The business of dishonest automation and how the engineers, data scientists and designers behind it can fix it

“The pilots fought continuously until the end of the flight“, said Capt. Nurcahyo Utomo, the head of the investigation of Lion Air Flight 610 that crashed on October 29, 2018, killing the 189 people aboard. The analysis of the black boxes had revealed that the Boeing 737’s nose was repeatedly forced down, apparently by an automatic system receiving incorrect sensor readings. During 10 minutes preceding the tragedy, the pilots tried 24 times to manually pull up the nose of the plane. They struggled against a malfunctioning anti-stall system that they did not know how to disengage for that specific version of the plane.

That type of dramatic scene of humans struggling with a stubborn automated system belongs to pop culture. In the famous scene of the 1968 science-fiction film “2001: A Space Odyssey”, the astronaut Dave asks HAL (Heuristically programmed ALgorithmic computer) to open a pod bay door on the spacecraft, to which HAL responds repeatedly, “I’m sorry, Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that“.

1. The commodification of automation

Thankfully, the contemporary applications of digital automation are partial and do not take the shape of an “artificial general intelligence” like HAL. However, the computational tasks that once were exclusively applied to automate human jobs in critical environments like a cockpit have reached people’s everyday lives (e.g. automated way-finding, smart thermostat) and the techniques often deployed for more frivolous but yet very lucrative objectives (e.g. targeted advertisements, prioritizing the next video to watch on YouTube).

“What concerns me is that many engineers, data scientists, designers and decision-makers bring digital frictions into people’s everyday life because they do not employ approaches to foresee the limits and implications of their work”

The automated systems that once relied on programmed instructions based on their author’s understanding of the world now also model their behavior from the patterns found in datasets of sensors and human activities. As the application of these Machine Learning techniques becomes widespread, digital automation is becoming a commodity with systems that perform at Internet scale one task with no deep understanding of human context. These systems are trained to complete that “one” job, but there are evidences that their behavior, like HAL or a Boeing 737 anti-stall system, can turn against their user’s intentions when things do not go as expected.

2. The clumsy edges

Recent visual ethnographies at Near Future Laboratory like #TUXSAX and Curious Rituals uncovered some implications of that commodification of automation. In a completely different scale of dramatic consequences that brought down Lion Air Flight 610, these observations highlight how some digital solutions leave people with a feeling of being “locked in” with no “escape” key to disengage from a stubborn behavior. A wide majority of these digital frictions provoke harmless micro-frustrations in people’s everyday lives. They manifest themselves through poorly calibrated systems and a design that disregards edge cases. For instance, it is common to experience a voice assistant unable to understand a certain accent or pronunciation or a navigation system that misleads a driver due to location inaccuracies, obsolete road data or incorrect traffic information.

These clumsy automations can be mitigated but will not disappear because it became impossible to design contingency plans for all unexpected limitations or consequences. However, other types of stubborn autonomous behaviours are intentionally designed as the core of business models that trades human control for convenience.

3. The business of dishonest automation

Many techniques to automate everyday tasks allow organizations to reduce costs and increase revenues. Some members of the tech industry employ these new technological capabilities to lock customers or workers into behaviors for which they have no legitimate need or desire. Those systems are typically designed to resist from their user’s demands AND are hard to disengage. Let me give you a couple of examples of what I call “dishonest automations”:

3.1. Data obesity

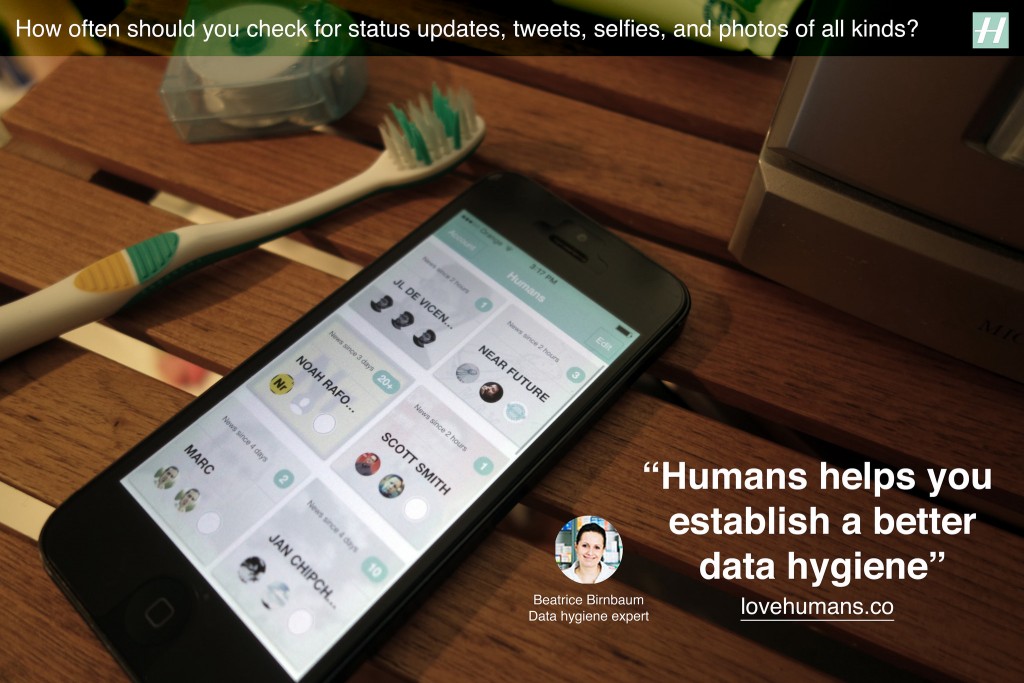

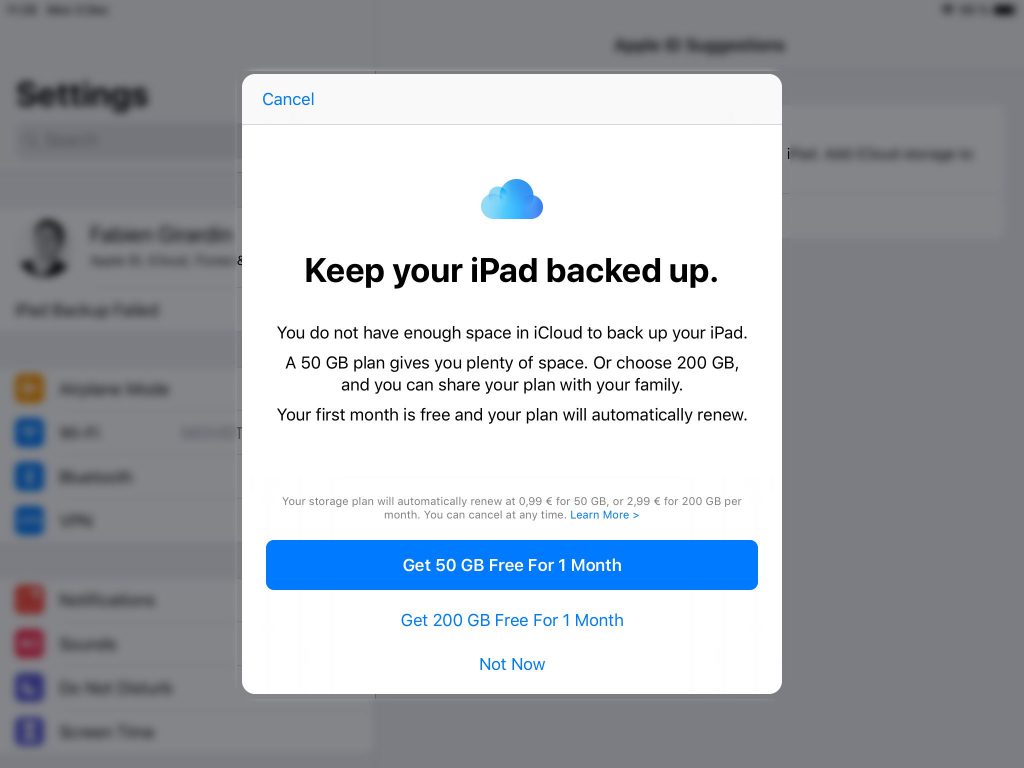

Automatic cloud backup systems have become a default feature of operating systems. They externalize the storage of personal photos, emails, contacts and other bits of digital life. Their business model encourages customers to endlessly accumulate more content without a clear alternative that promotes a proper hygiene with their data (i.e. nobody has yet come up with “Marie Kondo for Dropbox ™”). Regardless of the promises of the providers, it becomes harder for people to declutter their digital lives from a cloud storage service.

3.2. Systemic obsolescence

Today’s apps automatic updates often increase the demand of resources and processing power for cosmetic improvements almost in a deliberate attempt to make a hardware obsolete and the software harder to operate. After years of impunity, there is now a bigger conscience against systemic obsolescence because it is wasteful and exploits customers.

3.3. Digital attention

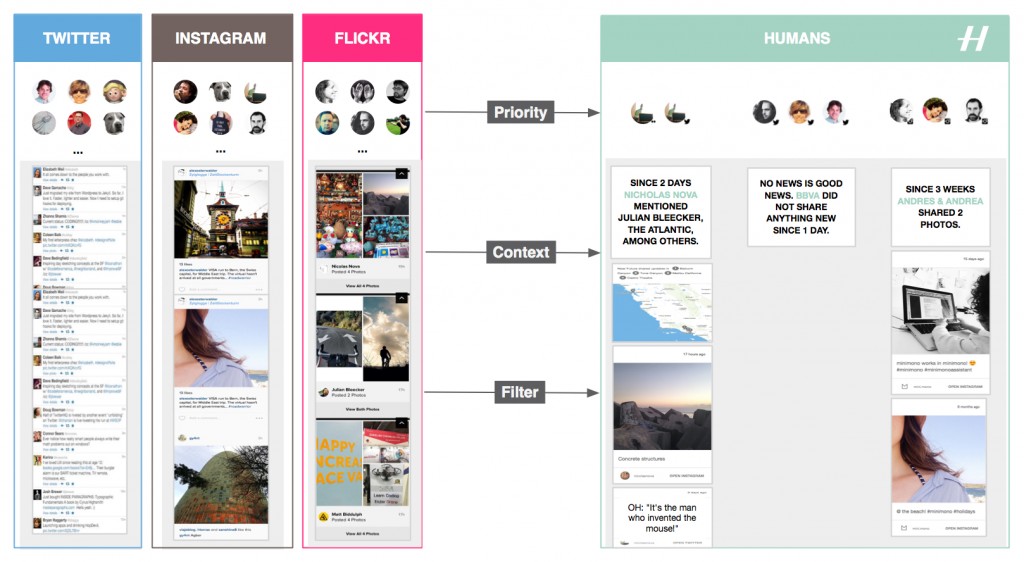

As content grows exponentially on the Internet, (social) media companies rely increasingly on automation to filter and direct information to each one of their users. For instance, YouTube automates billions of videos to play next for 1.5 billion users. These algorithms aim at promoting content for higher engagement and tend to guide people against their interest.

In the light of these examples of clumsy and dishonest automation, what concerns me is that many engineers, data scientists, designers and decision-makers bring these frictions into people’s everyday life because they do not employ approaches to foresee the limits and implications of their work. Apart from the engineering of efficient solutions, automation requires professionals to think about the foundations and consequences of their practice that transcend any Key Performance Indicator of their organization.

4. The design for humane automation

The design of automation is not about removing the presence of humans. It is about the design of humane, respectful and trustful systems that automate some aspects of human activities. When working with data scientists, designers and engineers in that domain, we envision systems beyond the scope of the “user” and the “task” to automate. I encourage teams to a) learn from the past b) critique the present and c) debate the future. Let me explain:

4.1. Learn from the past

When it comes to automation, the acquisition of knowledge in academia and in the industry are not separate pursuits. Over the last 50 years, there has been an extensive body of work produced in research institutions on the implications of automating manual tasks and decision-making. The key findings have helped save money in critical environments and prevent numerous deadly errors (e.g. in cockpits).

Today, that knowledge is not translated into everyday tasks. For instance, many engineers or data scientists do not master concepts like automation bias (i.e. the propensity for humans to favor suggestions from automated decision-making systems) or automation complacency (i.e. decreased human attention to monitor automated results) theorized by research communities in Science and Technology Studies or Human-Computer Interaction. Sadly, only a few organizations promote platforms that gather academics, artists, engineers, data scientists and designers. Industries in the process of digitization would greatly profit from this type cross-pollination of professionals who learn from considerations that already emerged outside of their discipline.

4.2. Critique the present

I believe that the professionals involved in the business of automating human activities should be persistent critical reviewers of the solutions deployed by their peers. They should become stalkers of how people deal today with the clumsy, the dishonest, the annoying, the absurd and any other awkward emerges of digital technologies in their modern lives.

When properly documented, these observations offer a complementary form of inspiration to the multitude of “naive optimism” and glamorous utopian visions of the tech industry. They provide material for professionals to question arguably biased goals of automation. Moreover, they set the stage to define attainable objectives in their organization (e.g. what does smart/intelligent mean?, how to measure efficiency?, what must become legible?).

4.3. Debate the future

In today’s Internet, the design of even the most simple application or connected object has become a complex endeavour. They are built on balkanized Operating Systems, stacks of numerous protocols, versions, frameworks, and other packages of reusable code. The mitigation of digital frictions goes beyond the scope of a “Quality Assurance” team that guarantees the sanity of an application. They are also about documenting implications on the context the technologies live, unintended consequences and ‘what if’ scenarios.

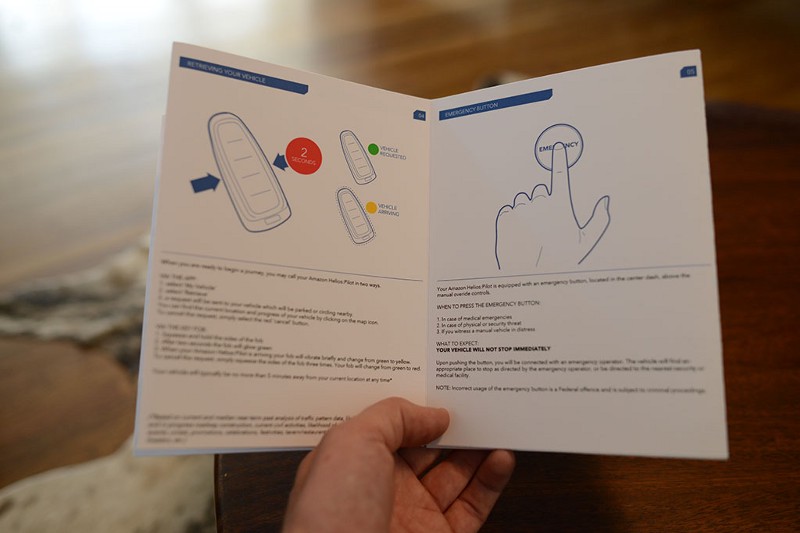

Typically, Design Fiction is an approach to spark a conversation and anticipate the larger questions regarding the automation of human activities. For instance, we produced Quick Start Guide of Amazon Helios: Pilot, a fictional autonomous vehicle. In that project, we identified the key systems that implicate the human aspects of a self-driving car and we brought to life such experiences in a very tangible, compelling fashion for designers, engineers, and anyone else involved in the development of automated systems. Through its collective production, the Quick Start Guide became a totem through which anybody could discuss the consequences, raise design considerations and shape decision-making.

5. The business of trust

Like many technological evolution, the automation of everyday life does not come without the frictions of trading control for convenience. However, the consequences are bigger than mitigating edge cases. They reflect human, organization or society choices. The choice of deploying systems that mislead about their intentions in conflict with people and society’s interests.

In his seminal work on Ubiquitous Computing in the 90s, Mark Weiser strongly influenced the current “third wave” in computing, when technology recedes into the background of people’s lives. Many professionals in the tech industry (including me) embraced his description of Calm technology that “informs but doesn’t demand our focus or attention.” However, what Weiser and many others (including me) did not anticipate is an industry of dishonest automation or solutions that turn against their user’s intentions when things do not go as planned. Nor did we truly anticipate the scale in which automation can bite back the organizations that deploy them with backslashes from their customers, society as well as policymakers.

These implications suggest an alternative paradigm that transcend the purely technological and commercial for any organization involved in the business of digital automation. For instance, a paradigm that promotes respectful (over efficient), legible (over calm) and honest (over smart) technologies. Those are the types of values that emerge when professionals (e.g. engineers, data scientists, designers, decision-makers, executives) wander outside their practice, apply critical thinking to uncover dishonest behaviors, and use fictions to take decisions that consider implications beyond the scope of the “user” and the “task” to automate.

I believe that the organizations in the business of automation that maintain the status-quo and do not evolve into a business of trust might eventually need to deal with a corroded reputation and its effects on their internal values, the moral of employees, the revenues and ultimately the stakeholders trust.