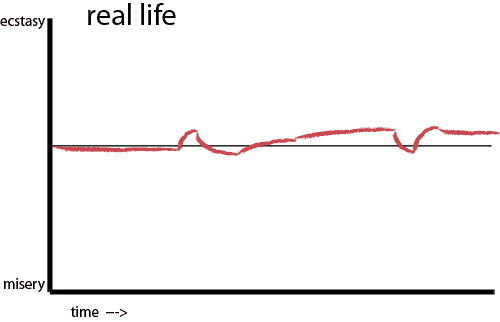

A sketch in 2D of real life as David Sivers reflects on remarks and a drawing done at a talk by Kurt Vonnegut where he is explaining his perspective on why people like drama. The conclusion, summarily: life is boring and without change. Drama brings that rollercoaster ride into our experience. And, if I remember my high school biology correctly, the human sensory apparatus responds to change more so than steady state. Which may be the biometric quantification of boredom. You know..”quantified-self” in its most fundamental, meaningful sense. Whoever’s graph does not normalize out to “boredom”, wins.

So the question here that is intriguing circles around this question of communicating ideas, socializing ideas by pumping them into the circulatory system of human meaning-making, human ear-listening, creating knowledge and insight from ideas and then inciting the will in such a way as to bring about material change in the world. A “boredom” graph won’t do this. There is no change, no inflection into other experiences and other possible near future worlds. What sort of change and inflections might one (or me, I suppose) strive for? The kind of change that creates more habitable ways of living. This is the change that matters, and why design is, from my mind, so important in shaping the world into a richer, more meaningful, less boring place. Objects, let’s say for the moment, that can create these dramatic stories around themselves. Certainly not by themselves, but like the MacGuffin, something that takes you on a pursuit, or makes something meaningful and ultimately rewards you in a way that makes life more worthwhile to live.

This is called bios [bible] by robotlab (Matthias Gommel, Martina Haitz and Jan Zappe). A machine in the ritual action of inscribing perhaps the world’s most widespread dramatic stories — the Bible. This machine will inscribe, as a scribe, in this style of drawing letters, the full text. It will take seven months. The plain motivation by the artists comes down to this: “The installation emphasizes scripture as the elementary function for religion and science — two cultural systems that are fundamental for societies today.”

A bit bland, and arguable, of course, but this only comes from the “wall text” found in the exhibition documentation, which always limits the discussion out of production constraints. That’s fine.

Whatever it says in this brief remark, being the sort to invest more attention in systems of meaning-making and knowledge circulation, to me it is less the script — the ritualize handwriting — than about stories that activate the imagination and thereby the will to make material change in the world.

Why do I blog this? Story telling is not only intriguing to us here at The Near Future Laboratory, it is a crucial socialization ritual. A friend remarked recently that we tell stories to remind us of who we are, or, variously, to refashion our own image of who we are — even if they are the same little silly “small talk” chatter about some experience. Okay, this may not be the insight of the year or anything like that, but it helps with the comprehension of various things — like, why an idea or object or something needs to exist in time, over time if it is to become comprehensible. Even if we see some weird designed fiction object that has no previous relationship — it’s foreign in a way — a story must be told about it that brings it into the quotidian, “boring” everyday. This is why I am intrigued by this sort of design fiction style of representation where the thing that would normally be exciting — a new gizmo, or something that indicates an evolution of today’s interaction rituals into a near future — that thing is made ordinary, or even burned-out and chipped and broken in places. So the fantastic exciting dramatic thing of today, has moved into a near future and become either ordinary, or underwhelming in a way. It reflects the graph of promises of great new things, and great new ways of interacting, or making toast — whatever — and then just fulfills the inevitable conclusion of — “ho, hum” present tense worlds, with your klunky, problem-prone, Ono-Sendei Industries Super Deluxe Near-Time Traveling dongle (the one you got from the Sky Mall catalog) asking you to update its firmware..again..and then shutting down, leaving you stranded and making you late for your meeting three days ago.