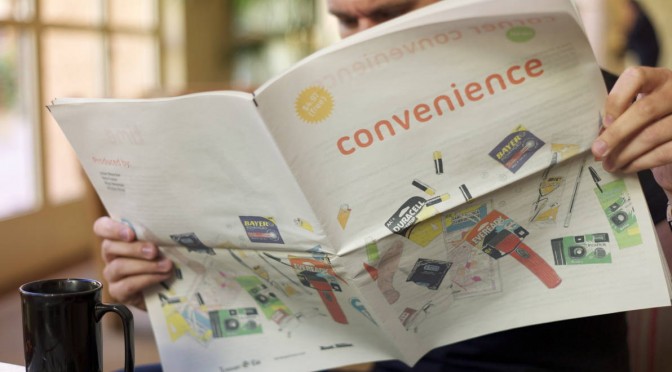

We made a newspaper through our friends at RIG‘s lovely Newspaper Club service. We — myself, Nick Foster, Nicolas Nova and Rhys Newman — collaborated on this. (Rhys did the lovely drawings, by the way.)

We printed a hundred or so. They’re real physical things of course. But you can also download a PDF of Convenience.

The newspaper is called Convenience and it’s based on the hypothesis that all great innovations and inventions find their way into the Corner Convenience store. Take for example, the nine we selected to feature in the newspaper, amongst a couple dozen:

AA Battery (Power)

BiC Cristal Pen (Writing)

Eveready LED Flashlight (Light..and laser light!)

Durex Condom (Prophylactic)

Reading Spectacles

Map (Cartography/way-finding)

BiC Lighter (Fire)

Disposable Camera (Memory)

Wristwatch (Time)

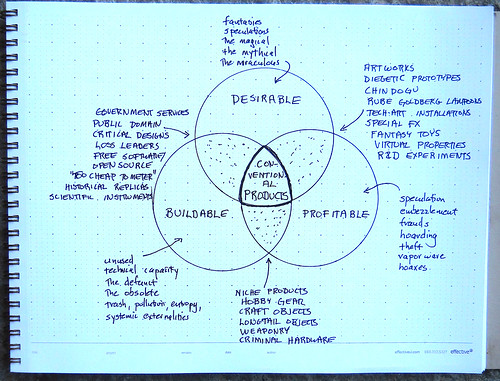

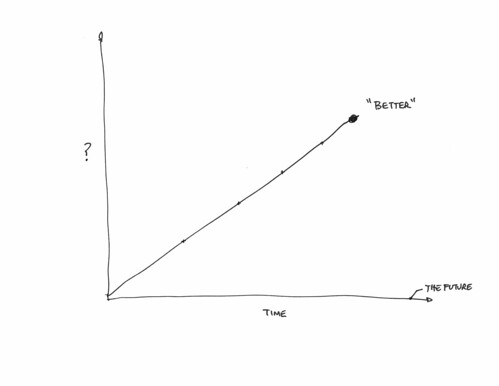

It’s a hypothesis designed to provoke consideration as to the trajectory of ideas from mind-bogglingly fascinating and world-changing when they first appear to numbingly routine and even dull by the time they commodify, optimize and efficient-ize By then, they become so mundane, quotidian and routine that the only way to enliven them is to offer sales discounts (3 for 99¢), packaging copy eye candy (New! Comes with batteries!), color variants, add a few new bells and whistles (Copper Top! Sensually Lubricated!, all done in remarkably infinite variety and a good dose of insight on human impulse and psychology by our friends downstairs in brand marketing.

In the paper, each of our nine items gets a bit of a mini dossier. Where, when, how, how long, by whom? And we have an op-ed section. The over-arching implications here are to consider that great things need not be whiz-bang, flash-bang Military robots+monkeys sorts of things. Or even sleek screen-y things. Innovation can happen in the decidedly less celebrated, less red carpeted approach of just making little things much better and settling for small, deeply impactful implications.

In the paper we also have a center piece that reminds us of the role the Corner Convenience has played in the modern cultural barometer of popular cinema. We did that center section because much of out thinking centered around the quotidian character of the Corner Convenience as represented in film. But also — @fosta and I now here at Emerge 2012 at the Arizona State University in Tempe Arizona (following along at #emerge2012asu) to conduct a Design Fiction workshop.

Our locus of interest? The Corner Convenience of the near future, of course! We are asking ourselves through filmmaking — what will be in the Corner Convenience in a four or five years time? We want to make our own little films to exhibit those things using the styles and genre conventions of Design Fiction.

Corner Convenience

This is where we are, at the counter of your local convenience store — the corner bodega, kiosk, liquor store, small grocer. We could be at the independent certainly. Increasingly we’d find ourselves at any of a number of global chain stores — 7-Eleven, Express Mart, AMPM, A-Z Mart, Get Go, Get n Go, Stop’n’Go, QuickCheck, QuikStop, Kwik Shop, One Stop, Store 24, 7/24, Ministop, R-kioski, Circle K, Kroger, Wawa, Relay, Żabka, Lawson, All Days, In & Out, Convenio, Everyday, Spar.

Just call it Corner Convenience.

Let’s ask ourselves — what makes these stores convenient? It didn’t take long to get here so we’d have to say that location for most of us would be synonymous with convenience.

Next might be the hours the Corner Convenience keeps. This measure of convenience often appears as a kind of subtitle to the store name. “Open 24 hours”, “Open Day & Night”, “Day and Night Liquors”, “We Never Close”.

They are off of every exit on any highway. Around every corner of most neighborhoods. They say they never close. It’s 1:14am. You need gasoline. Turn right.

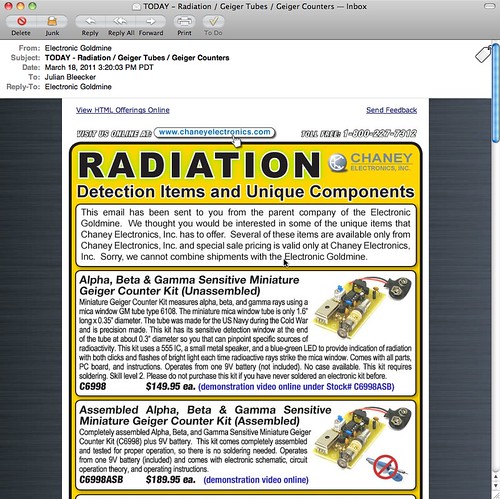

Summon the image of a weary, pimply-faced 20 year-old Guatamalean immigrant seen safely time-locked into his protected cash register cage in a small beach town in Southern California. We’re free to wander the store — a few aisles of chips, meat jerky, king size candy bars, breath fresheners, throat lozenges, bubble gum, rotissing hotdogs, magazines. Behind two epic walls of built-in refrigerators — bottles of bottled water with excruciatingly meaningless packaging variations, whole milk, low-fat milk, half-and-half, Florida orange juice, orange drink, things to drink, junky pep drinks, Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Monster, fancy Woodchuck Cider nestled by a small scrum of chilly, perspiring white wines, and then a formidable flank of a regional workmen’s after work favorites including 24oz Budweiser Clamato and its variations. Locked safe in the after hours attendant’s cage — ciggies, flavored cigarellos, Zig-Zag papers, condoms, herbal supplement packets for endurance and fortitude, lighters, batteries, laser pointers, analgesics three varieties of aspirin, and some flavorful cough suppressants.

The attendant-cashier idly scrolls through text messages — or electronic mail, or news from home, or considers a death-blow of a move in the Words with Friends game he’s playing with a cousin in Arizona, or updates his Facebook profile photo, or Tweets that he’s bored to 740 followers..it’s hard to tell from behind the 3/4 inch bullet proof. And I don’t really care if he’s amazingly sending digitally encoded radio transmissions to outer space and back because I’ve just bought $53 of Saudi gold. It came over the Atlantic and through the Panama canal in an oil tanker just for me.

The Corner Convenience is a vault containing the treasures of great, world-changing innovations throughout all histories. Truly. We should see our Corner Convenience as a living Neighborhood Museum of Innovation. Someone should enshrine these and teach the lesson to every secondary school student. Think of the product tie-ins. There could be an international holiday commemorating the deep-seated history of innovation in your local 7-Eleven. Where are the brand marketing people? They’ve dropped the ball on this one.

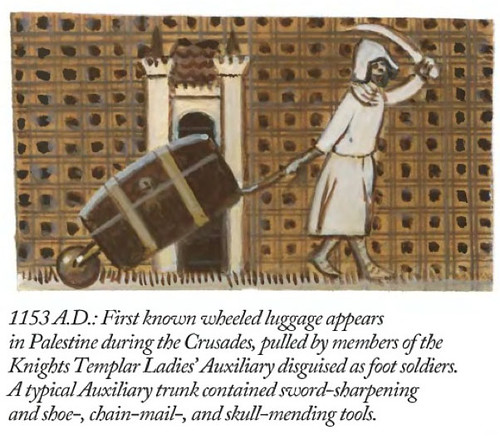

We have at our finger tips the things no one would have taken for granted 50, 100, 200, 500, 10000, 500,000 years ago. There it all is. Fire, for chrissake — and disposable? In any color one would like, or with your favorite sports team printed on it? Are you kidding me? Flick and fire. Flick and fire.

Have an achy head? No leaches at hand? Don’t feel like chewing on the bark of a Slippery Elm? Well — have some acetylsalicylic suspended in a dissolving capsule that you swallow. Nothing to swallow it with? Have some fresh, filtered water, brought to you by truck and ship and conveniently packaged in a dubious plastic bottle. Feeling randy, but not ready to start a family? Pick your variety, shape, size, texture, degree-of-package-salaciousness condom. Concerned about performance? Have a grab-bag of herbal fortitude. Need to make a phone call to *anywhere? Get a disposable cell phone, talk for 120 minutes then throw it out.

It’s all right there. Selection, variety, color — sure, we expect that. But do we stop to marvel at the epic travels in space, time, refinement, iteration, industrialization these mundane, ordinary conveniences have made?

Convenience is the name of the awards ceremony at which capitalism admires itself. Convenience is the final measure of mass production’s success. It is the asymptotic long-tail of industrialization, a tail whose zero is 99¢, 3 for 1, buy-one-get-one-free. Industrialization is found in the rash-dash coupon books that litter our recycling bins. It is the baroque, oddly seductive sales circulars encouraging us to tramp down to our local shop and get a dozen eggs, a flank of beefsteak or a case of birdshot. We find industrialization tucked into the ad supplements of old-fashioned newspapers — the paper newspapers — reminding us that we might need a ream of sustainably farm-harvested non-toxic bleached white paper for our $99 laser light powered printing press.

How do we applaud convenience? Does it represent success insofar as much of the world — though certainly not all — soaks in it? Is Henry Ford, godfather of industrialization, doing an exuberant, boastful Running Man in his mausoleum? “I done done it! I done done it! I done toldya! I done toldya! You know you waaaant it! You know you waaaant it!”

If it is success, it is a conflicted one. No proper post-disciplinary, post-modern Industrial Designer truly *wants their work to end up in the Corner Convenience. That is unless they have fully embraced this sparkly, polished Muzak-filled museum of over-produced, barely distinguished things. They must make peace with the fine folks in brand marketing, the high priests of endless variation and spell-casters of seduction. (We shouldn’t dismiss the Industrial Designer’s dream for another sort of Corner Convenience, albeit of a different register. The convenience store that embraces the mass industrialized infamy of the considered and crafted — Design Within Reach.)

What we have produced for your consideration is a kind of program guide to the counter of your Corner Convenience. A simple, small reminder of the travels that all great things make in this era of mass-convenience and massive, world-scale industrialization. It is with irony that we have made this by re-purposing the newspaper printing press. We are now able to quite conveniently make such a thing — a newspaper, for chrissake — through the foresight and disciplined hard work of the people, presses and algorithms of Newspaper Club. These algorithms marshal unused resources and put them to work in a way that lets the four of us make and print 100 newspapers cheap as chips.

Do not confuse convenience with that which is owed you. Do not act entitled to convenience. Revel in it. Designers, refine it and have the humility to acknowledge what it is, truly. For now, picture the 40-something, father to a few and set to task to create with his colleagues a newspaper on the topic of Convenience. Thus he goes to his Corner Convenience, armed with a 4×6 index card’s list of 10 things of convenience to buy as props so as to consider these conveniences in their physical form. He’s a familiar and regular, yet anonymous patron to his local Corner Convenience. This time though, rather than a quart of late-night milk he runs through a list on an index card: “I’ll take those eye glasses, the 3-pack of colorful BiC lighters, a map, um..condom — no, that one there, in the purple packet..no just one’ll be fine — flashlight, BiC cristal pen..and a watch.” One would rightly think he has slipped his moorings to become the neighborhood apocolyptic, prepping for the trending #2012 topic that foresees The End to it all. And of what would that end be? What would we have no more? For some it would be life — for surely there will be the floods and famines and fires. Mostly though, it’d be an end to Convenience.