So I have just returned from a multipurpose trip, one of whose purposes was to see the Tom Sachs exhibition at the Park Avenue Armory in New York City. This is the Tom Sachs show done in collaboration with NASA (and a crop of creative partners, like Creative Time, but that’s less typical than collaborating with NASA.) Much like his studio’s “Space Program” exhibition from a few years ago at the Gagosian in Beverly Hills, this exhibition takes as its theme space travel only this time instead of a mission to the moon, it’s a mission to Mars. The specifics of the work is mostly in the details of it’s preparation and a bit in its demonstration. The way Sachs’ studio runs — as best as I can discern from the artist talk — is quite thorough. The studio treats the mission quite playfully-seriously. So, much like astronauts may work quite hard on physical fitness and the like, the studio does as well — doing morning runs, coordinated limbering exercises, weights and the like. In the videos showing the preparation work, you see the studio in appropriate era fitness clothing doing exercises idiomatic of the sort you might see in the context of astronaut preparation. They’re doing it all with a playful spirit, but evidently it’s taken quite seriously.

The script to the exhibition was fairly close to the “Space Program” — at least insofar as the space travel bits. The exploration and excavation of the martian surface had some variations of course, but otherwise it was quite similar. It’s the same Saturn V rocket and the astronauts (again, both women) travel in the LEM — I suspect it’s the exact same one as “Space Program”, but it is a lunar excursion module, rather than some speculative martian excursion module.

The collaboration with NASA brings a very intriguing “design fiction” angle to the project insofar as the studio, according to the artist talk, worked quite closely with NASA scientists. To what ends, I’m not entirely sure of course, but the collaboration is there. In a way this is somewhat like Kubrick working with the rocket scientists of his era in order to understand the needs and constraints of rocket ships basically before there were rocket ships.

Sachs enjoys the patina of bricolage so his interpretations have a certain hand-made-ness and found-materials-that-are-perfectly-fine-ness to the work. This sculptural quality makes them deliberately playful. I find this more than simply playful though, but I can’t quite get to the bottom of it. It’s ingenious in a certain way. Ingenious craftwork. To use a basketball as the main living module of the Odyssey from 2001 is fun at the same time that is subverts the tendency I might have to make the model indiscernable from the real thing, at least as far as the material goes. This is just my own perception and interpretation of this choice, but I feel like it’s something I’d like to learn from. ((Oftentimes we’ll make thins with the same level of resolution and fidelity one would expect from a “real” object. I can think of various reasons and rationales for subverting this “reality” as a way to enter into a different set of conversations — perhaps to reflect more of the craftwork, the individuality of an idea or object, or to bring in a conversation about artisinal qualities.))

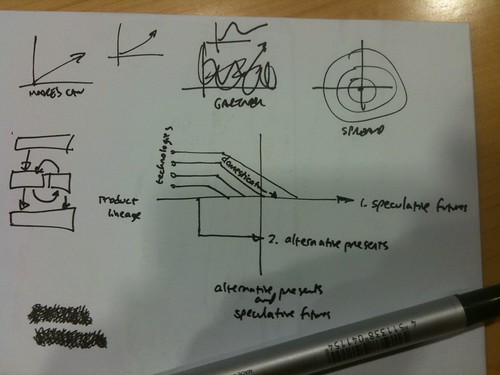

One thing Sachs said during the artist talk that was nice to hear — not a surprise, just something that brought into focus perhaps one of the reasons that I enjoy his work, aside from the fact that its about golden-era space travel — was this: “I see no problem synthesizing science with fiction”. So this statement explicates his own approach to the work and captures that relationship with ‘real scientist’ and the interpretative qualities of his demonstrations and sculptural constructions together with my own interest in designing with fiction.