A couple of years ago, in a small discussion group while I was teaching at USC, Paul Dourish presented an early draft of a paper he and Genevieve Bell were working on. If you read this blog, you probably know the paper. It’s called ” ‘Resistance is Futile’: Reading Science Fiction Alongside Ubiquitous Computing.” It’s a wonderful paper for a number of reasons. What is most wonderful, for the purposes of this dispatch, is the clever way the paper creates a conceptual linkage through science-fiction-ubiquitous-computing. The idea that “science fiction does not merely anticipate but actively shapes technological futures through its effect on the collective imagination” and “Science fiction visions appear as prototypes for future technological environments” — well..this is really juicy stuff.

(Their paper is generally around in draft form, for better or worse, thanks to the Google. It’s forthcoming in the Journal of Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, which is generally only readily available to academics and researchers with access to pricey journals.)

Paul asked myself and a number of people to consider writing something like a response or further considerations kind of thing that could sit alongside the article’s publication. I started in on this last summer. Ultimately, for reasons that became clear as I was writing the essay, I decided that there would be more to be said than would be tolerated in a staid, expensive, peer-reviewed academic journal, never mind that there could possibly be a wider conversation beyond the ubicomp community as my thinking ran into film, design, fan culture and unanticipated other places.

The short bit I wrote ended up as “Design Fiction: A Short Essay on Design, Science, Fact and Fiction.” It’s available as a downloadable PDF, out there in the on The Near Future Laboratory’s modest puff of Internet Cloud. (Its various incarnations as slideshows and talks can be found here on Slideshare.)

What is this all about?

Extending this idea that science fiction is implicated in the production of things like science fact, I wanted to think about how this happens, so that I could figure out the principles and pragmatics of doing design, making things that create different sorts of near future worlds. So, this is a bit of a think-piece, with examples and some insights that provide a few conclusions about why this is important as well as how it gets done. How do you entangle design, science, fact and fiction in order to create this practice called “design fiction” that, hopefully, provides different, undisciplined ways of envisioning new kinds of environments, artifacts and practices.

I don’t mean this to be one of those silly “proprietary practices” things that design agencies are fond of patenting. This is much more aspirational than that sort of nonsense. It’s part an ongoing explanation of why The Near Future Laboratory does such peculiar things, and why we emphasize the near future. The essay is a way of describing why alternative futures that are about people and their practices are way more interesting here than profit and feature sets. It’s a way to invest some attention on what can be done rather immediately to mitigate a complete systems failure; and part an investment in creating playful, peculiar, sideways-looking things that have no truck with the up-and-to-the-right kind of futures. Things can be otherwise; different from the slipshod sorts of futures that economists, accountants and engineers assume always are faster, smaller, cheaper and with two more features bandied about on advertising glossies and spec sheet.

Design Fiction is making things that tell stories. It’s like science-fiction in that the stories bring into focus certain matters-of-concern, such as how life is lived, questioning how technology is used and its implications, speculating bout the course of events; all of the unique abilities of science-fiction to incite imagination-filling conversations about alternative futures. It’s about reading P.K. Dick as a systems administrator, or Bruce Sterling as a software design manual. It’s meant to encourage truly undisciplined approaches to making and circulating culture by ignoring disciplines that have invested so much in erecting boundaries between pragmatics and imagination.

The American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, a professional science fact organization, considers the way Arthur C. Clarke and 2001: A Space Odyssey has contributed to space travel in their April 2008 newsletter. Well worth the read for revealing the entanglements of science, fiction and fact.

AIAA Houston Section newsletter, April 2008.When you trace the knots that link science, fact and fiction you see the fascinating crosstalk between and amongst ideas and their materialization. In the tracing you see the simultaneous knowledge-making activities, speculating and pondering and realizing that things are made only by force of the imagination. In the midst of the tangle, one begins to see that fact and fiction are productively indistinguishable.

Design is about the future in a way similar to science fiction. It probes imaginatively and materializes ideas, the way science fiction materializes ideas, oftentimes through stories. What are the ways that all of these things — these canonical ways of making and remaking and imagining the world — can come together in a productive way, without hiding the details and without worrying about the nonsense of strict disciplinary boundaries?

How did William Shatner change the world? If you’re wondering, allow yourself to enjoy the remarkable, campy and entertaining documentary (of sorts) called

How William Shatner Changed the World

Science fact and science fiction are given a good stir in this show, which explores “the science behind the science-fiction of Star Trek.” Whereas Joseph’s technical fan art translates the science fiction into a speculative science fact, this short, campy docu-film follows William Shatner, playing William Shatner, trotting about the world pointing to the ways that Star Trek influenced real, science fact in the world today. We see interviews with real people — scientists and technologists mostly — who have anecdotal stories about how Star Trek inspired their breakthrough ideas, or provided a backdrop near future imaginary for their aspirational thinking.

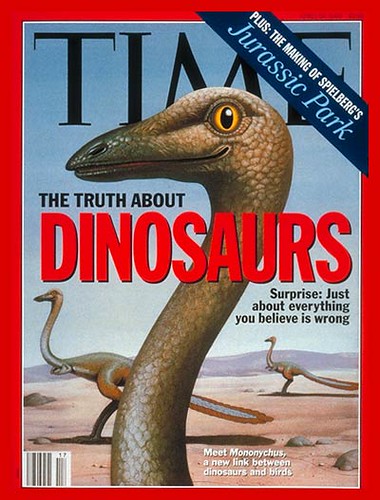

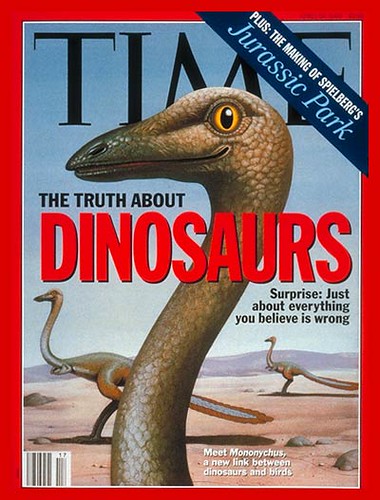

The intermingling of science, fact, fiction, production is exhibited on this

ancient cover of Time Magazine, 14 years ago during the last

Jurassic Park (the movie) dinosaur craze. (Read this closely: it contains truth, a science, a film, a correction to your grade school knowledge, and special effects made props/prototypes of science.) Curious crosstalk between science fiction and science fact, genetics, science politics and museum exhibition design was energized by this Spielberg/Crichton/Horner collaboration. Horner? Who? He is the swaggering outlaw paleontologist hired on by Spielberg to serve as a technical consultant – who was also the basis for the thinly veiled Sam Neil character called

Alan Grant in the film. He held a controversial theory that dinosaurs were more bird-like than previously thought. This was a minority view in the paleontology (the science) community. But, with the film and his participation as a science consultant, it was a view that became bolstered way behind the possibilities of peer-review, patient experimentation, annual science convention discussions and scholarly arguments. If you need more convincing that the science of fact and the science of fiction are all tangled up, and can be productively intertwined, read on.

Aspire, imagine, make the future you want.

I’ve written more about this, from some conversations with friends and colleagues last fall. It’s here, in this PDF called “Design Fiction: A short essay on design, science, fact and fiction.” It started at that discussion group with Paul in 2005 or 2006, and evolved into something I presented last fall at the Design Engaged ’08 workshop in Montreal, then the SHiFT 08 conference in Lisbon last October, then at the Moving Movie Industry conference, finally at the O’Reilly ETech 2009 conference.

Subsequently, this topic has been taken up in a variety of forms and venues. Bruce Sterling has a wonderful essay on the topic in the ACM Interactions journal. And I organized a panel at South by Southwest 2010. with Bruce, Sascha Pohflepp, Stuart Candy and Jake Dunagen with Jennifer Leonard doing an excellent job of wrangling and moderating. (The video should be available in a month or so from mid-March 2010.)

By request, here is a Design Fiction Printable Edition that will print on normal, human paper, to scale on 8.5×11.

Why do I blog this? A written kind of design provocation. For the last several months, there’s been a bit more word cobbling than wire soldering. The two practices contribute to the same set of objectives, which is to make and remake the world around us, provide new perspectives and evolve a set of principles that help make the making more imaginative, more aspirational.

I should also add that, when I was writing my master’s thesis on Virtual Reality some time ago (it’d have to be ‘some time ago’ for that topic), I wrote about science fiction meeting science fact, which was some of the earliest inspiration for this work, shared by the laboratory imaginary of the grad student “cyberfreaks” in the University of Washington HITLab and our reading/re-reading of Gibson’s Neuromancer during the early 1990s. Not just Neuromancer but all kinds of science fact/fiction. The simultaneity of the science fiction and the military science fact that was the first Gulf War. I wrote about that, too, because I was being taught by the guy who made that military technology, which was an unpleasant experience, but one from which I learned a great deal about how fact and fiction can swap properties. That same curiosity led to further interest in visual stories and their role in understanding and making sense of the world around us, especially in science fiction film and video games. I wrote a dissertation on this, studying with Donna Haraway, err..when I was a young lad in 1993-95. Therein was a chapter on Jurassic Park as simultaneously science fact and fiction. We had plenty of lively discussions specifically on this film. (Sarah Franklin was visiting at UCSC then and wrote some really amazing stuff about science fiction and genetics out of that, back in the late 90s that appears in “Global Nature, Global Culture.”) There was a seminar paper I did on “Until the End of the World”, looking at the Sony Design concepts Wim Wenders used to create a compelling science fact within the science fiction diegesis. In there was one of the earliest bits of video game commentary (SimCity 2000) from a critical theory perspective, not that I care about ordinality, but some folks seem to. There was a chapter on the SGI Reality Engine, ILM and Special Effects in science fiction (mostly Jurassic Park, which brought me to David Kirby’s early work – he’s the guy who coined this phrase ‘diegetic prototypes’, btw) and science fact showing the techniques and technologies that allow media to cross from fiction to fact. And so on. In many ways, this essay is a continuation of these interests and one I share with a great deal of friends, colleagues and complete strangers, I’m sure. Lots of people are playing around in here, excitedly and eagerly swapping ideas and stories. It’s a conversation that’s usually quite energetic and fun. If the ideas herein intersect and entangle with yours, it means you’re a healthy, creative individual, aspiring for a better near future we all hope to one day to live within. It’s a waste of my time to say things like — yes, I’m working on that. Yes, I have been working on this while you were in grammar school. And to do this every time someone mentions something you are also thinking on? That’s just preposterous. I used to do that with students, or point out to them someone who has also been working on something they think they have thought about for the first time. Inevitably, for the younger students who think they’re the only ones in the world who thought about such-and-so idea — they shrink and pout and get petty and don’t realize that they are in a world of ideas and their uniqueness is in the doing, not the clamoring to be Sir Edmund Hillary climbing that hill for the first time. That’s an ancient, sick model of intellectual and creative cultural production. It’s a world of circulation these days, with knots and rhizomes and linkages between lots of activities.

And that’s all I have to say about that.

Design Fiction: From Props To Prototypes

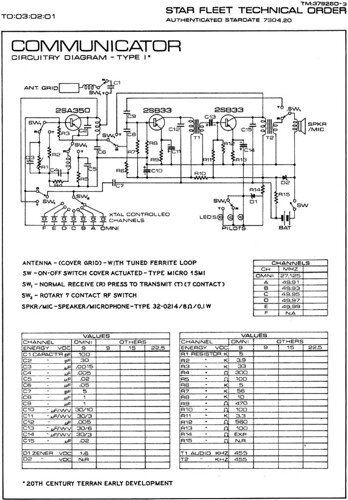

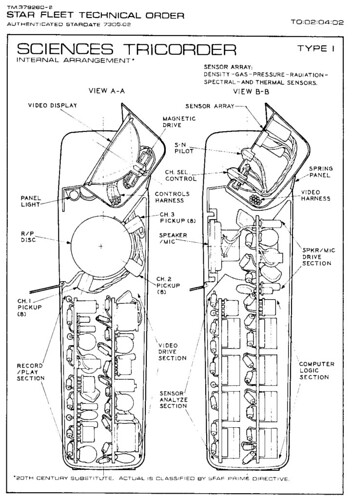

Franz Joseph was an expert technical draftsman working in the aerospace industry in Southern California during the heady, Skunkworks days of the 1970s. He started a special project — so advanced that it taunted belief. To call it “high tech” missed the mark by a few hundred years. The designs he was creating were beyond anything that had been done before. Laboring without the aid of today’s sophisticated illustration and computer-aided design systems, Joseph created a set of technical documents from the future, diagramming the details of technology so advanced and of such sophistication that the possibility of its existence teetered between fact and fiction. In 1976, it was a New York Times best selling book.

Joseph’s Technical Manual was a DIY shop manual for the science fiction world of Star Trek. It was a service and repair guide for tricorders, warp drive engine rooms and phasers. Joseph used his practical skills as a draftsman to extend the science fiction of Star Trek, telling his own sorts of stories about Star Trek through diagrams and schematics. In his drawings he played with our minds, entertaining us by blurring the broad line between fact and fiction.

A world with a Technical Manual has complex, fragile technology like tricorders and communicators and captain’s chairs that gets used by people and breaks down and needs repair. This is where we begin to realize that even technical diagrams of science fiction props can help us imagine these devices in use. Like buried artifacts found in an archeological dig from the future, we are left to fill in the gaps and knit together the stories suggested by the peculiar objects he drew. This is precisely what the Star Trek Technical Manual does quite powerfully and evocatively — it provides fuel for the imagination, making one think of a workbench somewhere in the year 2300 where a scrawny technician is puzzling over an intermittently functioning anabolic protoplaser or universal translator. Even fantastic technology has its ordinary, broken down moments.

Making the extraordinary ordinary is a recurring genre convention for science fiction. Because of its creative elasticity, sci-fi is able to make strange, implausible ideas mundane and everyday. The Technical Manual does precisely this, making the unreal seem real, even routine and plain.

A favorite viral example of this sort of reality effect is Michael Horn’s short film “Death Star over San Francisco” in which the Empire visits San Francisco during Fleet Week. We see the almost banal spectacle of an Imperial Trooper, 10 meters up on an AT-ST, poking his head out of the hatch and coaxing a passerby to toss up something they’ve dropped on the street, perhaps the keys to start the walker. Elsewhere we see a transport making a landing on the roof of an apartment building, as ordinary as anything you might see around San Francisco. The footage is rough and un-produced, with off-camera banter about barbecues and the rustle of wind on a microphone, clearing the way for us to imagine this as the product of an everyday tourist out and about during a holiday weekend. Another example of a similar kind of reality effect is filmmaker Floris Kaayk’s fictional documentary “Metalosis Maligna.” Kaayk “documents” a disease that arises from the widespread proliferation of metal implants. Visually, it plays tricks on us, forcing us to consider the reality of this condition. By using the conventions of the documentary — talking head experts, dramatic footage of people suffering horrific metal lattices protruding from their bodies, reserved voice over commentary, and so on — we are drawn into the possibility of this slightly sinister malignancy. Our willingness to accept a strange, otherworldly circumstance is heightened by the visually compelling short story.

The simple brilliance of these short films are similar to Joseph’s specific kind of diagrammatic creative story telling. They all teeter playfully between fact and fiction. These design fictions stretch the constraints of reality by taking the genre conventions of holiday videos or technical drawing and using these conventions to unassumingly fill out the contours of a slightly real, slightly fictional world. They allows for a different kind of engagement with a speculative idea. They draw it out, specifying it “as if” it were part of the world already. The Technical Manual, like “Death Star over San Francisco” lives somewhere in between speculation and materialization, in between an idea and that idea put in the hand to ponder over and consider. The fiction comes off the screen just a bit and gets closer to reality. The props become imminent, forcing one to consider to look sideways and consider that things could be otherwise.

In this way, the Technical Manual makes me think about new ways of making, creating and prototyping. It would be useful in the design world to prototype things in a way that help us imagine and wonder, and consider unexpected, perhaps transformative alternatives. Rather than the canonical technical prototype that operates as an engineering proof of feasibility, what about prototypes that are more like props? Material things, off the page and in the hand that help tell a story or start a conversation

This kind of prototype has nothing to prove — they do not represent technical possibility. They are prototypes that give shape and form and weight to one’s imagined idea. This is a kind of prototyping that couples the speculation inherent in design with the creative license of fiction and the pragmatic, imminent reality of fact. Tangible, materialized props that live in between fact and fiction and are both speculative and possible. They aren’t specifications for making, but they are specifications for imagining. These are prototypes that express possibility more powerfully than either fact or fiction could do if they were each left to their own intellectual and creative provinces. This deliberate blurring of fact and fiction is what we have been calling “design fiction.” Fiction borrowing from fact and thereby rethinking and re-imagining what may be possible.

Design fiction is a way to speculate seriously. It’s not quite brainstorming, nor is it ideating. It is design that tells stories. It creates material artifacts that force conversations and suspend one’s disbelief in what could be. It’s a way of imagining a different kind of world by outlining the contours, rendering the artifacts as story props, then using them to imagine. The prototyping activates the idea, giving it a few material features and some density, and forcing the refinement that comes from making something.

That in-between is what Joseph captures in his design-fiction mechanical drawings. The sparseness of words contrasts with the drawing details in such a way that we are forced to wonder about the implicit sophistication of these devices. Are they real? Where and when did this manual come from? These questions are forced upon the reader to interpret. This is the seduction of design-fiction at its best. The reader has to fill in the gaps and in the filling-in of gaps, we are made to imagine and wonder. And with these questions evolves a conversation that does not stop simply at the pragmatic, and does not dismiss as silly or impossible the fruits of imagining.

References:

Mike Horn Death Star Over San Francisco

http://vimeo.com/2587071

Star Trek Star Fleet Technical Manual, Franz Joseph (short link to book)

http://amzn.to/9L8JBW

Floris Kaayk’s Metalosis Maligna

http://vimeo.com/1192666

Marjolijn Dijkman Wandering through the future (2007)

http://www.marjolijndijkman.com/projects/view/1/132

Bruce Sterling’s Design Fiction Category List:

http://www.wired.com/beyond_the_beyond/category/design-fiction/

Near Future Laboratory Design Fiction Chronicles Category List

http://www.nearfuturelaboratory.com/category/design/design-fiction/

Near Future Laboratory Design Fiction: A Short Essay on Design, Science, Fact and Fiction

http://www.nearfuturelaboratory.com/2009/03/17/design-fiction-a-short-essay-on-design-science-fact-and-fiction/

SXSW Design Fiction Panel Audio

http://audio.sxsw.com/2010/podcasts/031310i_designFiction.mp3