…and apparently available only in the UK presently. John Marshall and I have a manifesto-y essay towards the end of this.

Category: Book Stuff

Digital Blur Book Launch At Architectural Association April 27

This book Digital Blur — in which John Marshall and I have a sort of drunken, double-bandolier-wearing bandito-style essay on *undisciplinarity — will launch on April 27th in London at The Architectural Association Bookshop, which is a fantastic bookshop anyway so you basically can’t loose.

if anyone goes..i wouldn’t mind a photo of the event just to show my mother what i have wrought, in my own humble, minuscule way.

Digital Blur: Creative Practice at the Boundaries of Architecture, Design and Art’

On behalf of Libri Publishing I am delighted to invite you to the launch of Paul Rodgers and Michael Smyth’s new book.

A formal invitation is attached.

The launch is being held on: Tuesday 27 April 18.30 – 20.30

The AA Bookshop

Architectural Association

36 Bedford Square

London

WC1B 3ES

The nearest underground station is Tottenham Court Road.

Wine and soft drinks will be served. We hope you will be able to join us.

Please R.S.V.P. by email to: julie.farmer@libripublishing.co.uk

Continue reading Digital Blur Book Launch At Architectural Association April 27

Undisciplinarity (essay in book)

The book that resulted from the ‘inter_multi_trans_actions: emerging trends in post-disciplinary creative practice’ symposium at Napier University in Edinburgh, Scotland on Thursday 26 June, 2008 is nearing publication.

The book ‘Digital Blur: Creative Practice at the Boundaries of Architecture, Design and Art’ edited by Paul Rodgers and Michael Smyth will now be published by Libri Publishing following Middlesex University’s decision to close Middlesex University Press.

According to Amazon the book is due on 31 March, 2010.

The book contains an essay by John Marshall and myself that is preambled thus:

Marshall and Bleecker, in their essay, propose the term ‘undisciplinary’ for the type of work prevalent in this book. That is, creative practice which straddles ground and relationships between art, architecture, design and technology and where different idioms of distinct and disciplinary practices can be brought together. This is clearly evident in the processes and projects of the practitioners’ work here. Marshall and Bleecker view these kinds of projects and experiences as beyond disciplinary practice resulting in a multitude of disciplines ‘engaging in a pile-up, a knot of jumbled ideas and perspectives.’ To Marshall and Bleecker, ‘undisciplinarity is as much a way of doing work as it is a departure from ways of doing work.’ They claim it is a way of working and an approach to creating and circulating culture that can go its own way, without worrying about working outside of what histories-of-disciplines say is ‘proper’ work. In other words, it is ‘undisciplined’. In this culture of practice, they continue, one cannot be wrong, nor have practice elders tell you how to do what you want to do and this is a good thing because it means new knowledge is created all at once rather than incremental contributions made to a body of existing knowledge. These new ways of working make necessary new practices, new unexpected processes and projects come to be, almost by definition. This is important because we need more playful and habitable worlds that the old forms of knowledge production are ill-equipped to produce. For Marshall and Bleecker, it is an epistemological shift that offers new ways of fixing the problems the old disciplinary and extra-disciplinary practices created in the first place. The creative practitioners contained within the pages of this book clearly meet the ‘undisciplinary’ criteria suggested by Marshall and Bleecker in that they certainly do not need to be told how or what to do; they do not adhere to conventional disciplinary boundaries nor do they pay heed to procedural steps and rules. However, they know what’s good, and what’s bad and they instinctively know what the boundaries are and where the limits of the disciplines lie.

”

(Via Designed Objects.)

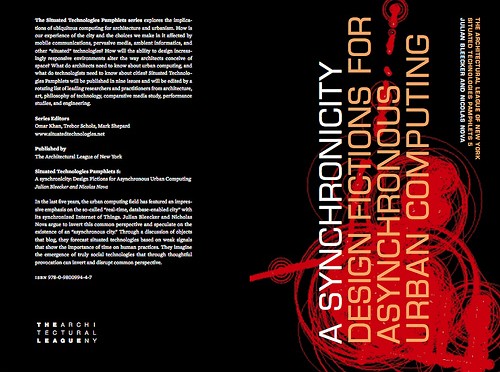

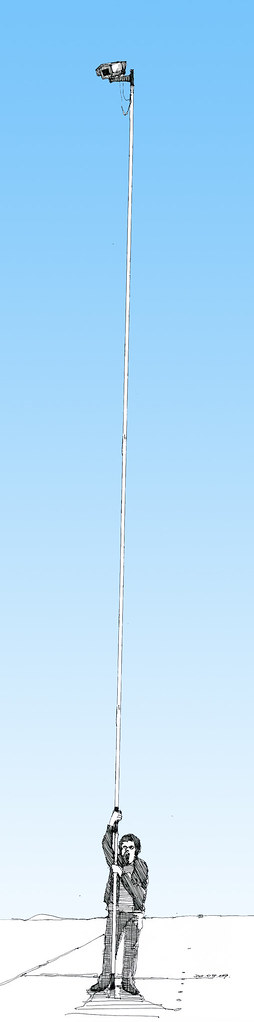

A synchronicity: Design Fictions for Asynchronous Urban Computing

This just in: A Synchronicity: Design Fictions for Asynchronous Urban Computing — Nicolas Nova and myself conversing about what we’re calling asynchronous urban computing — has been released by the Architectural League of New York. It’s a dialogue on an inverted urban computation framework, with material embodiments of the peculiar designed artifacts we cooked up to help explicate our upside down worlds.

Here’s what the editors have to say:

In the last five years, the urban computing field has featured an impressive emphasis on the so-called “real-time, database-enabled city” with its synchronized Internet of Things. In Situated Technologies Pamphlets 5, Julian Bleecker and Nicholas Nova argue to invert this common perspective and speculate on the existence of an “asynchronous city.” Through a discussion of objects that blog, they forecast situated technologies based on weak signals that show the importance of time on human practices. They imagine the emergence of truly social technologies that through thoughtful provocation can invert and disrupt common perspective.

It’s available from Lulu, which means you can download it for free, or buy it for real and augment the reality of your book pile. I suggest buying it. We don’t get a penny, but the folks over at The Architectural League and the Situated Technologies genies need to keep doing the cool, curious things they do.

Thanks to the Situated Technologies editors, Omar Khan, Trebor Scholz and Mark Shepherd.

Digital Blur: Stories from the Edge of Creative Design Practice

Cribbed from John Marshall’s Designed Objects blog, he and I contributed a short, analytic essay on inter/trans/undisciplinarity as it pertains to design practices for this book — Digital Blur: Stories from the Edge of Creative Design Practice. The book is forthcoming in September-ish I am told and contains a collection of conversations and project reviews from some wonderful designers practicing in the edgy, curious, peculiar near future where things are calibrated slightly differently and the world has tipped a little to the side. Can’t wait for this to come out, not so much so I can see what we wrote (I have trouble reading my own writing and I’ve long since forgotten what we said, although I’m sure it is somewhere on the hards drives or clouds) but because these sorts of compilations of projects are great sources of energy and inspiration.

• ISBN: 978 1 904750 69 7

• 264pp

• 264 x 196mm

• £24.95

• Publication date: September 2009

Why do I blog this? Another annotation about forthcoming written things and a busy fall season of exciting activities.

Continue reading Digital Blur: Stories from the Edge of Creative Design Practice

Upcoming essay on the asynchronous city

Via Nicolas — Upcoming piece about the asynchronous city:

Just for the sake of bringing things to the table before they do: Nicolas Nova and myself are putting a final touch to a pamphlet entitled “A synchronicity: design fictions for asynchronous urban computing” in the Situated Technologies series. Here’s the blurb:

“Over the last five years the urban computing field has increasingly emphasized a so-called “real-time, database-enabled city.” Geospatial tracking, location-based services, and visualizations of urban activity tend to focus on the present and the ephemeral. There seems to be a conspicuous “arms” race towards more instantaneity and more temporal proximity between events, people, and places. In Situated Technologies Pamphlets 5, Julian Bleecker and Nicolas Nova invert this common perspective on data-enabled experiences and speculate on the existence of an “asynchronous” city, a place where the database, the wireless signal, the rfid tag, and the geospatial datum are not necessarily the guiding principles of the urban computing dream.“

Due for September 2009. A sort of updated version of near future laboratory thinking that builds upon various projects, discussions (and partly going beyond material from my french book). Stay tuned.

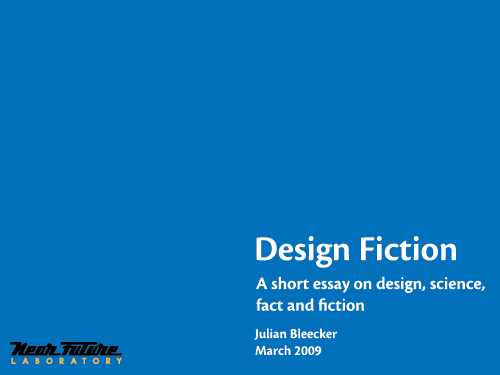

Design Fiction: A Short Essay on Design, Science, Fact and Fiction

A couple of years ago, in a small discussion group while I was teaching at USC, Paul Dourish presented an early draft of a paper he and Genevieve Bell were working on. If you read this blog, you probably know the paper. It’s called ” ‘Resistance is Futile’: Reading Science Fiction Alongside Ubiquitous Computing.” It’s a wonderful paper for a number of reasons. What is most wonderful, for the purposes of this dispatch, is the clever way the paper creates a conceptual linkage through science-fiction-ubiquitous-computing. The idea that “science fiction does not merely anticipate but actively shapes technological futures through its effect on the collective imagination” and “Science fiction visions appear as prototypes for future technological environments” — well..this is really juicy stuff.

(Their paper is generally around in draft form, for better or worse, thanks to the Google. It’s forthcoming in the Journal of Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, which is generally only readily available to academics and researchers with access to pricey journals.)

Paul asked myself and a number of people to consider writing something like a response or further considerations kind of thing that could sit alongside the article’s publication. I started in on this last summer. Ultimately, for reasons that became clear as I was writing the essay, I decided that there would be more to be said than would be tolerated in a staid, expensive, peer-reviewed academic journal, never mind that there could possibly be a wider conversation beyond the ubicomp community as my thinking ran into film, design, fan culture and unanticipated other places.

The short bit I wrote ended up as “Design Fiction: A Short Essay on Design, Science, Fact and Fiction.” It’s available as a downloadable PDF, out there in the on The Near Future Laboratory’s modest puff of Internet Cloud. (Its various incarnations as slideshows and talks can be found here on Slideshare.)

What is this all about?

Extending this idea that science fiction is implicated in the production of things like science fact, I wanted to think about how this happens, so that I could figure out the principles and pragmatics of doing design, making things that create different sorts of near future worlds. So, this is a bit of a think-piece, with examples and some insights that provide a few conclusions about why this is important as well as how it gets done. How do you entangle design, science, fact and fiction in order to create this practice called “design fiction” that, hopefully, provides different, undisciplined ways of envisioning new kinds of environments, artifacts and practices.

I don’t mean this to be one of those silly “proprietary practices” things that design agencies are fond of patenting. This is much more aspirational than that sort of nonsense. It’s part an ongoing explanation of why The Near Future Laboratory does such peculiar things, and why we emphasize the near future. The essay is a way of describing why alternative futures that are about people and their practices are way more interesting here than profit and feature sets. It’s a way to invest some attention on what can be done rather immediately to mitigate a complete systems failure; and part an investment in creating playful, peculiar, sideways-looking things that have no truck with the up-and-to-the-right kind of futures. Things can be otherwise; different from the slipshod sorts of futures that economists, accountants and engineers assume always are faster, smaller, cheaper and with two more features bandied about on advertising glossies and spec sheet.

Design Fiction is making things that tell stories. It’s like science-fiction in that the stories bring into focus certain matters-of-concern, such as how life is lived, questioning how technology is used and its implications, speculating bout the course of events; all of the unique abilities of science-fiction to incite imagination-filling conversations about alternative futures. It’s about reading P.K. Dick as a systems administrator, or Bruce Sterling as a software design manual. It’s meant to encourage truly undisciplined approaches to making and circulating culture by ignoring disciplines that have invested so much in erecting boundaries between pragmatics and imagination.

AIAA Houston Section newsletter, April 2008.

When you trace the knots that link science, fact and fiction you see the fascinating crosstalk between and amongst ideas and their materialization. In the tracing you see the simultaneous knowledge-making activities, speculating and pondering and realizing that things are made only by force of the imagination. In the midst of the tangle, one begins to see that fact and fiction are productively indistinguishable.

Design is about the future in a way similar to science fiction. It probes imaginatively and materializes ideas, the way science fiction materializes ideas, oftentimes through stories. What are the ways that all of these things — these canonical ways of making and remaking and imagining the world — can come together in a productive way, without hiding the details and without worrying about the nonsense of strict disciplinary boundaries?

I’ve written more about this, from some conversations with friends and colleagues last fall. It’s here, in this PDF called “Design Fiction: A short essay on design, science, fact and fiction.” It started at that discussion group with Paul in 2005 or 2006, and evolved into something I presented last fall at the Design Engaged ’08 workshop in Montreal, then the SHiFT 08 conference in Lisbon last October, then at the Moving Movie Industry conference, finally at the O’Reilly ETech 2009 conference.

Subsequently, this topic has been taken up in a variety of forms and venues. Bruce Sterling has a wonderful essay on the topic in the ACM Interactions journal. And I organized a panel at South by Southwest 2010. with Bruce, Sascha Pohflepp, Stuart Candy and Jake Dunagen with Jennifer Leonard doing an excellent job of wrangling and moderating. (The video should be available in a month or so from mid-March 2010.)

By request, here is a Design Fiction Printable Edition that will print on normal, human paper, to scale on 8.5×11.

Why do I blog this? A written kind of design provocation. For the last several months, there’s been a bit more word cobbling than wire soldering. The two practices contribute to the same set of objectives, which is to make and remake the world around us, provide new perspectives and evolve a set of principles that help make the making more imaginative, more aspirational.

I should also add that, when I was writing my master’s thesis on Virtual Reality some time ago (it’d have to be ‘some time ago’ for that topic), I wrote about science fiction meeting science fact, which was some of the earliest inspiration for this work, shared by the laboratory imaginary of the grad student “cyberfreaks” in the University of Washington HITLab and our reading/re-reading of Gibson’s Neuromancer during the early 1990s. Not just Neuromancer but all kinds of science fact/fiction. The simultaneity of the science fiction and the military science fact that was the first Gulf War. I wrote about that, too, because I was being taught by the guy who made that military technology, which was an unpleasant experience, but one from which I learned a great deal about how fact and fiction can swap properties. That same curiosity led to further interest in visual stories and their role in understanding and making sense of the world around us, especially in science fiction film and video games. I wrote a dissertation on this, studying with Donna Haraway, err..when I was a young lad in 1993-95. Therein was a chapter on Jurassic Park as simultaneously science fact and fiction. We had plenty of lively discussions specifically on this film. (Sarah Franklin was visiting at UCSC then and wrote some really amazing stuff about science fiction and genetics out of that, back in the late 90s that appears in “Global Nature, Global Culture.”) There was a seminar paper I did on “Until the End of the World”, looking at the Sony Design concepts Wim Wenders used to create a compelling science fact within the science fiction diegesis. In there was one of the earliest bits of video game commentary (SimCity 2000) from a critical theory perspective, not that I care about ordinality, but some folks seem to. There was a chapter on the SGI Reality Engine, ILM and Special Effects in science fiction (mostly Jurassic Park, which brought me to David Kirby’s early work – he’s the guy who coined this phrase ‘diegetic prototypes’, btw) and science fact showing the techniques and technologies that allow media to cross from fiction to fact. And so on. In many ways, this essay is a continuation of these interests and one I share with a great deal of friends, colleagues and complete strangers, I’m sure. Lots of people are playing around in here, excitedly and eagerly swapping ideas and stories. It’s a conversation that’s usually quite energetic and fun. If the ideas herein intersect and entangle with yours, it means you’re a healthy, creative individual, aspiring for a better near future we all hope to one day to live within. It’s a waste of my time to say things like — yes, I’m working on that. Yes, I have been working on this while you were in grammar school. And to do this every time someone mentions something you are also thinking on? That’s just preposterous. I used to do that with students, or point out to them someone who has also been working on something they think they have thought about for the first time. Inevitably, for the younger students who think they’re the only ones in the world who thought about such-and-so idea — they shrink and pout and get petty and don’t realize that they are in a world of ideas and their uniqueness is in the doing, not the clamoring to be Sir Edmund Hillary climbing that hill for the first time. That’s an ancient, sick model of intellectual and creative cultural production. It’s a world of circulation these days, with knots and rhizomes and linkages between lots of activities.

And that’s all I have to say about that.

Practice Observed: Secure Improvisations

Improvisation enacted to overcome a secured door that is probably the most often used in the studio, sitting near to the kitchen and coffee machines (and the sadly defunct espresso machine..) A stapler used to keep a door open helps one poor sould evades the secure RFID lock. Likely, their secure card was left on their desk or some such and the stapler provides them a momentary work-around to returning to their desk, retrieving the card and then getting back to the necessary business of fueling up on the morning caffeine.

Why do I blog this? Observing small but actions, especially around improvisation. I am curious about the way objects become practice-based activations and serve as beacons and indications of evolving materials and materialized social practices. All this and the entanglements within the many layers (morning rituals, security, barriers, identification, access, RFID, office supplies, etc.) and the entanglements amongst humans and non-human hybrids.

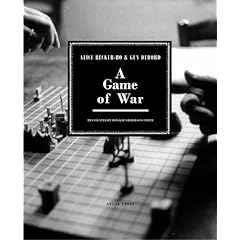

Alex Galloway's "Kriegspiel"

Alex Galloway came by to do a short talk discussing his new game “Kriegspiel” based on Guy Debord’s “The Game of War” This is a curious strategy game that Debord created while in the midst of a bit of a creative flat-spin. It was created in an artisinal mode, with 5 hand crafted editions constructed with a collaborator. Evidently one of the sets — made with metal pieces — was recently on display in NYC on loan from Debord’s widow. Galloway has some interesting archival style insights into the historical context of the game’s development and Debord as a cultural figure of some importance, and I recommend finding whatever he has written on the topic. (It seemed as though he was reading from working-notes for a longer bit of work on this.)

What I find most interesting in this context is the articulation that Galloway has performed between historical archival work and the expression of these “findings” through this game. The game is, by Galloway’s own description, based entirely on the original rules of Debord’s game design. Alex describes himself as fascinated by games, but not at all a game designer. Thus, finding a cultural hero of academics and scholars world-wide who also happens to have designed a game makes for an excellent scholarly project. It skirts the boundary between an activity some critical scholars might poo-poo (game design) and an activity the most conservative scholars could at least chomp on (a proper archival inquiry into the life, history and ideology of a curious figure of some importance.)

Once (and quite a bit “still”) a critical scholar might excavate material from “the archives” (dusty library basements, personal notes moldering in a widow’s attic, interviews with aging contemporaries of the subject, etc.) and then construct a series of insights and anecdotes based on those findings, find a publisher and then stitch together a book on the matter. What Galloway is doing is expressing these insights and anecdotes into a hybrid expression of his findings — a digital, networked game as well as more traditional scholarly essays on the topic. This is significant and important for all the reasons I state over and over here. It’s no longer a viable means for scholarly inquiry to create and circulate ideas and culture solely through dusty old forms like ink on paper. This is a hybrid forms that express both a theory (in this case, Debord’s projection of what strategy is in a rhizomatic, networked era, even though it was constructed many decades before the internet) as well as providing a point-of-entry for someone who has never had a reason to look into this Guy Debord character. For that, Alex’s work is super important.

Parenthetically, I first met Alex back around 2000 when he was doing a residency at Eyebeam (an art-technology center in New York City) while I was preparing to do my residency there. He was working on Carnivore, another important “theory object” instance. I learned a lot about what it was to construct engineering objects that wore culture on their sleeves quite noticeably. It was then that I started understanding how this important hyphenated form called art-technology could offer an opportunity to create and learn about ways to create technological instruments that were more properly and obviously “culture.” Whereas that is always the case — that technology is not outside of culture — it is often hard to find frameworks and communities and mechanisms that allow one to experiment with the mixture. The goals therein are to understand that technology, as culture, is “made” and not “given.” As such, it can be done “otherwise” and need not be the mass-manufactured, extant forms we have today. It can be hand-made properly, even hand-made and massively multiple, but with new entirely preposterous forms that create new ways of seeing, understanding and being in the world.

Alex alluded to some legal hassles with creating the game — a cease-and-desist notice from Dubord’s widow. Liz Losh describes this further in her post on Kriegspiel that she wrote after Alex visited UC Irvine the day after he was at USC.

Unfortunately, as Galloway explained to the audience, he had recently received a lawyer’s letter regarding possible infringement of the rightful owner’s intellectual property. Despite Galloway’s insistence that an “idea for a game” or its “rules” are “not subject to copyright,” those pursuing cease-and-desist orders against the makers of the Scrabulous application for Facebook might disagree.

This point is intriguing for me, particularly in the context of, broadly “fair use” in an academic context. I see this game, generously, as a kind of analytic conversation and engagement with the material. Taking the instructions of the game and creating an “object” that is the game, but in this different, networked, screen-based instantiation is seen by the widow and her lawyers as not at all like writing a paper-and-words-based essay, which is what academics more traditionally do. Here are instances where analytic engagement and the materialization of Alex’s insights and thoughts crosses some boundary into the realm of “unfair” use.

Some parenthetical notes. As I mentioned, Alex and the R-S-G make their own theory objects, as I would call them. Here, with Kriegspiel, they’re using the Java Monkey Engine. — "A 3D game engine written in and for Java. Many features including collisions, particle systems, shaders, terrain system, renderer abstraction."

Technologies of Kindness and Cruelty

Ack. This is one that drives me a little batty. Technology — friend or foe? Well, neither, of course. It’s how the technology is used that determines its normative dimensions. Right?

Pfft.

Even in the world of clever, insightful, creative art-technology, you get practitioners saying things like this about RFID.

I’m not any more optimistic or worried about RFID than any other technology out there. Humans are capable of great kindness and cruelty. That is independent of any technology.

(From Regine’s interview with Doria Fan about her quite nice RFID-based objects. The full interview is here: http://www.we-make-money-not-art.com/archives/2008/03/rfid-workshop-at-imal-in.php)

Why are such binaries even erected? They end up diminishing the fact that “technology” is a human endeavor always. It is no more independent of “humans” or social practice than anything else in the world that gets given meaning in our own terms. Is it just a technology without any human participation? Did it just up an appear in the world like an anonymous fart in the wind? Can you really be no more optimisitic or worried than anything that actually moved you to create? C’mon..get a hold of yourself.

Run the list. Nature? Did it just appear? Nothing that pre-exists us, despite what the atavists would like to believe. It’s entirely constituted and given meaning through our construction of knowledge about it (“science”); through the desire to relate, offset, contrast, etc. ourselves and our lives to it (“things would be better/worse if we ‘returned’ to nature”). And so on.

One consequence of believing that technology is independent of human social practice is that you loose track of the story about who is creating these things, for what purpose and with what consequence to their ability to shape and remake the world. If you don’t tell that story, you have not done your work. You don’t share credit with who is effectively your collaborators. You can no longer ignore their influence on your work than you could ignore the way your peers and mentors shape and make what you do possible. The story does not need to be an indictment, but it is a story without which the work done would not be possible.

Another consequences of believing that technology is independent of human social practice is that you loose your seat at the design table. You end up waiting for someone else (or some weird, independent machine that contains no humans, no beliefs, no ideologies and no selfish or selfless aspirations) to create things that you’ll then complain about, or accept blindly or love.

Technology? How can it be seen as something independent of the practice of humans? Did, say, RFID drop out of the sky one day? No. A bunch of very smart people got together and starting fussing with an idea they had. And they materialized it. They enrolled a bounty of powerful players in various industries and political lobbies and so forth to make it bigger than life. They talked to lots of people in manufacturing to try and figure out how to make millions and millions of various kinds of RFID tags, and detectors. They worked through standards for construction and allocation of identification codes, etc. People wrote books — technical books, trade books, warning books, instructional books.

How is this independent of human capabilities to do great kindness or great cruelty?

The greatest possible damage that can be done vis-a-vis technology and making more habitable, sustainable worlds is to imagine that technology is independent of human capabilities to do good or bad things. To say that technologies are value neutral and then say that it is how we use that particular technology misses the strongest possible case for justifying the occasionally provocative linking of art with technology. That is, to show how our things can be other than they are.

To disrupt the assumption that technologies are not made from often complex social-political-ideological-financial assemblages of the human kind. They may seem “trans-human” — as in a complex web of ideas, politics, money, far-flung manufacturing empires, overwhelmingly enormous projects, powerful financial enterprises all out of proportion to individual humans. But you cannot ever trace this without finding individual humans. Whether the gal on the factory floor hand-assembling some part that machines cannot. Or a venture capitalist in his fancy Freedom chair deciding whether it’ll be go or no-go for a new endeavor. These decisions and practices and hand-work are done for reasons and reasons are backed by normative assessments — what is this “thing” good for?

The disruptor — the art-technology creative, sometimes — is able to untangle what has been knotted together into a specific purpose. Perhaps we should call this person the denoer. The person who untangles knotty assemblages. It can be easier or hard to do the unknotting. Look at the edges and the fraying end-points, like this Google Advertisement. It shows pretty clearly who is participating and for what reason.

This is why “we” lobby for open instrumentalities, open-source, open-APIs, legible toolkits/communities. It’s so that the knot of influences that shape devices for particular purposes can be re-tied to say something else. And this process is much more about retying, about constituting a specific and perhaps different assemblage that is constituted based on a different set of normative goals.

But, the technology was never independent. RFID didn’t just grow from the ground. When you believe that, you loose the deep, human influences and political complexities that are latent within such things. You also loose track of all the problematic implications of new materialized ideas. You give up the possibility of changing or influencing what empires of human will do in fact create such things as RFID, and influencing them in a normative way — that is, influencing them to make things that do not scare you.

Art-technology is not only for the gallery. In fact, the gallery is no more than the first step in the influence creative practices should have in the endeavor of creating new feature sets for the worlds we occupy. Galleries are like Class 1 clean rooms for new ideas. These ideas should materialize in more rugged, designed form that purposely leak out into the world. Shame on the creative technologist who assumes their end-goal should be a gallery show. They should be aspiring to shape their ideas into something that influences or even creates a new enterprise that turns their ideas into world-changing/world-shaping designs that shape and influence and create more habitable, playful, sustainable worlds. Otherwise, it’s all empty ego.

Don’t ever fool yourself into thinking that technology is not synonymous and deeply, inextricably imbricated with the social practice. Ever. You give up everything.

Continue reading Technologies of Kindness and Cruelty