For my record, below is the essay that appeared in Volume Quarterly, Issue 25.

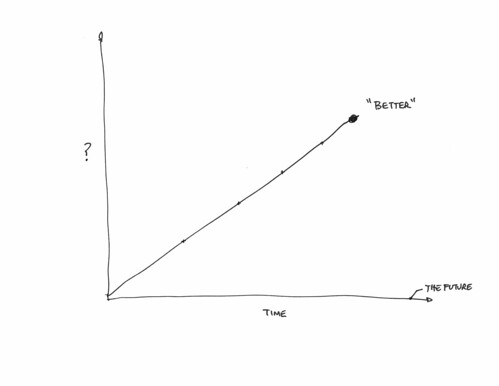

I just want to say that, from my perspective, right now — Design Fiction is quite useful as a way to say the things that one imagines and that might be seen as outrageous, or weird, or even “out of scope.” It’s a way of thinking about what could be in the quite near future because things *can change, even more than we would expect, quite soon. It does not necessarily take epic, big science, big politics or systemic upheaval to go from the world we have right at this moment, to a world in which the pulse and flow of life makes this moment seem arcane, old-fashioned or quaint. What ever happened to the dial tone? And complete sentences?

Julian Bleecker & Edwin Gardner

They say that the most convincing lies are the ones that stay “close” to the truth, probably this goes for good fiction as well. If fiction looses all relation with reality it becomes fantasy, escapism or utopia. To make good fiction, one needs a special relation with the truth. Telling a story about a possible world, or making a prototype of an idea that stay close to what we understand as reality and the everyday adds a degree of legibility. These things seem more possible than something that has no clear relationship to “today.” The truth of the present becomes a source that serves as a departure point. What we know today is where we evolve our understanding of how things are and how they could possibly be in the near future. It is the reality from which we pursue some small change in order to understand how things could be different from our expectations as to what the future will be. This might sound as a cryptic description of design, or science fiction. Or perhaps it is both: Design fiction.

Science fiction is the intelligent extrapolation of the present into alternate futures. These are futures that have a high degree plausibility which can be recognized and are legible because they have traces of the present. Interesting scifi futures are not just about progress, but about exploring the social and cultural as much as much as the technological. Design fiction is a practice of fiction that operates somewhere in between science fact and science fiction. Design as a practice of fiction is somewhat different from design proper. The constraints of science are defined by fact and by empiricism. That which cannot be measured, that which cannot be observed one way or another is considered irrelevant or non-existent by science fact. Science fiction, on the other hand, is expected to explore and probe those things that science fact dismisses. It is truly a kind of experimental art in this respect. Science fiction investigates possibilities extensively and with a wider set of allowances than science fact ever could. Add to science fact and science fiction the making and materializing rituals of design, which in the best of cases does not wait for something to be deemed “possible” or even reasonable before investing itself to imagining what could be, and you have a wonderful hybrid practice for extrapolating today into the near future. This is design fiction — a practice of making and creating that works as an interchange of concepts traveling back and forth between science fact and fiction.

In the scientific community mixing up these “genres” or disciplines is equal to blasphemy, or at least frowned upon. People who claim science fact as the practice idiom in which they do their work would never really say that they imagine things beyond “fact.” Certainly they enter into a sort of science fiction, which they might describe as speculating and “brainstorming.” This is a kind of science fiction that is made legitimate by calling its result hypotheticals, or by explaining these speculations as “theoretical prototypes”, or “just ideas” as if to say, “I know this is silly and not really possible, nevertheless..” These are explanations that are like perimeter alarms going off around disciplinary turf, indicating that we’re beginning to breech the hard, well-policed border between the proper work of science fact and the murky terrain of science fiction.

In a similar way there are science fiction idioms that define the boundaries of the genre. For example, “hard” science fiction. In this case “hard” refers to the rigor and the hard-set scientific principles necessary to support the accuracy of any science content within the story. Hard science in fiction must be explainable by extrapolations of present science fact. Hard science fiction is the perimeter alarm from the other side, as science fiction makes incursions into the knowledge and truths of science fact. One could say that when science fiction comes close to present-day reality, or state of the art technology it transforms into another “in-between” genre like a “technothriller” instead of “scifi”. It’s close enough to the present day, to the quotidian that it is no longer precisely fiction. This is the way that science fiction extrapolates and speculates based on the present, but perhaps more importantly in the scifi novel or film these extrapolations are worked out at the scale of society. This is how science fiction can have a direct impact on the human condition. The characters and the narrative are provided with a playing-field in which new dynamics of existence unfold into persuasive thinking exercises that, at some level we all engage on. The best science fiction makes us think about the future and our place in it.

Despite the boundaries and perimeter alarms, ideas, people and objects travel between disciplines and leave their traces. With science fact and fiction this is no different. Design fiction lives in between the disciplinary perimeters and it makes this exchange productive. This interrelationship between science fact and science fiction is very important. It reveals how culture circulates, especially the formation of ideas, knowledge and their object proxies. Which ideas get to circulate out in the world and why? How do ideas obtain their “mass” and accumulate attention and conversation. What about the ideas that become sidelined and obsolete?

Following two examples we can get an idea what happens in this “in between” where the practice of designing fiction is at work. First we start at fact and see how it influences fiction in the production of Spielberg 2002 film Minority Report. Second we’ll look at fiction and how it influences fact, in the case of the development of Virtual Reality and Ubiquitous Computing (Ubicomp)[1].

Fiction follows Fact: Minority Report

[image: stills from Minorty Report’s Gestural Interface]

Between Philip K. Dick’s short story The Minority Report through to the Steven Spielberg production of a film based on that story, an interchange of ideas and objects took place. This happened through the activities of scientists in their labs, conversations with film directors, props makers and experts on the future, back through to special effects artisans working in their shops with their film production software. Following just a few of these linkages shows how easily science-fact and science-fiction swap ideas, properties and objects.

The story of Minority Report takes place in 2054 and follows inspector John Anderton (played by Tom Cruise) who works in at “Precrime” a police department specialized in solving murders before they happen, through apprehending criminals based on foreknowledge provided by three psychics called “precogs”. This foreknowledge can be extracted from the precogs brains in the form of moving images and sounds, in which Anderton searches for clues on where, when and who are involved in the crime to be committed. Anderton can manipulate (zoom, playback, pause, remove, pan, save, etc.) these images and sounds through a gestural interface. This gestural interface is a wonderful prototype of a ubiquitous computing future, where a database of sound and images are manipulated through orchestra conductor- like gestures, summoning and juxtaposing fuzzy snippets of what is almost about to happen.

In the production of Minority Report, the idea for such a gestural interface came from somewhere and at least in part from John Underkoffler, who was the film’s technical consultant. Underkoffler was a member of the Tangible Media Group at M.I.T., and had participated along with a panel of luminaries in providing some speculations as to what the future of Minority Report might be experienced based on their insights and their extrapolations of the current trends in the technology world. What was needed were some projections to help trace a vector from the present to the future of 2054, when the film takes place.

From a project at the Tangible Media Group called “The Luminous Room” were a number of “immersive” computing concepts that were drawn from some of the principles of ubiquitous computing. The principles are related to the idea that computers might become more directly integrated into the architecture of the environments that people occupy. Rather than manipulating them with a keyboard and mouse, people might use gestures for direct input.

The gestural control of the clue-construction device as a film element has a well-balanced mix of visual dynamics that will keep today’s science fiction film audience riveted, and legible interaction rituals that allow the audience to follow the gestures closely to develop an understanding of precisely what is going on, what is being manipulated and how bits of clue are juxtaposed and re-arranged as one might do with a puzzle. Special attention is placed on the precision of the gestures that Anderton uses in order to manipulate the fragments of video and sound — zooming in on a bit of imagery with hand-over-hand gesture; deleting a few things by moving them with a forceful and dismissive sweep into this interface’s version of today’s user interface trash can.

There’s more than the clue-construction device that Anderton uses, it is the longer bit of story that I want to highlight, and not just the instrumental technology. Not the story itself — the pre-murder. Rather, I want to highlight what the story does so as to fill out the meaning of the clue-construction device, to make it something legible despite its foreignness. It is a kind of science fact-fiction work that effectively tries out some ideas within a film’s narrative. It’s sort of like prototyping — sketching out possibilities by building things, wrapping them around a story and letting them play out as they might.

More formally, this is what David A. Kirby calls the “diegetic prototype.”[2] It’s a kind of technoscientific prototyping activity knotted to science fiction film production that emphasizes the circulation of knowledge and ideas. It is like a concept prototype, but since we are designing fiction the added property is a story into which the prototype can play its part in a way different from a plain old demonstration. The prototype enlivens the narrative, moving the story forward while at the same time subtly working through the details of itself.

“..scientists and engineers can also create realistic filmic images of “technological possibilities” with the intention of reducing anxiety and stimulating desire in audiences to see potential technologies become realities. For scientists and engineers, the best way to jump start technical development is to produce a working prototype. Working prototypes, however, are time consuming, expensive and require initial funds. I argue in this essay that for technical advisors cinematic depictions of future technologies are actually “diegetic prototypes” that demonstrate to large public audiences a technology’s need, benevolence, and viability. Diegetic prototypes have a major rhetorical advantage even over true prototypes: in the diegesis these technologies exist as “real” objects that function properly and which people actually use.” [3]

The film becomes an opportunity to create a vision of the future but, perhaps more important, to share that vision to a large public audience. In specific cases, such as the evocative “gesture interface” concepts Underkoffler introduced into the film’s story and its production design, ideas gather a kind of knowledge-mass. They become culturally legible and gain weight and currency. We “get” the idea of using conductor-like gestures to interact with our information technology because it is given to us through the film, it’s pre-science, the discussions that evolve in media and with friends, the formation of companies to further develop the ideas, bolstered on the cultural literacy with touch and gesture interactions, and so on. To gain cultural legibility takes more than a scientist demonstrating an idea in a laboratory. What is needed is a broader, context — such as one that great storytellers and great filmmakers can put together into a popular film, with an engaging narrative and some cool gear.

The follow-on to this science fiction film introduction of gesture interfaces to a large public audience are more gesture interfaces, each one staking out Minority Report as a point of conception, either explicitly or implicitly. It’s as if Minority Report serves as the conditions of possibility for more and further explorations of the possibility for gesture interaction — whether touchbased gestures, as in the Apple iPhone and other techniques, or free-space and tracking gesture interactions, like the Nintendo Wii, for example. This is not precisely the case: we are not interested in claims as to priority, ownership and who did what first. What is much more interesting is the brocade of activity that weaves in and through the fictional/factual special effects props of Minority Report.

[Image: Google ‘minority report’ search results]

[Image: CNN]

[Caption:]

In 2002, Minority Report was released, which we may describe as the diegetic prototype for the gestural interface concept. In this segment, CNN reports on the real-world prototype in the year 2005. The following years trace a knot of interpretations and reflections as the idea of a gesture-based interaction circulates and gains “idea mass” — the “Google” of “Minority Report Interface” the breadth of interpretations and the notion that moving ideas to their materialization can happen through the lens of fiction.

Fact Follows Fiction: HITLab

[Image: guy with VR glasses]

In the early nineties at the University of Washington the Human Interface Technology Lab, or HITLab was working quite hard on virtual reality (VR), a kind of immersive, 3D environment that, today, one might experience as something like Second Life. The technology had a basic instrumental archetype canonized in a pair of $250,000 machines (one for each eyeball) called, appropriately, the RealityEngine. With video head mount that looked like a scuba-mask, one could experience a kind of digital virtual world environment that was exciting for what it suggested for the future, but very rough and sparse in its execution.

One of the informal socialization rituals of acquainting yourself to the other members of the HITLab team — and to the idioms by which the lab shared its collective imaginary about what exactly was going on here, and what was VR. Anything that touches the word “reality” needed some pretty fleet-footed references to help describe what’s going on, and a good set of anchor points so one can do the indexical language trick of “it’s like that thing in …”

For the HITLab the closest thing to a shared technical manual was William Gibson’s novel “Neuromancer” which was encouraged to read closely before you got too far involved and risked the chance of being left out of the conversations that equated what HITLab was making with Gibson’s “Cyberspace Deck”, amongst other science fiction props. This is from a paper that Randy Walser from Autodesk wrote around the same time:

“In William Gibson’s stories starting with Neuromancer, people use an instrument called a “deck” to “jack” into cyberspace. The instrument that Gibson describes is small enough to fit in a drawer, and directly stimulates the human nervous system. While Gibson’s vision is beyond the reach of today’s technology, it is nonetheless possible, today, to achieve many of the effects to which Gibson alludes. A number of companies and organizations are actively developing the essential elements of a cyberspace deck (though not everyone has adopted the term “deck”). These groups include NASA, University of North Carolina, University of Washington, Artificial Reality Corp., VPL Research, and Autodesk, along with numerous others who are starting new R&D programs.”

The objects that authors like William Gibson craft through words are kinds of designed objects that help fill out the vision, inciting conversations, providing backdrops, set pieces and props. The Cyberspace Deck. Gibson wrote about it and it had a story that was compelling enough that it may as well be built. The written objects creates a goal line, a critical path toward the successful completion of the VR mythos. Together, the linkages that connect fact and fiction are ways of filling in that shared imaginary, which then knits the social formations of everyone and everything together. Bruno Latour would remind us that this is the socialization of objects. Technology is precisely the socialization of ideas via object proxies. You don’t need to look much further than this VR anecdote to appreciate how technology is always already the assemblage of social practices. It happens in the circulation of ideas and stories that draw in a multitude of perspectives, and ways of expressing the imagination, from circuit diagrams to galactic adventures.

In 2009 Paul Dourish and Genevieve Bell write “‘Resistance is Futile’: Reading Science Fiction Alongside Ubiquitous Computing.” This essay does something quite bold in that it looks at the collective imagination of the Ubicomp field (scientists, researchers, and so on but, curiously, not its objects and props and prototypes) alongside of the science fiction imaginary as seen through a number of science fiction shows (Dr.Who, Star Trek, Planet of the Apes, Blake’s 7 and Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy) that are arguably part of the shared history of Ubicomp researchers. They make an important argument in the context of design fiction that the narrative themes and cultural implications within the science fiction stories are properties that participate in design practices whether you like it or not. These themes are only in science fiction in their examples because they are largely ignored and considered irrelevant in most technological design practices. But allowing these themes to “participate” in technological design has value to the design practice and its methodology.

[Image:fanart – Star Trek Star Fleet Technical Manual, 1975]

[Caption:]

Fan art evolved to the point of speculating about the technical particulars of props from science fiction is found in these diagrams from The Star Trek Star Fleet Technical Manual, by Franz Joseph (1975) a technical artist and designer who worked during the day for General Dynamics. Joseph’s technical fan art translates the science fiction into a kind of science fact to the extent that he considers the materialization of the various artefacts. Patterns are given for constructing the Star Fleet uniforms worn within the science fiction. Architectural diagrams are drafted for the space ships. Regulation patterns for fleet colors and banners are specified. Organization charts for command and operational hierarchies are mapped out. There are design schematics for technologies that only exist in the science fiction.

Culture “embeds”, as it always must. There is no pure instrumentality in technologies, or sciences for that matter. The arrival of an idea, or concept, or scientific “law” comes from somewhere, never “out there” but always rather close to home. Bell and Dourish are telling us this in their essay using the particular example of Ubicomp. Ubicomp endures its own cultural specificity and debt to things like desire for specific near futures that are given an aspiration portrait in, first of all, the imaginative vision of Mark Weiser[4] and, second of all, some good old fashioned near future science fiction. They are both techniques for connecting the dots between dreams, the imagination, ideas and their materialization as “shows” that talk about the future, exhibit artifacts and prototypes. Those “shows” can take the form of a television production, film, laboratory activity, research reports, annual gatherings of die-hard fans at Ubicomp conferences and Star Trek conventions, and so on. They’re all swirling conversations that are expressions of a will, desire, creativity and materiality around some shared imaginaries.

Bell and Dourish are reminding us that the implications of culture are not something that happens after design. They are always part of the design. They are always simultaneous with the activity of making things. The culture happens as the design does. This is in every way what design is about. It is less about surfaces and detailing, and perhaps only about making culture. Making culture is that things-designed become part of the fabric of our lives, shaping, diffracting, knitting together our relations between the other people and objects around us. Making culture is something that engineering has so effectively and, at times, dangerously pushed out of view, which is why design should participate more actively and conscientiously in the making of things. Engineering tends to start with specifications, assuming that terse instrumentalities and operating parameters evacuate the cultural implications. Design brings culture deliberately. It’s already there, this culture thing — design is just able to provide the language and idioms of culture, a language which engineering has long ago forgotten. Social or cultural “issues” or “implications” are always already part of the context for design. These are not issues that arise from a technical object once it is delivered to people, as if this act of putting an object in someone’s hands then somehow magically transforms it into something that, now set loose to circulate in the wild cultural landscape, produces “issues” or creates implications. It is the case that the social or cultural questions are always already part of the operational procedures of the engineering work, never separate. One need only look at specifications and read closer than the surface to see where an how “culture” is the technical instrument. Despite the fact that it looks like a bunch of circuits and lifeless plastic bits, there is culture right there.

References:

———-

[1] Ubicomp: (ubicomp) is a post-desktop model of HYPERLINK “http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human-computer_interaction” human-computer interaction in which information processing has been thoroughly integrated into everyday objects and activities. In the course of ordinary activities, someone “using” HYPERLINK “http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ubiquitous” ubiquitous computing engages many computational devices and systems simultaneously, and may not necessarily even be aware that they are doing so. This model is usually considered an advancement from the HYPERLINK “http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Desktop_environment” desktop paradigm and also described as pervasive computing or HYPERLINK “http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ambient_intelligence” ambient intelligence

[2] Deigesis: a narrative or plot, typically in a movie

[3]David A. Kirby, “Future is Now: Diegetic Prototypes and the Role of Popular Films in Generating Real-World Technological Development” forthcoming in Social Studies of Science, a journal.

[4] Mark D. Weiser (July 23, 1952 – April 27, 1999) was a chief scientist at HYPERLINK http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PARC_%28company%29 Xerox PARC in the United States. Weiser is widely considered to be the father of HYPERLINK http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ubiquitous_computing ubiquitous computing, a term he coined in 1988. Mainly through his piece HYPERLINK The Computer for the 21st Century” – HYPERLINK Scientific American Special Issue on Communications, Computers, and Networks, September, 1991

! – This essay is primarily based on “Design Fiction” by Julian Bleecker published online at the Near Future Laboratory: HYPERLINK “http://www.nearfuturelaboratory.com” www.nearfuturelaboratory.com

” by Charles Yu. Great good barely science-fictional novel here. Really a story about loss and our human nature to regain what has gone and re-do and re-play our lives. Its about travel through time but along the way you get to enjoy some good design fiction swerves and curves. A few good things to think about, ponder over and imagine. I particularly enjoy the way that time-travel is intimate with story-telling in the novel’s world — its a kind of technology and industry (military-industrial-narrative-entertainment complex) that goes along with it: conceptual technology, chronodiegetics and diegetic engineering! I’d say this is a strong-recommend. Pretty much no spoilers below.

The guy reaches his stop and gets off, leaving his news cloud behind. I love watching the way these clouds break up, little wisps of information trailing off like a flickering tail, a dragon’s tail of typewriter keys and wind chimes, those little monochrome green cloudlets, a fog of fragments and images and words. On busy news days, the entire city is awash in these cloudlets, like fifty million newspapers brought to breathing, blaring life, and then obliterated into a sea of disintegrating light and noise.