Making our own stuff — what does it mean, how do you do it? There is a sense that the ability to make our own electronic/digital/computational “stuff” is not just fun, but has some larger purpose that’s related to impulses of DIY sensibilities. Making your own devices has a implicit cultural and political message. That is, we can be “productive consumers” as Ruth described yesterday. We can produce the things we need or enjoy or desire based on our own principles, ethics, senses of fun and so forth. This I think is very good, and very important.

Left To Our Own Devices (on SlideShare)

What does this phrase mean, “left to one’s own devices”?

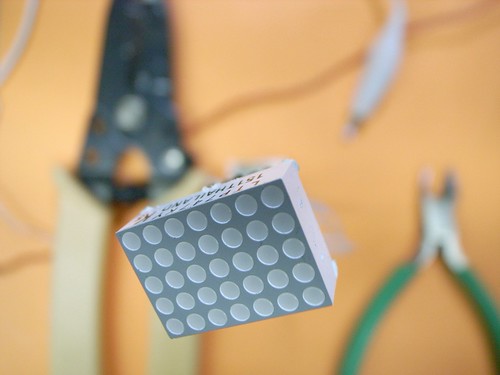

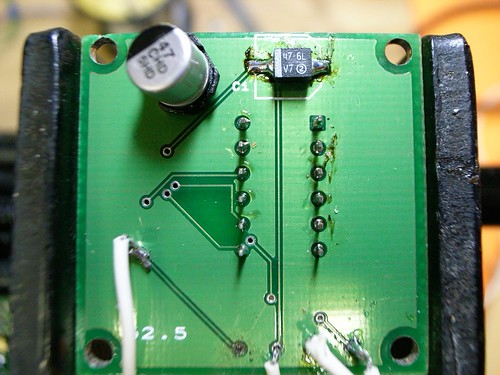

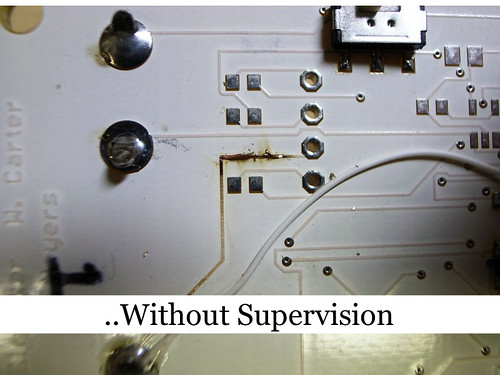

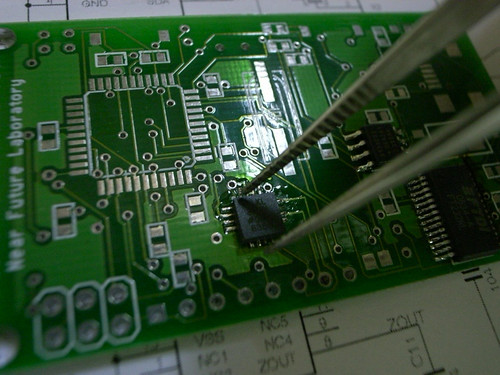

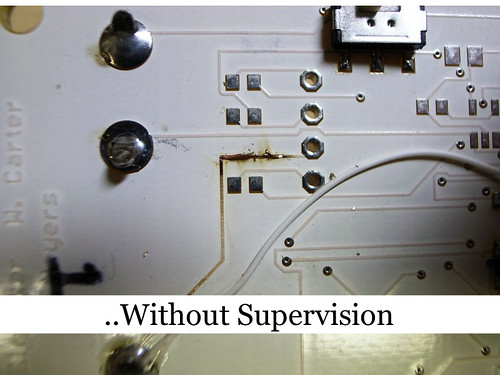

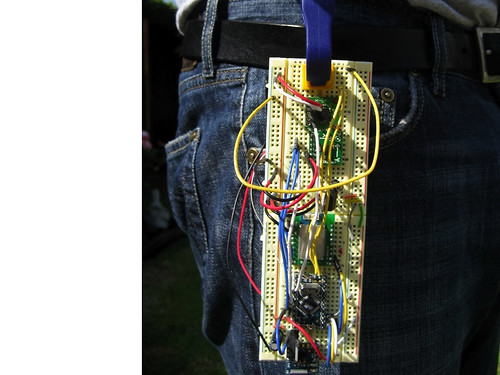

The opportunity to make mistakes and learn from them is crucial to making your own stuff, and developing the skills to think for oneself. This is a mistake I made recently that burned out part of a board. While it was a setback, it was only temporary and in the process, on my own, I learned.

Making mistakes or probing the boundaries of what works and what doesn’t is a powerful way to learn, and, mostly, gain confidence and mastery. So “left to our own devices” also has this sense of learning, or understanding about things that were previously a kind of black art.

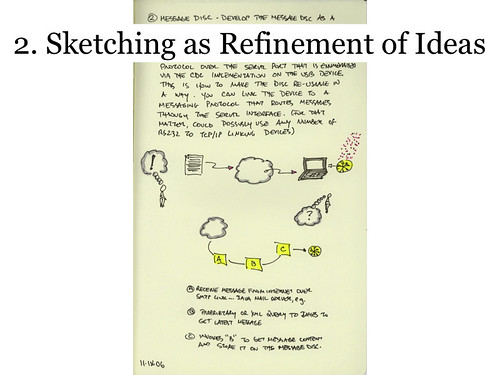

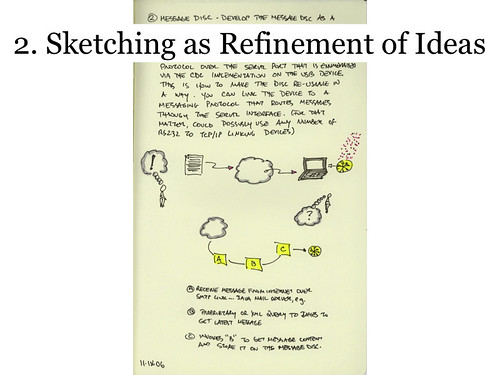

And so what does this mean for “sketching in hardware”? I want to suggest three things, or observations that I think describe what “sketching in hardware” is about. Starting at the highest level is “sketching as critique.” I think there’s a kind of creative or cultural criticism that goes on when sketching hardware.

The “Wouldn’t It Be Cool If..” approach to making things. This is design that is driven by the imagination. I notice many projects that suggest this motivation — for instance, it would be cool to have a mobile phone that has no features except to make telephone calls. In fact, it might not even have a display, like an old analog phone. Why do we do this? Part of it is to demonstrate hardware sketching acumen and skills. But I think there’s also an implicit criticism about the way things are that suggests a response. Making things different than they are.

The “What Would The World Be Like If..?” approach to sketching is kind of like writing science fiction by making things that ask what would the world be like if.. These are things that are not necessarily “rational” in the way we often think about rationality. But they are meant to provoke questions about certain aspects of life in the same way that the best of science fiction does. It forces us to consider ourselves and our ways of living by helping us find a partial perspective that is outside of our routine, quotidian lives.

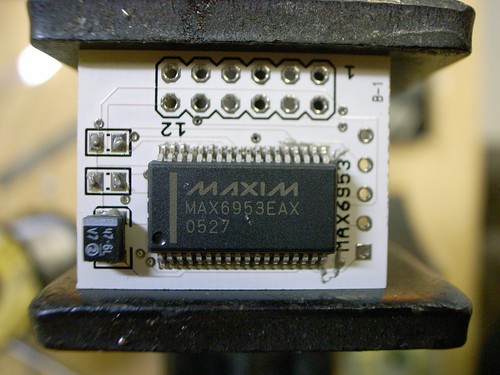

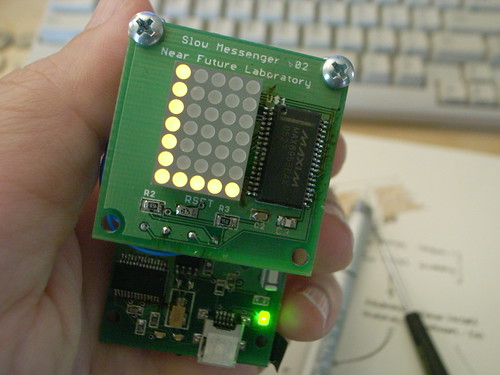

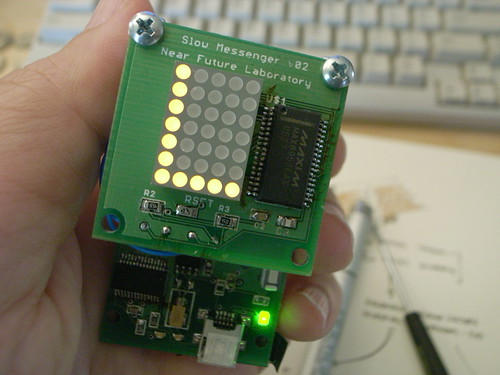

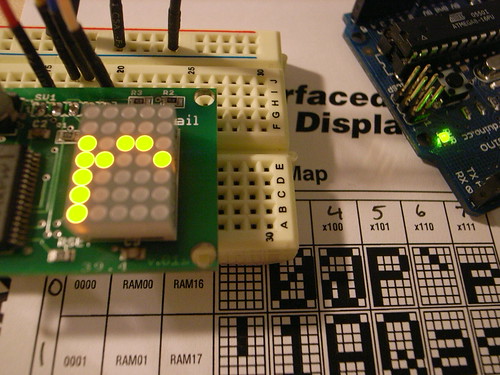

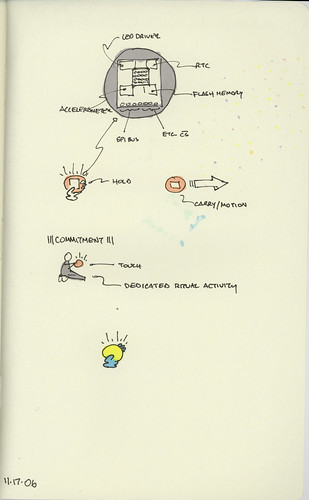

This is the World’s Slowest Instant Messenger, or “Slow Messenger” for short. You can send an instant message to it over, for instance AOL IM, and the message from your buddy will reveal itself over many hours or even days, one character at a time.

Why do this? To imagine what such a world might be like if we communicated slower than we do today. The reason for doing this is more as a thought experiment imagining a different kind of world — either a science fiction world where things are a little different, for instance a world in which slowly unfolding messages are considered a polite, perhaps regal form of exchange, rather than the terse, abrupt, disruptive “fast” mode of communication. It’s also evocative of letter writing traditions, where much time was spent carefully composing a letter that communicated much more than the short message styles of digital exchange. It’s a sci-fi device. But, it needs more than just a story about it — you need to create the device and live with it and share it with people and friends to learn more about the concept.

“Sketching” implies of course making meaning through inscriptions — drawing or writing ideas, as in sketching the outlines of a thought that might be developed further, beyond the inscription. For instance, it might become something slightly more durable and enduring — into something that you can create and share with others. Refinement.

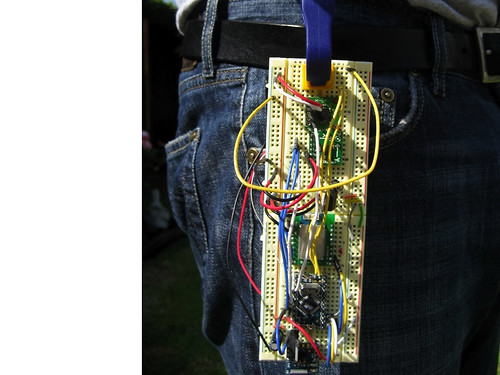

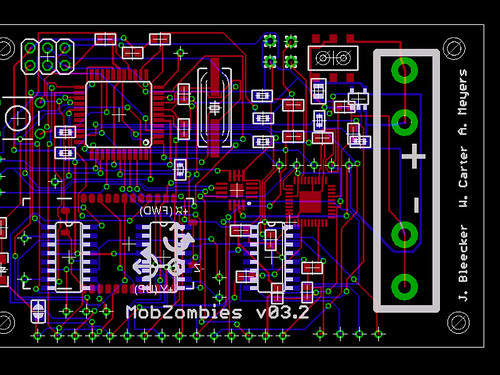

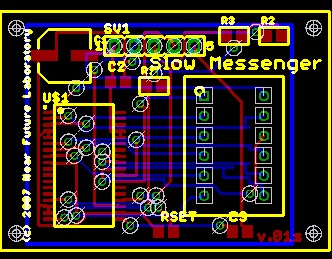

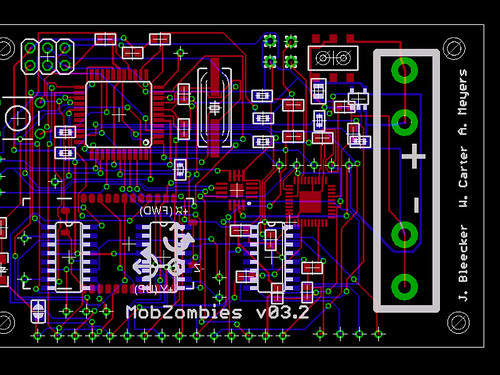

You can easily go from a prototype that’s a bit messy and experimental..Refine that through a more formalized design that starts to close the gap between prototype and an “end product” whatever that might be.

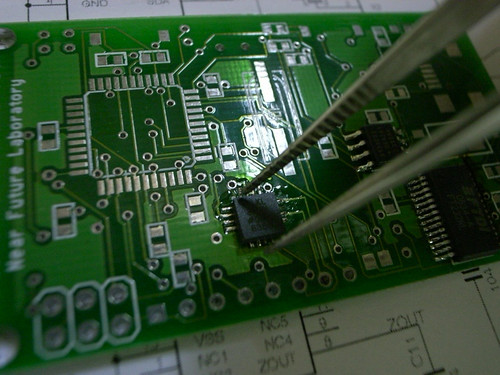

And doing the construction oneself is important — part of the trade craft is a familiarity with the process.

Being done, and refining is a rewarding part of the process of making your own devices.

Creating our own culture of devices is one way of finally ending the myth that there are things called “end products” — it indicates that everything that consumers may consume are always in flux in many terms. I don’t know much about product design, but I do know that designs evolve continuously particularly in the hands of those who are in the cycle of evolving them.

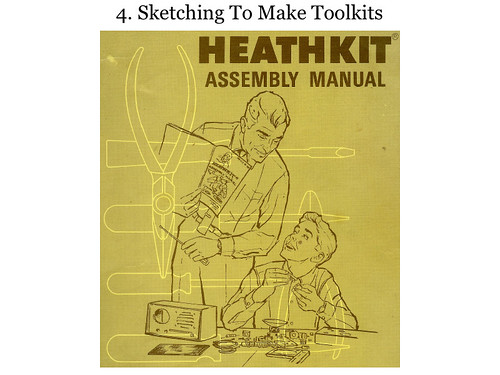

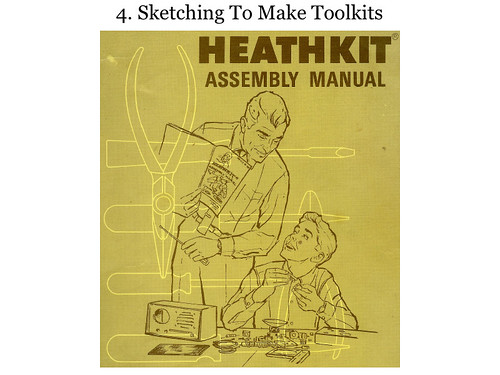

What about toolkits?

1. Need to be crafted carefully so that you don’t have a glut of things that all look a like — the China Syndrome of knock-offs and copied ideas. This is a bad thing except insofar as it teaches fundamentals. When tool-kits become ways to make the same thing over and over again, creativity wanes.

2. Toolkits are not software APIs only. Sparkfun is a toolkit because it provides the resources to learn, not just an interface for connecting to some sort of sensor.Tom Igoe’s a toolkit. Arduino.cc is a toolkit. I believe that “Sketching” as we’re talking about it here is a craft, and crafts take time and discipline to master and it can be hard. But that mastery is important to moving toward a position of creative abilities. Tools should not substitute for community engagement. Rather than just using “turnkey” tools at some point you want to participate with the ultimate toolkit — the community.

Thanks.