<a href="http://twitter.com/bruces/status/24029892488"?@bruces pointed out this curious paper called Modifiable Futures: Science Fiction at the Bench from Colin Milburn, who sits in the Program in Science and Technology Studies that our old UCSC History of Consciousness school chumJoe Dumit heads. The paper takes a go at describing the entangled, multivalent, contentious and complex relationship between science, fact, fiction and the future. The interplay between all of these — and throw in fan cultures, society at large, politics, money, power, knowledge and authority..heck, lets just say “technoscience” and be done with the litanies — is a tricky thing to describe and always seems to make people hot under the collar lest capital-s Science feel it looses its authority as the canonical, go-to guy for where knowledge about the world comes from.

What Milburn might say — what many who appreciate the fun to be found in the rich layer cake of knowledge production — is that the interplay between fiction and fact is actually a good thing. He would say that the assumption that scientist, their ideas and their divinations in the form of science facts about the natural world is not only wrong, but it does a disservice by discounting the productive contributions that other idea-generating mechanisms can bring to the game of knowledge-production. And for Milburn, curiously — games provides a fruitful framework for his way of describing the interplay between science fact and science fiction. He uses the game “mod” — or modification — as a metaphor for the way that science fact and science fiction produce knowledge and materialize ideas.

This is an intriguing perspective for its simplicity, which is good. The simplicity should be contrasted with the oftentimes baroque offerings of explanation delivered by critical theory (and worse..philosophy) when brought to bear on the world of science, or epistemology of science. By drawing from more contemporary ideas about fan culture and then saying — hey..scientists can be science fiction fans, too, Milburn is stating what would seem obvious. (Obvious, but breeching the perimeter of scientists’ secret lair can be dangerous — cf the “Science Wars

” — and “The Science Wars” that waged in the 90’s amongst about 300 people..it got down-right nasty! Seriously..you could write a movie script from the back-biting, the misrepresentations, the gaffs and punk’ngs — the whole FBI thing interviewing historians of science at their annual conference about the where-for of the Unabomer? But..only 300 people would go see the movie..still, exciting for a clutch of Ph.D.s.)

*Anyway.

Milburn is stating that scientists should not be exempt from fandom and the larger influences of the ideas that are heavily circulated in various forms of science fiction cultures, entertainment even as they are distilled and decanted through various means that themselves may not be categorized as “science fiction.” It’s not like they ignore their imaginations, which might have caught wind of — or even been inspired by — say..Star Wars or Minority Report or Raumpatrouille Orion or Space 1999.

Milburn then goes on to say that the idea of the “mod” — the modification like the game mod, or the music mash-up, “fanfic” style grassroot storytelling that responds to the desires of fans and so on — all of these *ways of circulating and generating new music/stories/conversations should perhaps suggest that the same can happen with science when fact and fiction engage each other. Milburn describes three kinds of mods for science fiction that make it fruitfully usable by technoscience (in other words — he’s not dissing science but rather seems to be suggesting that science fact becomes better for being able to push itself beyond its own institutional limits by engaging science fiction productively): blueprint mods, supplementary mods and speculative mods.

Blueprint mods translate a specific, discrete element of science fiction and attempt to materialize it as a technical reality. The relevant example he gives is of Linden Labs using Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash as a model for their Second Life as described in the book Making Virtual Worlds: Linden Lab and Second Life

. The blueprint mod goes beyond using the science fiction as an influence or inspiration — it wants to make something that is quite specific in the text, “extrapolating and inventing a distinct technical dimension..disregarding any necessary integrity or organicity of the fiction.” Milburn mentions the seemingly endless fascination of this form of “mod” with entire book series

and Wiki pages devoted to “The Science of..” show/movie/book.

Supplementary mods attempt to approximate a science fiction concept. This means that what sounds cool but is taken to be technically impossible will be worked on to create a scientifically viable alternative. There has been work on invisibility shields that fall into this category of supplementary mods. For example, this invisibility cloak that is evocative of the cloak that P.K. Dick’s Agent Fred wears in A Scanner Darkly. I saw this device at Ars Electronica in 2008 — it is definitely an approximation but tips into this sort of supplementary mod. It seems to say — this is a very cool idea. We know it is technically intractable, but we’re going to push forward anyway with this project that begins to activate the imagination and inspire further modding.

Speculative mods is where science fiction is used in science writing and technical papers as a way of describing possible futures and the extrapolation of today into tomorrow. This is a form I find quite often — the “it’s like the ray gun in Lost In Space” sort of thing. Milburn acknowledges that that historians and cultural theorists of technoscience appreciate how science speculation, “forecasting”, futurological narratives, road mapping and so on play a role as “scripts” in the laboratory and R&D agendas. But, he says —

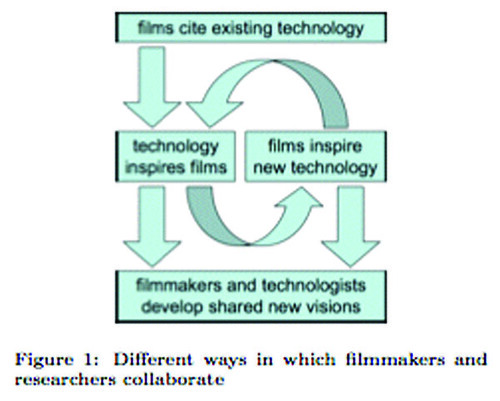

Why do I blog this? This is a great short essay that captures some of the themes of the design fiction conversations that are swirling about here and there. There’s some useful reinforcement of things that David A. Kirby has described as the “diegetic prototype” — which I think is kin to Milburn’s idea of the mod, insofar as it allows for the circulation of ideas and does not explicitly prioritize either fact or fiction.

What I find interesting is the use of the idea of the mod — a form of circulating and layering cultural forms to create something that builds upon some underlying stories and characters and worlds that are ostensibly fiction to make something material and tangible that is ostensibly fact. And then when you understand the rich ways in which ideas blur together and you stop prioritizing the fact/fiction binary — you begin to see new possibilities for imagining and creating and materializing ideas that avoids those silly cat fights over who done what first or who was the originator or an idea.

Continue reading The Future is a Mod