Just some short notes for myself on this book NONOBJECT by Branko Lukic with words by Barry Katz and a foreword by Bill Moggridge. I’ve been eagerly awaiting the arrival of Nonobject, a book that reveals quite a number of speculative objects — that are described as experience-centric design research that push the boundaries of possibility. The objects themselves do innovation through design beyond physical boundaries. As the New York Times describes it — the objects are about freeing form from function.

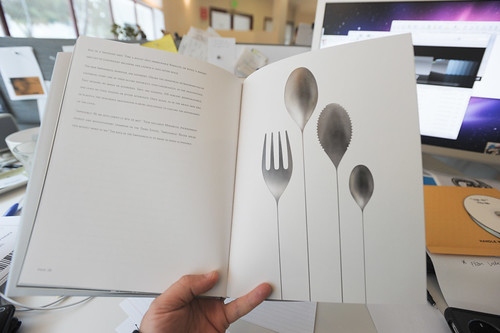

What I appreciate about the objects are the way they take a theme and then stretch it to extremes along a particular experience axis. For example, this set of flatware that has these very long impossibly thin handles to them — made of the impossible, whimsical material “Thinium.”

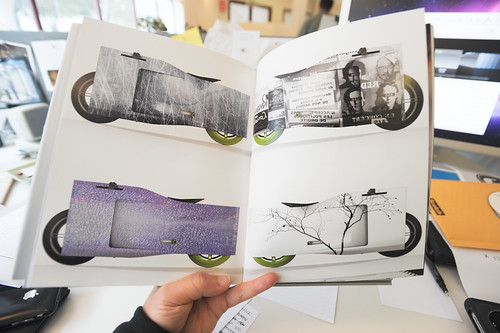

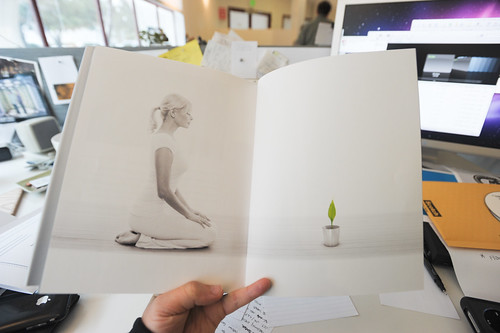

The book is chockfull of luscious renderings, gooey wordy designer-y descriptions of beautiful CAD models. There are beautiful human models serenely poised over expertly rendered CAD objects. The pages are thick and smooth, like pulled sugar-y ribbon candy. You want to lick the pages and their CAD models to see if they will have an impossibly rich, whimsical taste as well.

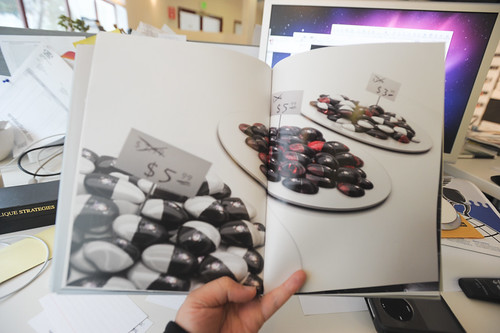

There are some curious things in here that tip into the realm of design fiction where the design actually brings me to the point of confusion, where I am unwittingly compelled to suspend my disbelief such as when one sees something and wonders if it isn’t actually real, already on Engadget. These are things that are just on the cusp of believability because they are consistent with the ways that ideas and their materialization evolve. Like — you could believe that a couple of future-forward thinking venture capitalists pooled $5 million to finance the design, tooling and short-tun manufacture of some especially curious bit of digital product concept work.

Most of the things in Nonobject deflect away from design fiction — at least the sort that closes the gap between idea and its possibility. They are truly more like speculative knowledge objects. Things to ponder over and go — hmmmm..curious. Nonobjects don’t make you want to do a google search to find out when the thing is going to be released, or search the leaked items on Gizmodo or something, or place a pre-order. For the Laboratory’s Bureau of Design Provocations, this sort of diegetic prototype is much closer to being there, in the world — than a gooey CAD render could ever be. Evolved visual literacy in this day and age does not CAD renders as much more than what is created by the designer, sitting with their modeling software, satisfying their primal designers’ urges to dream about a world in which everything looks like it should be moving very fast, or have organic, hand-made pebble-like forms, &c.

Some of the nonobjects tip into the realm of plausible. The “Behind the Scenes” camera tips into that sort of thing. A camera that captures what’s in front of the lens in a traditionally way — but also what’s behind. This is intriguing design fiction in that it seems quite possible, despite not existing. And it gets one thinking about the experience for people in the world, not just the form and un-functionality of a spectacular dinette set. But — even this makes one stop for a moment. Wouldn’t there be lots of photos of half of the photographer’s head? As soon as you start down that path, you *sigh and slump..just a concept.

Now, I’m not saying that concept-ing and vision-ing and all that does not serve a useful purpose in advancing design. It raises questions and provides material to ponder priorities and principles. It points to unusual things that help those less versed in the possibilities of design to see more broadly as to what the capabilities of this craft might be. It allows free exploration without material constraints. It’s far-fiction, unabashed dreaming and pondering. It distances itself from the material world, the world of tangible needs, constraints and exists almost exclusively in the imagination.

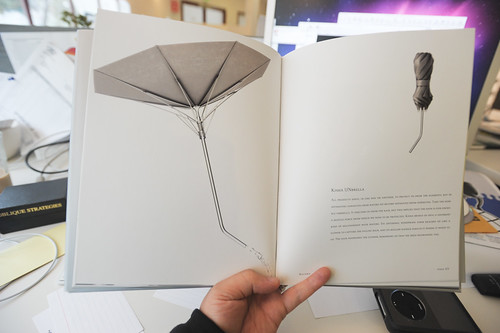

At some point this sort of concept-ing and vision-ing tips into the obscure poetry of design that is for designers themselves and really misses the opportunity to translate ideas into the material of the world in which humans live and die. Umbrellas have potential and possibility for being better and different, of course. I have to say though — this particular near future umbrella just confuses the bejezus outta me. This would be curious and even a good design-joke if it said less about watering a lone flower than the rhythms of cheap $5 umbrellas that you get on the corner that end up failing and turning inside out. I mean — a design fiction umbrella that could turn inside out if a torrent of wind decided to do so and *still remained functional as an umbrella..now, that’d be something much more legible and perhaps even tip into the category of “wheels-on-luggage” — like..someday we’d say to ourselves: “what took Totes so long to make the wind-accomodator umbrella?” If Totes cooked the Nonobject “Kisha” I’d get very French and *pffft with a *shrug.

This is sort of where I lost a bit of enthusiasm. While I like the direction and motivation here, this did not feel like the sort of design fiction that I lust after. It seemed very designer-ywith a heavy emphasis on the perfect render. Good design fiction in my mind tends more towards believable, pushing towards the suspension of disbelief as a core tenent — because then you enter into that middle space of confusion tending towards possibility, rather than the dead-giveawy of an expert CAD render in Keyshot or Hypershot or Rhino or whatever.

Now, this is a bias. I’m a design fiction guy, a design fiction-y designer. I believe that a design that tells stories about how the world could be, or what it may come to be is one that serves a purpose in a deep, ideological way to make things better. And, in the two or so years that we here have been exploring and producing design fictions we’ve found that they should be props that live in the corners so that the attention they draw to themselves in only a secondary or tertiary fashion. Fetishize them too much and the magic falls apart. Ancillary things aren’t highly rendered on white backgrounds. So — maybe nonobjects are just something entirely different. They aren’t convincing they way I think a good bit of near future science fiction can become a motivator to create (or avoid) the world it describes. In an important way, design fiction is more than fantasy renderings of impossible worlds and their contents. Design fiction is motivated to bring about change; to make things a bit better. Speculating and fantasizing is fine — an important function. But it leaves one wanting for a set of more tangible objectives, goals, principles or scripts to getting from here to a “there” that’s better than what we have now. It motivated by a loose philosophy that underscores the fact that real, material, hand work *can bring about change. When I see CAD renders, that’s only a small step towards that because our visual culture has adopted and become quite sophisticated — when something is rendered, we can tell. And that erodes the important illusion of possibility, the illusion that closes the gap and makes one wonder if this thing is real, or is this story I’m being told journalism? Or fiction?

These are perfectly captured, fantasy objects. For me, they look too fast, too impossible, too much like the Industrial Designer’s dreams rather than props reflecting the complexity of a fraught, much-less than perfect world. It’s singular — one person in charge of everything, which may indeed be the Industrial Design fantasy par excellence.

Continue reading Nonobject Short Notes