Aram Bartholl’s project “WoW” suddenly popped into my head as I was discussing the good old Mobile Social Software knee-jerk project — proximity-based friend finders. (Here is a decent video of Bartholl’s project in action.)

Proximity-based friend finders — these are the MoSoSo application/ideas in which people find people near them who share their interests, or what have you. It’s like friend searching online, or finding people with common interests, as we do directly or indirectly every so often online, only it’s done in physical space. The early canonical example is the LoveGetty device in which people key into the device certain simple parameters as to their preferences and people nearby whose devices find compatible preferences are alerted. It makes since, but truly only for a gag, or for a good cocktail party conversation. It’s simple disclosure of yourself — wearing your identity loudly in public, broadcasting it literally over the air for all to see.

We’re all used to various levels of identity disclosure online, almost always done on purpose, and deliberately. Sometimes it’s way over the top; other times its a simple, subtle representation of oneself in a modest Facebook page, or Twitter feed. Online is one thing, and the social people-practices engaged online are arguably just crawling out of the primordial goo. Aggregates of activity represent ourselves, still quite disparate and barely knit together — and it takes lots of effort to try and create a more cohesive quilt of identity, even in this age of feeds, aggregations and open APIs.

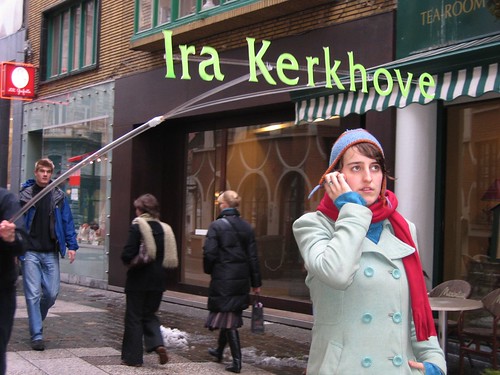

But in “real life” — in 1st life — people and their practices have had time to distill and refine the ways in which we create and represent and share who we are. in 1st life, we don’t so much disclose our identities — in the way WoW has a floating banner of our (avatar’s) name. Rather, we allow a sometimes baroque, sometimes simple process of discovery of identity.

And this is what makes Bartholl’s project so incisive and funny at the same time. How ridiculous to “broadcast” who we are in this fashion? It’s simply not consistent with the people-practices that are the norms in 1st life. And this is perhaps where Mobile Social Software can learn and understand that it’s not about the technology, no matter how simple it may seem to create linkages over networks in the real world. It’s about finding the consonant social practices that Mobile Social Software can facilitate, leading with people-principles before technology principles. That is where the design disruption lies.