Just a super short set of notes from Steven Johnson’s book, Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation . I don’t have anything too much in-depth mostly because it’s a fast read, when I found time to read it, and it made me squirm uncomfortably. There was not much that made me stop and smile although I did quite a bit of exasperated sighing along the way.

. I don’t have anything too much in-depth mostly because it’s a fast read, when I found time to read it, and it made me squirm uncomfortably. There was not much that made me stop and smile although I did quite a bit of exasperated sighing along the way.

I think this is because Johnson chose to muddle the study and insights of biology and evolution with the activities of humans following their curiosity, their inspiration to make things, their will to create enterprises, their greed to overwhelm their competitors and make fortunes by whatever means necessary, their hubris, their social-political ambitions, their desire to leave a statue of themselves behind — whatever it is that drives individuals to build and create. Using the study of organisms, biology, the ocean reefs, species evolutions, ecosystems — all of these things as metaphors for creativity, innovation, good ideas in the making — well, that’s just problematic in my mind. You exhaust the really interesting work right out the tailpipe of your story and you’re left only with this pre-existing framework of biology and ocean science and these things to explain how Marconi’s innovations with radio. At some point the analogy becomes the story itself — it’s not like the innovation work *is like* ocean reefs accreting new material. The innovation work is a reef, with new ideas building upon old ones like so. At some points in Johnson’s story human endeavor to make new things and come up with new ideas lose out to the simplicity of the science analogy. Human ingenuity becomes the same thing as the study of species, reefs and other “up and to the right” style evolutionary stories. This makes for a good children’s allegory or grammar school analogy — or a good cocktail party explanation of the irreducibly complex activity of “innovating.” But, it makes a book-length treatment of the complexity of creativity fairly gaunt at best.

Somewhere muddled up in there is an argument that Cities breed innovation because people are so packed in together (like an ocean reef?) and ideas propagate more efficiently in density, which may be the case — but it feels like a vague generalization. It’s easy to get into an argument about whether NYC is more creative than Los Angeles, for example — and things quickly spiral out of control.

Perhaps the best part of the book is the last sentence which might be the argument and even the framework for how the book works — forget all the biology analogies. Just this tweetable little nugget.

Go for a walk; cultivate hunches; write everything down, but keep your folders messy; embrace serendipity; make generative mistakes; take on multiple hobbies; frequent coffeehouses and other liquid networks; follow the links; let others build on your ideas; borrow, recycle, reinvent. Build a tangled bank.

Had Johnson followed the walks of those innovators he was curious about, followed them along their mistakes and noted the ways they borrowed, recycled, reinvented he could have done away with the silly biology analogies. It’s all right there in the hands-on work that’s going on — there’s no need for a big, grand, one-size-fits-all theory about how ideas come to be and how they circulate, or don’t circulate and how they inflect and influence and change the way we understand and act and behave in the world. That’s the “innovation” story — or the way that *change-in-the-way-we-understand-the-world* comes about story.

What I think Johnson is trying to do is in fact deliver some material for that cocktail party conversation — to instill in readers’ minds the idea that good ideas don’t just happen in isolation. They happen because of this idea of the “adjacent possible” — Stuart Kauffman’s idiom describing the multiple possibilities for what can happen because things (science-objects in Kauffman’s notion, like molecules or elements that lead to new science-objects; idea-objects in Steven Johnson’s notion, like steam engines and wine presses that lead to new idea objects like locomotives and printing presses) are proximate. Here’s how Johnson introduces it to us — and he’s not really reminding us that he’s taking a scientific thesis by a guy and using it to describe how innovation works.

“The scientist Stuart Kauffman has a suggestive name for the set of all those first-order combinations [molecules becoming DNA, e.g.]: “the adjacent possible.” The phrase captures both the limits and the creative potential of change and innovation. In the case of prebiotic chemistry, the adjacent possible defines all those molecular reactions that were directly achievable in the primordial soup. Sunflowers and mosquitoes and brains exist outside that circle of possibility. The adjacent possible is a kind of shadow future, hovering on the edges of the present state of things, a map of all the ways in which the present can reinvent itself. Yet it is not an infinite space, or a totally open playing field. The number of potential first-order reactions is vast, but it is a finite number and it excludes most of the formst that now populate the biosphere. What the adjacent possible tells us is that at any moment the world is capable of extraordinary change, but only certain changes can happen.”

What could come to be in the world of combinations of molecules and atoms and so forth that happen to be swirling in the same goo — is the basis for Johnson’s thesis about what could be in the world of accreting and “exaption” of ideas. The adjacent possible is meant to describe the what could come to be based on the coexistence and proximity of materials. Things bump into other things and come to form new things under certain conditions. There’s not one possible outcome, but multiple possibilities.

What Johnson does is confuse this for the way that ideas — which are not molecules or atoms swirling in a primordial goo — evolve into possible “shadow futures.” Will and cunning and gile and ambition and money and access to money — these and many other non-biological factors shape how good ideas come to be. ((As well as horrible, wretched, resource-wasting ideas.)) I mean — this is a troubling way to make an argument from the get-go. I don’t think you can just willy-nilly take a thesis from biology (or hypothesis, or lens, or view of how things work) and then use it to describe something that is never as pure as what we understand “nature” to be or “natural history” — he is not creating a story that describes what happens in the world of ideas, spun and spurned by people with bodies, situated in time, space, culture and society and struggling for credibility and authority . And that’s just a problem. The coordinates and biases and ways-of-knowing are all wrong at some level. The units are way off. It’s an allegory at best that misses 99% of the mishegoss of creating knowledge and meaning; an analogy that basically filters out all the work of humans interacting in a different way than the way that molecules and atoms interact. It’s another one of those kinda annoying uses of science to explain society which starts you down the path of immediately assuming that science isn’t society by other means, or that science isn’t already a social enterprise or — worse — that science has it all figured out.

. And that’s just a problem. The coordinates and biases and ways-of-knowing are all wrong at some level. The units are way off. It’s an allegory at best that misses 99% of the mishegoss of creating knowledge and meaning; an analogy that basically filters out all the work of humans interacting in a different way than the way that molecules and atoms interact. It’s another one of those kinda annoying uses of science to explain society which starts you down the path of immediately assuming that science isn’t society by other means, or that science isn’t already a social enterprise or — worse — that science has it all figured out.

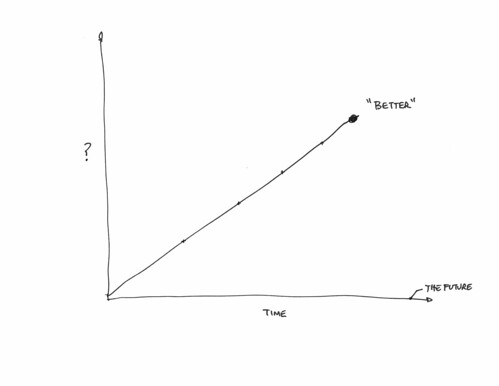

Anyway — I got suckered in because the book has the word “innovation” in it. These sorts of books with titles that are didactic are suckers bait. Its got this funny title about being a “natural history” of innovation and that seemed polite and humble, rather than prescriptive like a lot of business books tend to be. (“10 Steps to Improving Your Organizations Innovation Prospects!” — or things like that.) But then it’s less humble when you realize that this is The natural history of innovation that’s been written. N’ah — I know he’s probably being provocative with this title. But, still — I found it a bit bold. Because inside is not a natural history at all, but rather an argument made through a number of examples. The argument is to dispel the notion that good ideas — ideas that make incremental changes in the graph, making things move up and to the right to a greater or lesser degree — come from a guy sitting around by himself in a lab or basement. Rather, good ideas come about because of their proximity to other, perhaps disparate activities — other intriguing things happening nearby. Johnson’s prop is the ocean reef — and perhaps this is the joke in the title because the reef is understood to be something natural (as if) and therein lies the natural character of innovation.

Couple of notes, so long as they were jotted down while I was reading this:

He has a curiously muddled appendix of good ideas at the end, with the electric battery (1800) — every good idea has a date — sitting alongside of sunspots (1610), as if sunspots were a good idea as opposed to an observation that becomes relevant and topical. I can only imagine that these are intractably complex things that are as dense a knot of activities both purposeful, willful and incidental as one can imagine. Yet here they are rather cavalierly given a sentence or two and a date stamp as if they appeared as a good idea suddenly.

He diverts detractors to his approach of going broad and shallow by saying that there is value in surveying and drawing conclusions from many short case studies and drawing four quadrant graphs that even further simplify the points. The alternative is to be deep and thick, or to go into the laboratory — talking to people to suss out the meaning and history and all that of technology. The broad and shallow perspective is not as thorough. It’s a gloss, but even worse — it’s not substantive and opinion at best. This is fine, but the reader never really knows what they’re losing in the trade.

The argument is an engaging story — a good story. It’s an argument insisting on a POV and a thesis about an intractably complicated social/cultural/political/economic entanglement that cannot possibly be distilled to a core, to an essential character and way-of-being except in the most simple ways which never can possibly be much more than a fairy tale useful only for the most basic of explanations you might use to tell a child why the sky is blue, or as an allegory — it’s certainly not a history, natural or otherwise.

If you want to hear a really irksome panel discussion with Kevin Kelly and Johnson, check out this Radiolab podcast: What Does Technology Want?. It’s curious to me that Johnson and Kelly seem to jump on Robert Krulwich to the point of basically saying — “what’s wrong with you? don’t you believe in technology’s autonomy?”

Continue reading What Innovation