The most recent — now a month or two old — issue of Volume Quarterly was on the topic of The Internet of Things. And within that was a small sub-volume of essays and articles on Trust compiled by Scott Burnham who has been running a project called Trust Design for Premsela which I understand to be The Netherlands Institute for Design and Fashion.

((The Laboratory seems to be a recurring guest in Volume Quarterly. We were in one a couple of issues back — their issue on The Moon.))

Scott started his project on Trust just as we in the Advanced Projects (then Design Strategic Projects) Studio at Nokia were beginning a project with the same name and some of the same questions. One of our questions was to understand what Trust is and how Design can somehow illuminate where Trust exists and its paths and relationships. When I say “illuminate” the image that comes to mind is one of a special detective’s forensic UV light illuminating something under specific conditions that would otherwise not be seen. Or, in those weird 1950s era medical treatments in which a subject drinks some wretched fluid or is injected with something that shows the paths of digestion or the networks of arteries when shown under X-Rays or something. (Maybe it isn’t wretched, but the thought gives me the willies for some reason.)

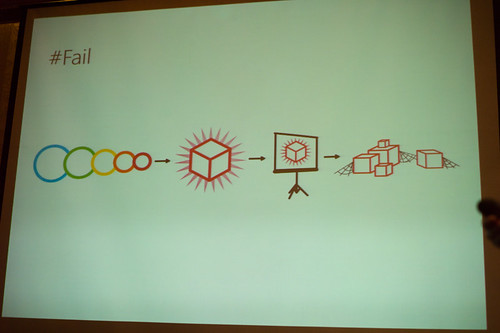

In any case there were many facets of the Design work we did in the studio, one of which was this Alarm Clock which was meant to operate precisely in this fashion — to focus our attention on a simple interaction ritual in which we were forced to consider characteristics of Trust.

The essay far below below was my contribution to the Volume Quarterly issue.

But first..

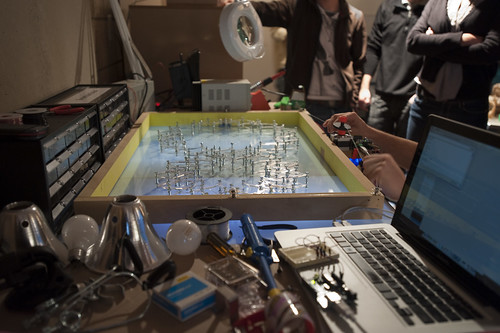

There’s a thing or two to add as well, that have more to do with this particular way of doing Design — or Design Fiction. The process of *making these clocks — which were made out of plastic and aluminum and electronics and solder and all that — was only partially about the specifications that determined how those things would be configured. Beyond those pragmatic, specified things were the ideas we sought to force to the surface — the concepts that we wanted to make ourselves address and consider directly. The preposterousness of the interaction ritual that the alarm mechanism forces was a deliberate way of compelling us to think and talk and design for this ephemeral social bargain called Trust. There was no way around it. We couldn’t lose ourselves in the geekery of circuit design; or choosing a color for the LED numerical displays; of obsessing over compound curves in the industrial design of the thing; or fetishizing any aspect of the “Design” as it is traditionally understood — a material instantiation of an already-accepted and well-understood object. There’s not much movement these days in Alarm Clocks. They are what they are and the variations come in things like…size. Like…color. Like…brand. Like…AM/FM or longwave. Like…number of alarms. Like…style. Like…box-y or round-y. Etc. You get it.

You’ll get stuck with those sorts of boring variations if you think about Alarm Clocks traditionally. Rather, thinking *not about Alarm Clocks but about waking up, and the rituals around it changes one’s approach. All of a sudden, you’re mucking with tradition. You’re getting people upset. You’re not responding to the client’s brief the way they expected. You’re not just doing color and materials variations.

Pfft. So what? Well — looking at things a little sideways is, for lack of a better moniker, advancing design. Advancing it beyond the expected. Doing the Fosbury Flop for Alarm Clocks.

The other thing to say about the project is that the making of the thing — all that plastic prototyping; all that circuit design; all that figuring-out-of-colors-and-materials; all that CNC machining; all that figuring out of tool paths; all that figuring out of firmware and interaction algorithms..why was all that done? Yes, of course — to make the thing *work, in the plainest sense. But, more than that — it was all done to do the Design. The making of the thing is *also a way of doing the Design of the thing. We didn’t figure everything out and then said, “right. now we can make it!” The making was the designing. Assumptions and questions are raised. We interrogate our own ideas and create new ones, whilst making and building and handling material and trying out little scenarios. The peculiar nature of the clock was such that we had debates, one in particular was about what the display should do when the little keyfob alarm-buzzer part was removed to be given to a friend. I felt quite strongly that the display on the main clock should go off, so that you’d have to Trust completely the person who was meant to be your human alarm. Otherwise, you can wake up and check the time, which is an implicit way of not really trusting that human alarm person.

This was the bit of fiction insofar as a clock like this would be quite otherworldly. There would be a very different set of assumptions about how relationships work; about what waking up entails and what it is for (getting to a meeting on time; making sure the kids are ready for school; not missing a flight and all the weight and significance of what happens if you *don’t do these things when and what time they need to be done.)

It would be a very different world if we just *woke up when we woke up, rather than waking up to the same time nearly every day. It’s a slightly skewed universe that this clock came from, but it’s crucial to do this kind of design. Why? Well — it advances the realm of possibilities and begins one considering quite directly about creating new, more curious and sensible interaction rituals. It is also a way of advancing design — doing design differently; questioning and challenging assumptions not only of materials and colors and forms and such, which is good. But questioning the actions and rituals and behaviors of the humans, even to the point of something so seemingly absurd as waking up in different ways. This isn’t to say that people will want to wake up to other people knocking on their doors or shaking their pillows, but it forces a number of unexpected considerations and questions and new ideas that plainly wouldn’t come about if one just focused on different colors for clock displays or snooze button styles. Its a kind of advanced design that is able to engage in its topic by throwing out all base assumptions and free-fall a bit into a weird world and then *not allow the usual questions to arise. Sink into the discomfort zone and do some advanced designing.

How does the underpinnings of social relationships become a design principle? How does one design for trust? Can an intangible like trust become embedded in an object?

The principle that “theory” can be expressed in an object plays a part in this question. Substitute “Trust”, a kind of philosophical principle that is perhaps, in my mind, best expressed through exemplars that represent it, rather than the abstractions of philosophical discourse.

The topic of “Trust” presented itself in October 2008 with a tremendous force. The world rattled as global networks of “Trust” institutions collapsed on a scale that sent apcoloyptics scurrying for Old Testament passages consistent with the sequence of events witnessed across the globe. “Trust” became a keyword for these events as macro social institutions that were once “too big to fail” failed despite their size. These institutions that were once the bedrock of society cracked and dissipated and in their failure, revealed what Trust is, at its core. It is, of course – people and the networks of relationships that define what it is to be a social being.

In the Advanced Design studio at Nokia, we were curious about Trust and what it means. Trust is recognized as a core values of the Nokia brand. The worldwide events brought the topic to the fore and provided an impetus for a design-based experiment. Our question was — what is Trust and how could one design with Trust as a guiding principle? How do you embed Trust in the material of a designed object?

The project walked around the topic, building up the studio’s expertise on the topic through the Design equivalent of a “literature review”, both in the sense of readings as well as a more tangible equivalent. We collected essays and books and made things — objects. We brought in both internal to Nokia and external experts on the topic. A social psychologist talked to us about how ordinary people become extraordinary liars. We followed closely the daily events of the macro level systemic failures of insurance companies, banks, economies and entire governments.

Our goals were deceptively simple — to develop a set of principles that could become “actionable” and be “designed-to” in order that Trust could be embedded in the material of an object.

Amongst a dozen principles, one is worth highlighting and is best paraphrased and represented in one of our tangible exemplars. The principle goes something like this: facilitate the trust network — allow people to trust the people they already trust.

Our tangible prototype was, of all things — an alarm clock. We called it the Trust Alarm Clock. The design brief was simply to make an alarm clock that embodied the principle — an alarm clock that highlighted the idea that trust is a relationship between people. At the same time, it was a platform that allowed us to experiment with this simple principle. As you will see, it is an almost absurd object. But it was the response to the brief that we made, without questioning our motivations, but rather following our curiosity on the topic of Trust.

The clock is best described directly. It consists of two components. The main component is not unlike a conventional bedside alarm clock. The second sits nearly where one would expect the canonical “snooze” button of a conventional alarm clock. This second piece is a small, removable “fob”. When one sets the desired time to wake up, the fob is programmed with a digital count down timer. The alarm setting ritual starts when one sets the wake-up time using a dial on the back of the clock. While doing this, the fob timer is configured so that its count down would expire and the fob would “alarm” when the alarm clock setter would like to wake up. The ritual is completed when the fob is removed from the main component and given to a most trusted friend. In that ritual of handing over the fob, the network of trust is established and embodied. The “handshake” of the passing represents the creation, or the invigoration of trust in its most elemental form. Handing over the fob signals that there is Trust amongst this small, two-person social network. If one wants to wake up — or be woken up — one must first consider a number of things. Primarily — who do I trust to wake me up? Who would I want to be woken up by? To whom do I want to convey that I do indeed trust them?

Short animation of an interaction ritual.

We did not suppose that a bedside alarm clock like this has mass-market appeal. It’s a theory object — a way of questioning and probing and exploring the idea of Trust as made into this provocative material exemplar. In a way it is a bit of fiction, only not written, rather made as a physical object that compels one to think of the stories and “user experiences” that may surround it. The fiction is established through a provocation created through design practices.

Theory objects are like material instantiations of ideas — perhaps even our hopes and our imagination. Theory objects refract some social practice in a peculiar and hopefully thought-provoking way. They are “theory objects” in this sense, ways of shaping refining, refracting and altering social practice hopefully in a way that creates more habitable worlds.

The theory object is a way to think about “technology” as something that does more than utilitarian or instrumental. It is an embodiment of some sort of practice that is not outside of the realm of social action. In other words, the theory object is a social object — one that can shape and mutate social practice. Technologies are mutable. They can be what we need them to be, and shape how we experience the world and in that way, are social. What we are doing here is over-emphasizing this point by skirting around the usual assumptions about technology in order to make this point about their social nature more evident and obvious and provocative.

Why should we care enough to make this point that technologies are embodiments of social practice? Because we need to reveal the human hand in their creation and their possibility. Once we can see that people put these things together (and show this process plainly, through images and descriptions without secrets) it becomes possible to talk about how they could be different, or obey different laws and assumptions — possibly become more environmentally conscientious, or help us find playful ways to be more compassionate to mean people, or find ways to be kind to strangers (whatever..need some concrete examples, perhaps anticipating the projects.)

In the case of the Trust Alarm Clock, we were confronted with a rather exciting and unconventional direction for ways of waking up, which everyone does, with the regrettable exceptions, of course. The question evolves beyond *who do I want to wake me up, and who do I trust the most to, say — make sure I get up to make an unusually early meeting or airplane departure. Rather, through this theory object we were drawn into thinking about other *things one may wake up to besides the time of day. What sort of alarm clock might the near future bring that represents a trusted evolution of the waking-up ritual. Perhaps an alarm clock that allows someone in my networked social graph to wake me up. Or — are there things that I trust more than people in these circumstances? Somethings that are beyond the rather mechanistic and mundane ritual of waking to the time, which, after all — is not particularly exciting. Might the things that are more relevant or consistent with our connected age be what wakes us in the near future? In the near future, might we trust more an alarm clock that wakes us up when other people start waking up in order to facilitate that sense of being amongst a larger group of people who are also starting their day. Who are we to say that the now common ritual of waking to a specific time become as antique as luggage without wheels.