A fix to keep a door from clanging against an adjacent utility pole. Observed in Seoul, South Korea.

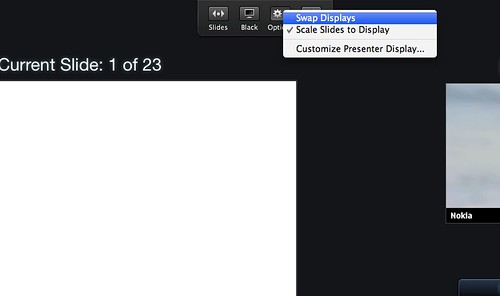

It’s too bad that the measure of results often must translate to quantities or business-y things, like numbers of meetings obtained or pages of PowerPoint presentations. Decanting often rich, qualitatively substantial ideas into boxes and “slides” and “decks” sloughs off so much richness that all that was learned often evaporates. The miscommunication is tragic in such instances. When asked for “the presentation”, I’ve taken to doing the electronic email version of a *shrug* — sorry, no “deck”. We can chat. I can send you some object-thing-embodiments-of-principles..if you like. If you want to stare at words, well..

The culture of PowerPoint is best described as a social disease. I don’t mean to gripe too much — it’s not a new thing, and it isn’t only a reaction to conditions as they exist for the Laboratory right now. The culture of the deck has been around us since the days at the advertising agencies and brand marketing agencies during the last cycle — where there were entire departments who did nothing but make presentation decks. Ugh. Can you imagine?

The Measure of Reality has been an obsession since I fully comprehended the made-up nature of reality, I suppose while thinking about the social and cultural parameters of science while over-educating myself. It’s good stuff — I’m not complaining — and it makes it positively frustrating at times to communicate something where you know that everything depends on how you communicate and not only the idea living in your head. No matter how much you believe in it, you have to materialize it in such a way that other people believe in it, too. You need to enroll people in your vision to the degree that they suit up and follow.

In the world of things the Laboratory works on — weird gizmos, gadgets and devices — this becomes particularly difficult when the basis for describing a design-led vision avoids touching on technology-specific features. For some reason lists of features are legible to accountants and engineers who often have the keys to the car and decide what gets done. Here, we wouldn’t offer something up that starts with a bit of technical kit — an augmented reality sensor array or whatever — and then build around that. We would start with a peculiar people-centric platform of experience — say, an otherworldly city guide as we did for the first analog edition of the Drift Deck and as Laboratory Associate Platinum Class Jon Bell is doing for the second digital edition of the Drift Deck. Our conceit has been that experiences for people offer a richer, more meaningful and legible way of creating new stuff. Innovating, only not by stacking lists of features and parts and stuff — but at least by starting with ways of creating opportunities and experiences that lead people in new, unexpected directions. That make space for experiences that go beyond expectation. Basically creating new user experiences. I don’t think you do that just by creating new features and bolting on new technologies.

When I first wrote the draft of this post, it came to mind when the folks at Tenyagroup asked permission to use a photo (that wasn’t even mine, but whatever..) I looked at their short article and found it intriguing. At one point they say:

..great brands change the game by changing the customer, not by changing the product. They become new platforms of opportunity for a new kind of customer, freshly empowered.

Those are weird words not really in the Laboratory lexicon, but somehow it makes sense. The “changing the customer” part might be stated plainly as: offering new sorts of interaction rituals and behaviors. Merely adding a bit of technology does not translate that technology into a necessarily compelling experience. It’s back to the doorknobs joke — if you can’t translate the technology into terms and experiences legible to a normal human, you’ve just stacked yet another unnecessary ornamentation on top of everything else.

This is all swirling around an argument not to design for features lists.

For brand builders, the following definitions of “features” might be useful:

Feature – Evidence of unfinished design.

Feature – The absence of brand vision.

Feature – Fear of freeing the customer–and raising him/her to the next level.

Feature – Footprint of the committee: more is less. As a rule, good design minimizes features and maximizes customers.

(inspiration via http://tenayagroup.com/blog/2009/02/21/customers-drive-brand-growth-not-features/)

Why do I blog this? This has been sitting in the Drafts pile for 18 months and I felt it was time to just post it before it got lost to some kind of data backup failure. But, I am continuing to hunt down ways of putting design-for-people as a guiding principle ahead of just adding meaningless features. Sometimes I see ideas from powerful decision-making people that basically lists the technologies du jour as specifications for what should be made. It’s infuriating — which is entirely my fault. I wish I had the techkwondo to flip that for real, and do so in an elegant way that helps people see the trouble of trying to stick doorknobs on everything they see. Also — trying to cohere some thoughts and scraps for the upcoming Device Design Day later this month.

Continue reading Features Aren't A Measure Of Innovation