Times Square Urban Living Room from Julian Bleecker. More Apparatus Videos.

[[Update: The Apparatus was exhibited at the HABITAR show at LABoral in Gijón Spain this summer 2010.]]

A couple of months ago a colleague, Jan Chipchase, floated by my desk and handed me a book of his called “The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces” by William H. Whyte . I had no idea who this Whyte character was and I could only guess what it was about and, just by the title — I figured this would lead me down another rabbit’s hole of exploration and experimentation.

. I had no idea who this Whyte character was and I could only guess what it was about and, just by the title — I figured this would lead me down another rabbit’s hole of exploration and experimentation.

As I flipped through the pages, looking at the images of urban observations of New York City from the 1970s, I was enthralled by the technique as well as the substance of the material. Whyte and his team were capturing the intriguing, sometimes curious ways in which people adapt small corners of urban space and their habits and practices and rituals. The pace and momentum of pedestrian movement is intriguing. Without assuming anything in particular, Whyte’s work was capturing movement in a seductive way — even small scale jolts and shifts and gestures. Someone moving a chair just a small bit to indicate that he is not attempting to invade someone’s microlocal private space. You see the “fast-movers” bobbing and weaving quickly around a phalanx of slow moving tourists, window shoppers or a more elderly pedestrian.

Wonderful, intriguing stuff. Sold. Hooked. What’s the brief? Oh, what would I do? Follow footsteps and curiosities, I guess. I was curious — how can the momentum and pace and speed (or lack thereof) of the urban flows be captured, highlighted, brought into focus and revealed in such a way as to visually describe time, movement, pace, scales of speed and degrees of slowness?

There is lots to say about Whyte, I am sure. I have only begun to scratch the surface of this well-known urban sociologist, explorer, scout, observer. But, for the purposes here what happened as a result of this brief conversation with Jan was something that spread through the studio — a bout of curiosity that led to another, other project. It started simply by wondering if the observational studies that Whyte had done both in this book and in other projects could be done today? And, if so — what might they observe? What might be the questions? By what principles and assumption would small urban spaces be explored?

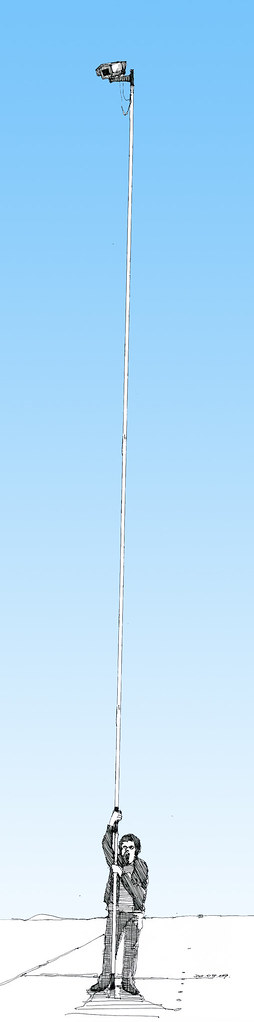

A copy of the films Whyte had made was secured in short order. Simple observations from ground level as well as from carefully chosen vantage points up high, above the ground. This intrigued me. There had been a project in the studio this time last year with things placed high for observational purposes (high chairs, periscopes, etc.) and it was filed away in the “lost projects” binder, so this seemed perhaps a way to revive that thinking. Over the course of a week, I made four trips to Home Depot, Simon jigged a prototype bracket on the CNC machine, and I had a retractable 36 foot pole that I imagined I was going to hang a heavy DSLR off of — it scared the bejeezus out of me and required two people to safely raise up. Too high, too floppy.

Another pole — 24 feet. Daunting but serviceable. It retracts to 8 feet, which is still quite high, but the range made it worth the embarrassment. After a brief bang around the reputation and suggestion networks, a wide field of view camera was identified and two ordered. Two cameras, secured to the pole produced a fair resolution, very wide field of view for displaced observations from a peculiar point of view. Good enough.

Penn Station Still Observation from Julian Bleecker on Vimeo.

Observation apparatus deployed at 7th Avenue main entrance to Pennsylvania Station, NYC, capturing ingress & egress flows, pedestrians waiting, deciding, waking up in the morning upon hitting the sidewalk, &c. The slow-scan mode highlights things which are not moving and therefore often discounted as to their import such as, for instance, the two peculiar characters to the far left who scarcely move (and were still there at the end of the day, around 7pm!), defensible space obstacles in the form of potted plants, people who wait for things, time to pass, people or taxi cabs, &c.

15th Street and 5th Avenue, New York City.

Using some generative algorithms to show neutral zones of flow and highlighting areas of relatively stable inactivity. Somewhat mitigated by the windiness of the day which caused the cameras to move quite a bit.

Whyte was intrigued by the movement, flows, behaviors, but also emphasized the engaged observations — pen and paper, not just measurements and statistics. He was observing and analyzing both statistically — flows of people per time period over various widths of sidewalk, for example — as well capturing those things that one misses in abstracted data sets. In the film, his avuncular tone draws our attention to small curious practices. Things like someone to moving a chair in a public open space barely a few feet from where it was so as to indicate to a nearby fellow New Yorker that they were not intending to impose upon their public-privacy.

There was something about these sorts of couplings between the analytic data — numbers and so forth — and the observed, seen and demonstrated activities of people. Observed practices crafted into a kind of story about this subject — the social life of small urban spaces. Finding ways to observe and perhaps produce useful insights and design inspirations based on the observations seems a reasonable goal. There is only so much you can do with the books of abstracted data squirreled away some place before you have to go out in the world. Where I was most interested in exploring was somewhere “lower” than the high-level observations which produce intriguing visualizations but are many steps removed from the everyday, quotidian practices. Some empirical, rough-around-the-edges, observational data ethnography. A close cousin of the truly fascinating data visualizations we have grown to love. Perhaps close to Fabien’s notion of citizen sensors and citizen cartography.

We got plenty of guff with the Apparatus when we took it on the new Highline Park. One rather abrupt park minder — sort of behaving like an airline stewardess on a really bad day — was not pleased with the pole at all and let us know it. I had to talk to someone back at the offices of the "Friends of The Highline" via a cellphone given to me by a guy who was like a human surveillance entity. The woman on the phone explained – after listening to my perhaps overly analytic and historic description of the project, Whyte, &c. – that they do not allow tripods or, "you know..long poles" in the park.

Errr ahhh…

It was all very weird, and very un-appealing and put a cloud on what is a playful project, I think, but — *shrug*.

It’s all to be figured out. Or not. Perhaps its just observation. Scraps and visual thinking. Some notes in video. Constructed objects and anticipation of going mobile in Seoul and Helsinki and Linz and London. &c. Or some kind of exploration to suggest alternative ways of seeing the world around us. That may be closer to the point, at least now.

The post-processing stages of the activity are mostly explorations of ways in which individuals or small groups of people in movement could become their own producers of representations of what they do, in an aesthetic sense. What other sorts of systems might people-flows evoke or be reminiscent of? Weather patterns? Displacement grids? Where is there stillness in the bustle? Can the city’s flows be slowed down to evoke new considerations and new perspectives of what happens in the small urban spaces?

People themselves are often seen to be controlled in a top down fashion — even less insidious than “the man”, I think of the significant pedestrian operator — the “I want to cross” button at many busy intersections. It’s a point of contact with the city’s system of algorithmic, synchronized flows. But what about people as their own algorithms, by virtue of their occupancy of urban space? Not following specific top-down plans, but bottom up actions and movements. Not augmented reality but productions of realities. The center of what happens, displaced from the operational command center that articulates how the flows will operate.

I love these moments that countervene the system-wide control grids, which you can see if you watch carefully the raw footage from 15th Street and 5th Avenue where pedestrians spread themselves into the street, stretching the boundaries of the safety of the sidewalk in anticipation of the crossing. Or, perhaps something I love less but it is still something to note, a bicyclist turning the corner against traffic, possibly into pedestrians who may be less inclined to look from whence traffic should not be coming.

We push buttons to control the algorithms of the city, as in the buttons to control signals and so forth. Or roll our cars over induction loops – these are parameters to the algoithms of top-down controls over urban flows. Suppose we interceded more directly or suppose the geometry of the city were represented this way, as a product of the non-codified “algorithm” of movements.

What sort of world would this be? What would it look like?

Highlighting only things that are moving in the Union Square Farmers’ Market.

A cartesian grid distorted by flows around the Union Square Farmers Market.

Help thanks to Marcus Bleecker, Chris Woebken, Rhys Newman, Simon James, Jan Chipchase, Aaron Meyers, Noah Keating, Bella Chu, Duncan Burns, Andrew Gartrell, Nikolaj Bestle. And so on.

Videos live online and will accumulate over time. This is Times Square, NYC, Highline in Chelsea NYC, and a generative video done with Max/MSP Jitter