us overcome the ineluctable situations of digital amnesia.

- empower our skills for abstraction and generalization from the ‘moments’ we capture.

- help us forget to better remember.

- invite us to expect less from technology, and more from ourselves and each other.

More on these topics in upcoming projects.

4 thoughts on “Social Media at Human Pace”

Comments are closed.