What do you read when reality turns itself on its head? The financial seers in the form of the genius ex-mathematics and high-energy physics Ph.D.s — the “Quants” as they’re known on The Street — failed at their assigned task of turning the many-body problem and squirrely statistics into a clear course into the up-and-to-the-right linear, inevitable accumulation of wealth future. So, now what?

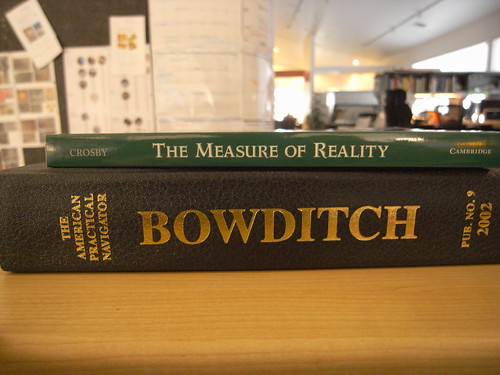

Back to basics. How has “reality” — the way the world works — been measured historically? Where did all this reliance on numbers (instead of cat entrails, tea leaves, a healthy dose of psilocybian or a good-old crystal ball) come from and why do we believe it works? For that, I’ll be turning to “The Measure of Reality: Quantification in Western Europe, 1250-1600” by Alfred W. Crosby. I was actually suggested this book during Manuel Lima’s presentation at SHiFT 2008, where he discussed Visual Complexity — the site and the motivations behind data visualization. (More about this in a future post.)

Why an historical treatment of quantification? Because I need to know more about this shift from qualitative ways of knowing the world. Quantification, perhaps more than most other ways of knowing, undergirds so much of the various assemblages and apparatuses — business, bureaucracy, technoscience, etc — that shape the worlds around us. Knowing its legacy throughout time can’t hurt, especially when thinking about small, subtle new ways of making the world.

And just to continue this general theme of “back to basics”, I thought it couldn’t hurt to have a copy of “The American Practical Navigator” by Nathaniel Bowditch tucked away in my emergency “go bag” (along with running shoes, a few power bars, keys to the rendezvous beach house south of LA, two liters of water, and a couple grand in cash.) Way finding, like reality, needs a good re-think.

If it wasn’t more gratuitous than pragmatic, I’d add Zizek’s “The Sublime Object of Ideology” so long as we’re trying to figure out why we do what we do, even if we know it’s the stupidest thing in the world.